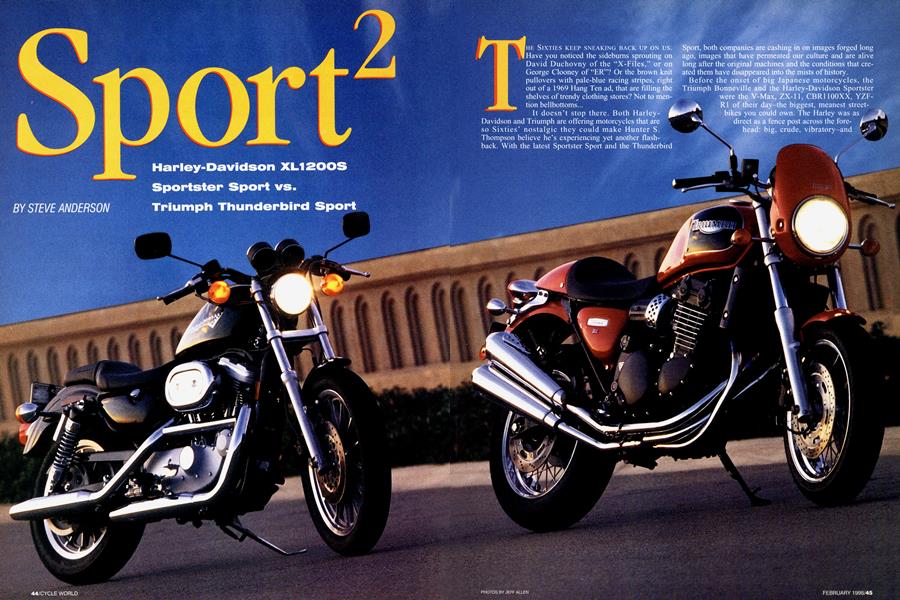

Sport2

Harley-Davidson XL1200S Sportster Sport vs. Triumph Thunderbird Sport

STEVE ANDERSON

THE SIXTIES KEEP SNEAKING BACK UP ON US. Have you noticed the sideburns sprouting on David Duchovny of the “X-Files,” or on George Clooney of “ER”? Or the brown knit pullovers with pale-blue racing stripes, right out of a 1969 Hang Ten ad, that are filling the shelves of trendy clothing stores? Not to mention bellbottoms...

It doesn’t stop there. Both Harley-Davidson and Triumph are offering motorcycles that are so Sixties’ nostalgic they could make Hunter S. Thompson believe he’s experiencing yet another flashback. With the latest Sportster Sport and the Thunderbird Sport, both companies are cashing in on images forged long ago, images that have permeated our culture and are alive long after the original machines and the conditions that created them have disappeared into the mists of history.

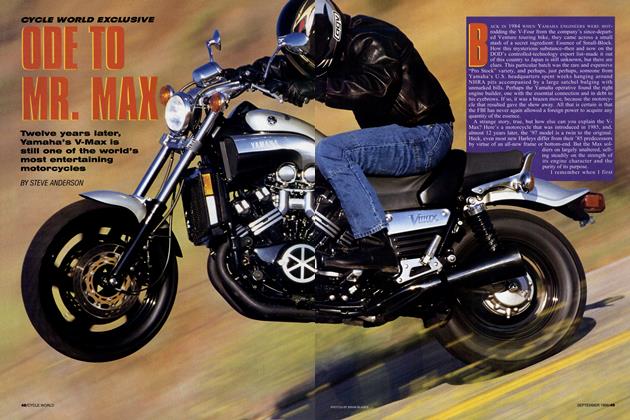

Before the onset of big Japanese motorcycles, the Triumph Bonneville and the Harley-Davidson Sportster were the V-Max, ZX-11, CBR1100XX, YZFRl of their day-the biggest, meanest streetbikes you could own. The Harley was as direct as a fence post across the forehead: big, crude, vibratory-and fast. The carburetors and ignition systems of the era were a sad joke, and there were design problems galore with the old iron-barrel Sportster-perhaps the hottest-running motorcycle ever built-but it made up for it with cubic inches. At a time when a “big” Honda measured 305cc, the 883cc Harley ruled the dragstrip. These days, when you can buy a 1500cc cruiser or a six-cylinder Gold Wing or an over-600-pound BMW “sportbike,” it’s hard to appreciate just how big a Sportster seemed in those days. But in the minds of many Sixties’ motorcyclists, the 500-pound Sportster was pushing-maybe even exceeding-the limits of size for something with sporting intentions.

Certainly, many of them were choosing a Bonneville, the best-selling Triumph of its time. The twin-carb parallelTwin was a lightweight compared to a Sportster, though it towered over Japanese machinery. Compared to a Sportster, it accelerated slightly slower, went faster on top, vibrated somewhat less and handled better. For many riders, it was the sophisticated import that defined balanced high performance.

s Now, three decades later, a sporty Sportster, the XL1200S, again meets a Sixties-style Triumph, the 900 Thunderbird Sport. But, oh, how much has changed! Our bright-red Thunderbird, for one thing, now is the bigger bike, even equipped with the lower-than-stock solo seat (and flyscreen) from Triumph’s accessory catalog. That seat still towers 31.5 inches above the ground, and the bike scales fully 513 pounds dry. It carries those pounds high, too, and you don’t have to lean it over very far in the garage before you think that this would be an easy bike to drop. The Harley, in contrast, has shrunk over the years, its seat height falling to 29.0 inches as the formerly flat seat has snugged up against the frame rails, just like individual customizers were doing 30 years ago. And the Sportster’s 508-pound dry weight has held fairly steady, with lighter aluminum cylinder heads and barrels making up for additions elsewhere, and the low placement of that weight disguising it otherwise. But more than anything else, all other motorcycles have grown to the point that the Sportster seems marvelously compact and, well, almost tiny for a 1200.

And that leads to the other big difference. For better and worse, the Sportster continues in an unbroken, evolutionary line that can be traced back more than 40 years, one produced by a motorcycle company with 95 years of continuous operation. In contrast, John Bloor’s late-Eighties start-up, Triumph Motorcycles Limited, connects to the classic BSA-Triumph works mainly in the ownership of a few trademarks and in similar logo styling. All of its motorcycles have roots that reach back less than a decade, and owe more to Japanese engine design than classic British.

The history shows as soon as you start either bike. Push the button on the Harley, and the starter engages with a characteristic “clunk,” working hard to get big flywheels spinning. When the cold engine lights-particularly if you’re just priming it with the accelerator pumps by twisting the throttle and not using the choke-the cylinders fire sporadically. You can feel each power impulse, the engine speeding up and slowing down, and then catching again. For the Triumph, there’s no starting it without pulling on the enrichening lever; then, the Triple will quickly whir to a quick-revving life familiar to any owner of a Japanese Four, and a world removed from classic Triumph Twins-which weren’t even equipped with electric starters.

Over the years, Harley has thoroughly overhauled the Sportster, with the Evolution redesign in the Eighties giving it new aluminum heads and barrels, and the addition of a fifth transmission gear a few years later providing an excuse to completely overhaul the bottom end. While the current engine is superficially similar to its Sixties ancestors, it actually shares few parts.

This year, the XL1200S gets further modifications in what the factory describes as the “hot-rod” version. The engineers have added cylinder heads with the better-flowing ports and tighter combustion chambers of the 1996-97 Buell SI Lightning, along with new camshafts. The cams were designed to enhance low-speed torque, and created so much cranking pressure with the 10.0:1 compression ratio that a second plug was added to each head to speed combustion and reduce the chances of detonation. In conjunction with a mapped ignition system that varies the spark with both engine speed and manifold pressure, the “coffee-can-fullof-bolts” death rattle that was common with older Sportsters on hot days largely has been conquered-as long as you run premium gas.

The changes haven’t exactly created a hot-rod, but they have produced the best-running stock Sportster ever. The new, short-duration cams create a more stable idle once the engine is warm; it just ticks over at 900 to 1000 rpm with metronomic regularity, without the characteristic Harley lope and misfires. It pulls hard from 1500 rpm, even in top gear, and reaches its 68-foot-pound torque peak at a low, 3500 rpm. By the time it hits its power peak of 56 horsepower at 5000 rpm, the fun is almost over; 500 rpm later, and you’re bumping the rev-limiter. This is motorcycle engine as tractor-heavily flywheeled, slightly slow to respond, but never abrupt and never without torque at normal riding speeds. All it asks is that you put it in top gear and go.

The T-bird powerplant is a world apart. The liquid-cooled, dohc, four-valve-per-cylinder inline-Triple has been enhanced itself for ’98, with the addition of new Keihin carburetors and a 3-into-2 exhaust boosting top end, while mild cams maintain bottom end. The result is a powerband of phenomenal breadth, and one as flat as a frozen lake. Torque peaks at 52.4 foot-pounds at just 3000 rpm, and stays above 50 foot-pounds until 7000 rpm; the power peak of 72 bhp is reached at 8000 rpm. On the road, the feel is that of a quickrevving, modern, multi-cylinder motorcycle with smooth power everywhere in the rev-range. Drawbacks? Well, if it weren’t for the distinctive three-cylinder exhaust note, the feel would be almost four-cylinder characterless.

Of course, sometimes character can be purchased at too high a price. With all the redesigns to the Sportster, Harley has yet to fit it with an engine balancer or rubber enginemounts. At low speeds, that means a pleasant rumble reaches the rider through the handgrips and seat. Above 3500 rpm, though, there’s little pleasure in hanging on; by then, the grips buzz as if plugged into a 220-volt outlet. In top gear, the pleasure/pain transition is clearly defined; anything below 60 mph is wonderful, defined by a torquey feel, an engaging rumble, a tight, slop-free driveline and enough flywheel that the bike doesn’t pitch with every throttle movement. From 60 to about 67 mph vibration grows, finally becoming uncomfortable at the higher number; and by 75 mph, you have to be numb to enjoy the Sportster. The counterbalanced T-bird, in contrast, is smooth everyplace.

Both T-bird and Sportster recently have been blessed with higher-quality Showa suspension, and it shows. Both are the best-riding and best-handling of their line to date. Both take bumps in stride, with notably better compliance than earlier models. Beyond that, the feel is completely different. The Sportster comes with raked-out suspension geometry and a 19inch bias-ply Dunlop front tire; at low speed, its 4.6 inches of trail make the front want to flop into turns, while at high speeds the big tire and conservative geometry make for a very stable motorcycle. Yet the wide handlebar allows you to turn it quickly; it’s a machine that won’t intimidate riders of any skill level. The Triumph, on the other hand, runs a 17-inch Avon radial front tire and less trail; it steers precisely at parking-lot speeds, but wants to fall into comers at higher velocities, wanting to be either upright or fully banked in, and not particularly caring for timidity in the transition between. Expert riders easily will be able to compensate, dialing in a little opposite steering torque to hold their intended line, but the falling-in feeling may unnerve some of the less-experienced riders this retromachine will attract. Too bad, because it has the grip and the ground clearance to make short work of twisty roads.

Brakes also highlight a generational gap between the two machines. The high-leverage Nissin two-piston front brakes of the Triumph are fully in the sportbike mainstream, requiring only a two-finger squeeze on the lever to have the tire squirming and yowling. The Sportster, however, is on the leading edge of Harley design, which means that its Hayes single-piston front brakes are either: (a) extremely, almost dangerously powerful, if you’re a long-time Harley rider; or (b) hopelessly weak, and requiring a death grip to operate, if you’re used to something else. During brake tests, our rider barely could squeeze the Harley’s brake lever hard enough to lock the front tire using his normal two-finger technique, though he still managed a best stop from 60 mph of 125 feet; the Triumph did slightly better at 120 feet from the same speed, and also had less variation from best to worst run.

But, realistically, the styling of the T-bird and Sporty may matter more to their respective marketplace successes than any functional distinctions. In that regard, the $8395 Harley is the unqualified success, stirring thumbs-ups from both enthusiasts and non-riders. The $8795 T-bird drew more mixed reactions, with long-time riders and form-follows-function purists almost offended by its pastiche of not-quite-right Sixties styling elements, while others thought it was one of the best-looking motorcycles they had seen. That reaction is similar to that elicited by certain Japanese cruisers-riders whose eyes have long been trained in classic American styling think these bikes are cartoons, while others think they’re wonderful. We suspect that the Triumph, with its curious styling elements such as fake polished-and-perforated air-filter cover and grotesquely chromed horn, will never pass the Peter Egan Garage Test, but will make many riders happy anyway.

In the end, these bikes are about the way they make you feel because of their appearance, their associations and, yes, their performance. The Harley comes from an unbroken line, created by people who know what a Sportster looks like and is, and make it more so every year. The Triumph is something else, a modem retro-design that bears the same relationship to its historic namesakes as does a Mazda Miata to an MGB. The Sportster is history polished; the Triumph history dreamed. If one appeals to you over the other, there is no wrong decision.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue