Rivalry Revived

The Sporty vs. Trumpet Chronicles

BACK IN THE DARK DAYS JUST AFTER WORLD WAR II, when food and fuel were still rationed in England, one bright spot in the otherwise gloomy picture was motorcycle exports. The Triumph Speed Twin was a breath of fresh air to many Americans, a light, powerful and handy motorcycle quite unlike the Harley and Indian behemoths they were accustomed to. Even so, at 500cc the Triumph eventually had to scramble to stay competitive. Britain needed a bigger machine. The answer was the 650cc Thunderbird, a redesign of the 500 released in 1949, and perennially popular thereafter. Even its Indian-derived name indicated the bike was U.S.-bound. This pumped-up machine returned the advantage to Triumph.

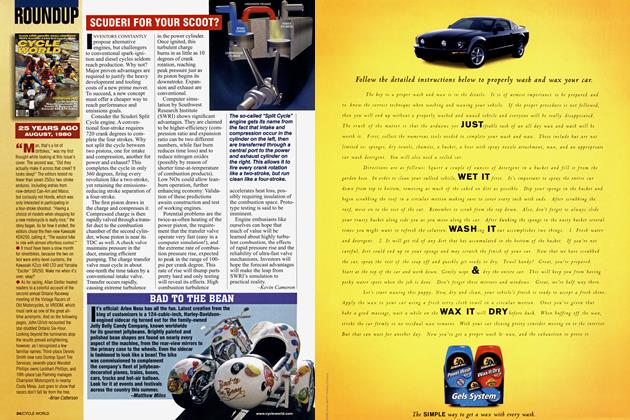

Seeing an alarming flight of riders to foreign machines, Harley, in the fullness of time, and with all deliberate speed, prepared its reply. Although the Motor Company had long known the advantages of overhead valves, and after 1937 had included them in the design of its Big Twins, the only Harleys in production that could remotely be considered light and sporty were the unit-construction K-model flatheads. Because the K was no match for the Thunderbird, it was decided to confer power-boosting ohv (and 10 extra cubic inches for good measure) upon it, and the result was the 883cc Sportster, released in 1957. Triumph replied with twin carburetors and, capitalizing on recent land-speed successes, a new name: Bonneville.

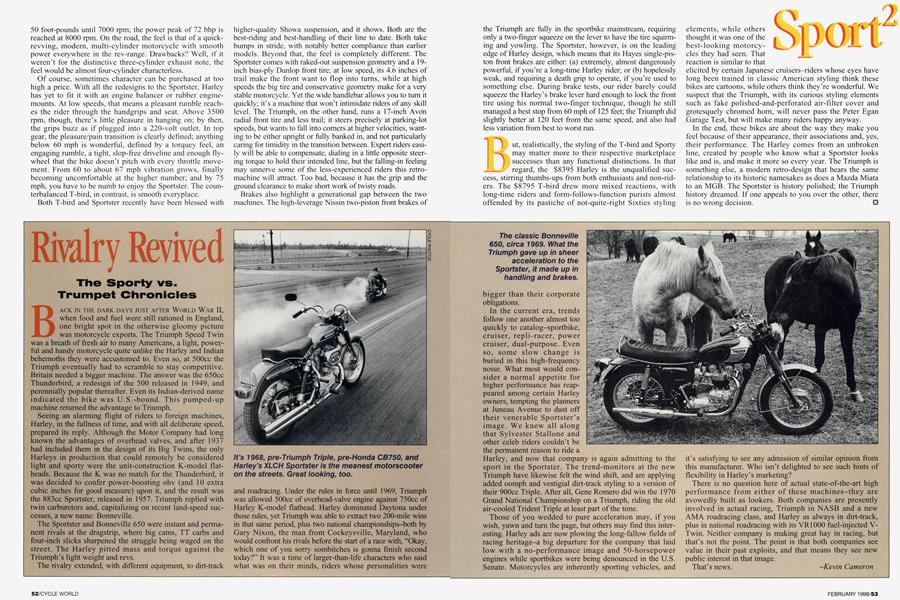

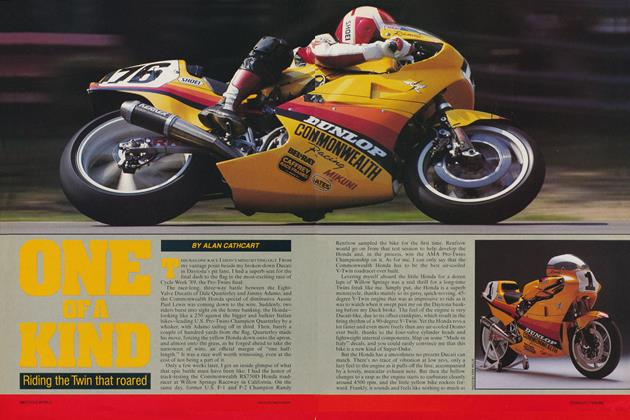

The Sportster and Bonneville 650 were instant and permanent rivals at the dragstrip, where big cams, TT carbs and four-inch slicks sharpened the struggle being waged on the street. The Harley pitted mass and torque against the Triumph’s light weight and revs.

The rivalry extended, with different equipment, to dirt-track and roadracing. Under the rules in force until 1969, Triumph was allowed 500cc of overhead-valve engine against 750cc of Harley K-model flathead. Harley dominated Daytona under those rules, yet Triumph was able to extract two 200-mile wins in that same period, plus two national championships-both by Gary Nixon, the man from Cockeysville, Maryland, who would confront his rivals before the start of a race with, “Okay, which one of you sorry sombitches is gonna finish second today?” It was a time of larger-than-life characters who said what was on their minds, riders whose personalities were bigger than their corporate obligations.

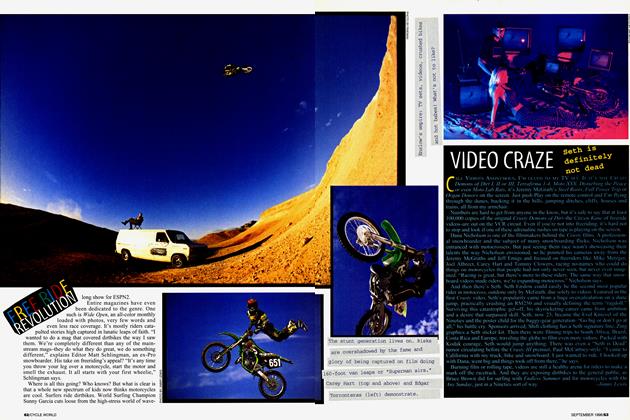

In the current era, trends follow one another almost too quickly to catalog-sportbike, cruiser, repli-racer, power cruiser, dual-purpose. Even so, some slow change is buried in this high-frequency noise. What most would consider a normal appetite for higher performance has reappeared among certain Harley owners, tempting the planners at Juneau Avenue to dust off their venerable Sportster’s image. We knew all along that Sylvester Stallone and other celeb riders couldn’t be the permanent reason to ride a Harley, and now that company is again admitting to the sport in the Sportster. The trend-monitors at the new Triumph have likewise felt the wind shift, and are applying added oomph and vestigial dirt-track styling to a version of their 900cc Triple. After all, Gene Romero did win the 1970 Grand National Championship on a Triumph, riding the old air-cooled Trident Triple at least part of the time.

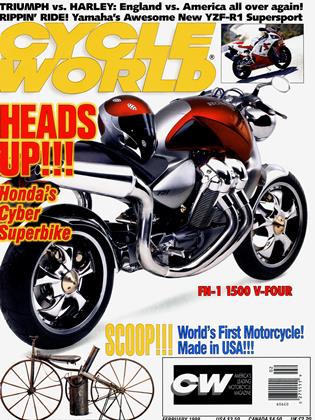

Those of you wedded to pure acceleration may, if you wish, yawn and turn the page, but others may find this interesting. Harley ads are now plowing the long-fallow fields of racing heritage-a big departure for the company that laid low with a no-performance image and 50-horsepower engines while sportbikes were being denounced in the U.S. Senate. Motorcycles are inherently sporting vehicles, and it’s satisfying to see any admission of similar opinion from this manufacturer. Who isn’t delighted to see such hints of flexibility in Harley’s marketing?

There is no question here of actual state-of-the-art high performance from either of these machines-they are avowedly built as lookers. Both companies are presently involved in actual racing, Triumph in NASB and a new AMA roadracing class, and Harley as always in dirt-track, plus in national roadracing with its VR1000 fuel-injected VTwin. Neither company is making great hay in racing, but that’s not the point. The point is that both companies see value in their past exploits, and that means they see new public interest in that image.

That’s news.

Kevin Cameron

View Full Issue

View Full Issue