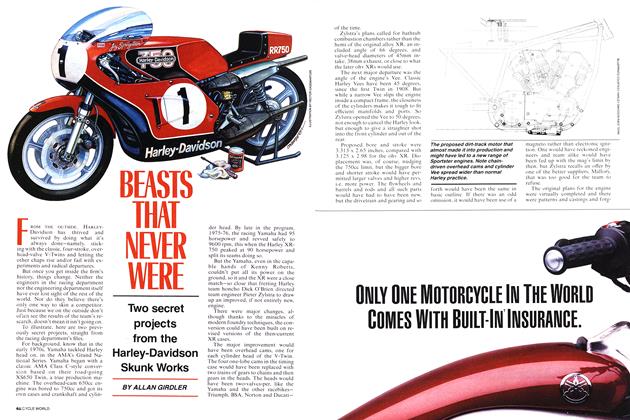

FULL RACE

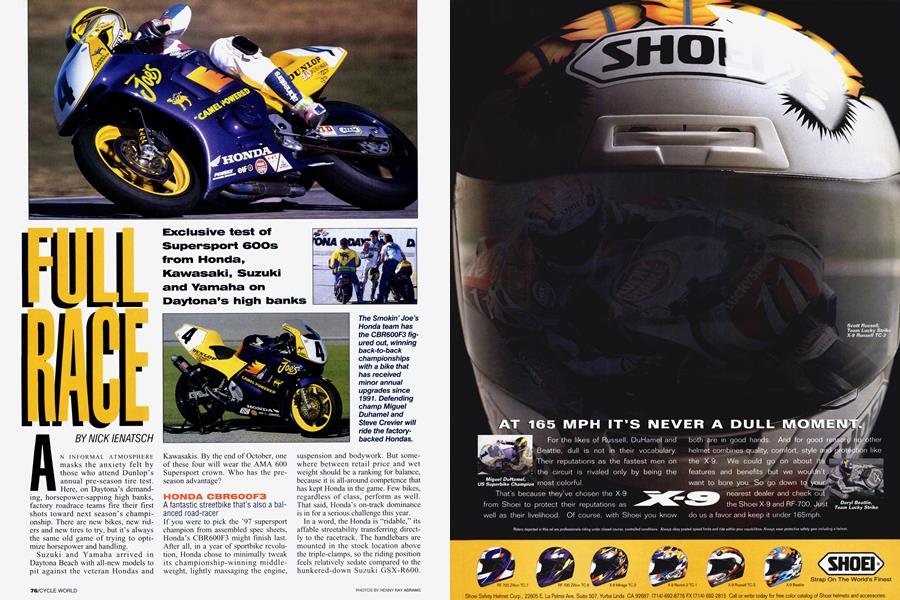

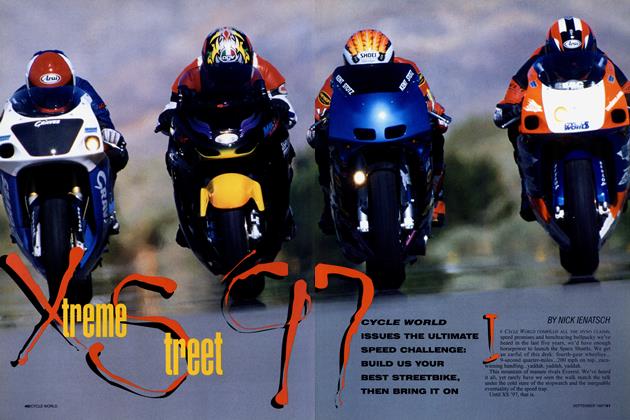

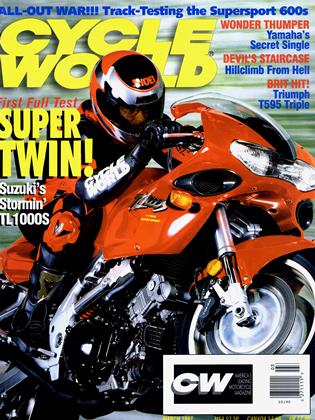

Exclusive test of Supersport 600s from Honda, Kawasaki, Suzuki and Yamaha on Daytona’s high banks

NICK IENATSCH

AN INFORMAL ATMOSPHERE masks the anxiety felt by those who attend Dunlop's annual pre-season tire test. Here, on Daytona's demanding, horsepower-sapping high banks, factory roadrace teams fire their first shots toward next season's championship. There are new bikes, new riders and new tires to try, but it's always the same old game of trying to optimize horsepower and handling.

Suzuki and Yamaha arrived in Daytona Beach with all-new models to pit against the veteran Hondas and Kawasakis. By the end of October, one of these four will wear the AMA 600 Supersport crown. Who has the pre season advantage?

HONDA CBR600F3

A fantastic streetbike that's also a bal anced road-racer If you were to pick the `97 supersport champion from assembled spec sheets, Honda's CBR600F3 might finish last. After all, in a year of sportbike revolu tion, Honda chose to minimally tweak its championship-winning middle weight, lightly massaging the engine, suspension and bodywork. But some where between retail price and wet weight should be a ranking for balance, because it is all-around competence that has kept Honda in the game. Few bikes, regardless of class, perform as well.

That said, Honda's on-track dominance is in for a serious challenge this year. In a word, the Honda is "ridable," its affable streetability transferring direct ly to the racetrack. The handlebars are mounted in the stock location above the triple-clamps, so the riding position feels relatively sedate compared to the hunkered-down Suzuki GSX-R600.

Even so, once you’ve settled into the CBR’s street-oriented ergonomics, you can really haul ass.

The F3’s 599cc engine loves to rev. It gets through the gears quickly, the tachometer needle racing toward redline (and beyond) with an eager-

ness that only the new GSX-R can match. With the exception of an onthrottle lag that can catch you off-guard mid-corner, carburetion is good. There’s a large gap between fifth and sixth gears that is especially noticeable at Daytona, but the bike’s broad spread of power handles the hole fairly well.

Honda may have packed a few more ponies into the engine (and sponsor Elf formulated a new blend of fuel reportedly worth 1.5 horsepower), but it’s the chassis that will be put to the test this year. The F3 is more nervous than the other factory 600s, needing an extra nano-second to compose itself in bumpy corners. But as Smokin’ Joe’s rider Steve Crevier says, “You leam to ride it loose.” Dunlop’s grippy new Sportmax D207 GP radiais certainly offer terrific traction, but they seem to overly stress the CBR’s chassis. Nonetheless, feedback at both ends is clear and direct (the Penske shock is fantastic), allowing the rider to push right to the edge of the traction envelope.

Basically, there are no categories in which the F3 fails to excel. But the strengths that carried it through past seasons have been equaled and even exceeded by the competition, most notably Kawasaki and Suzuki. Even though the CBR is wonderfully balanced, it’s time for Honda to get nasty and give us a CBR600RR.

KAWASAKI ZX-6R

One-time race winner in ’96, now with full-time Muzzy attention

Muzzy Kawasaki’s Tommy Hayden and Todd Harrington were introduced to their lime-green ZX-6Rs at Daytona. Both riders came away smiling, and so did I.

Daytona favors horsepower, and that’s what Kawasaki and Muzzy do best. Indeed, the K-brand topped informal radar-gun readings throughout testing. The ’97 ZX-6R is largely unchanged from last year, though the racebike reflects what the team learned during the ’96 season. “We set cam and ignition timing at home, and now we’re just fine tuning,” said team owner Rob Muzzy. “Now that we’re not racing in Europe, the 600 will be a priority.”

On the track, the ZX’s acceleration will stun anyone not accustomed to a modern supersport racer. Kawasaki introduced pressurized airboxes to the class, and Muzzy’s tuners have carburetion tuning down to an art. The engine spins hard to 13,000 rpm, but responds just as happily on a mellow cool-down lap. Shifting isn’t as precise as that of the Honda or Suzuki, but for all-out ooomph, the green meanie sets the pace.

As well as the Ninja works on the street, the racetrack demanded some significant chassis changes. Weight reduction was emphasized, and Muzzy’s modifications include an exhaust system made entirely of titanium. Up front, the 41mm fork appears stock, but close inspection reveals a brace mounted just below the lower triple-clamp. Besides the usual complement of preload and damping adjustments, the Ohlins shock wears a ride-height adjuster to fine-tune steering and traction.

Despite the changes, high-speed transitions, such as the left/right flick through the entrance to Daytona’s Chicane, tie up the front end as it struggles to keep up with steering inputs. The bike tracks nicely on the banking, but takes a few moments to settle down after a strong steering input or after a bump. Hence, the steering damper.

According to Muzzy, future efforts will be aimed at improving front-end feedback and braking feel. As for the latter, the fourpiston front binders, which were fitted with SBS pads, stop the bike really well, but they don’t offer the feedback necessary to trail-brake aggressively into Daytona’s two horseshoe comers. Harrington’s lap times, however, show that a good racer can adapt to the current set-up. If Muzzy can come up with a front-end combination that really “talks” to the rider, Kawasaki will take a giant-size step toward the top of the podium.

YAMAHA YZF600R

The last time Yamaha raced 600 Supersport, it took home the title Yamaha split with Vance & Hines after the ’96 racing season, pulling its program in-house. A single rider, Ohio native Tom Kipp, was hired to ride both the Superbike and supersport machines.

Despite the confusion, the all-new YZF600R looks terrific and shows considerable promise, even if numerous details are still undecided-at Daytona, Kipp and factory support rider Rich Oliver were still testing exhaust systems. “We’ve been through the engine and degreed the cams and done a valve job, but I expect a considerable performance gain when we finetune for the pipe,” said crew chief Tom Houseworth. “Basically, we’ve had two months to move the team, build our shop and prep the bikes.”

The team’s rushed preparation wasn’t apparent on the stopwatch or radar gun, though, as Kipp and Oliver circulated with impressive speed. The YZF’s long-stroke motor pulls hard, but doesn’t yet have the top-end punch of its competitors, flattening as the tach needle approaches 13,000 rpm.

Kipp and Oliver’s quick lap times came from the strength of the YZF’s chassis, the basis of which is a steelperimeter frame that exhibits superior bump-absorbing stability. Entering the Chicane, for example, you get ready for a wiggle, but the YZF’s chassis soaks up the ripples like a touring bike.

The price of this stability is heavier steering, which is especially noticeable when transitioning right then left exiting the Chicane. Kipp’s clip-on handlebars are mounted under the top triple-clamp, placing them about 3 inches lower than stock for an excellent racing posture. Reduced leverage, however, is the trade off. With the bike’s inherent stability, Yamaha could afford to get more aggressive with its chassis geometry at Daytona, adding rear ride height and lightening the steering until the bike became downright jittery.

The four-piston front brake calipers that proved so spectacular on the street feel numb when braking from Daytona’s daunting speeds. And I needed more than one brief test ride to familiarize myself with the conventional 41mm Kayaba fork. Each lap turned was quicker than the last, as I cautiously explored front-end feedback. Tweaking the fork’s internals and experimenting with brakepad compounds are on the YZF’s to-do list.

On the strength of the team, the Yamaha must be considered a threat for the championship. If Houseworth and company can add more top-end power, they’ll have a contender. But for now, the bike simply feels too street-oriented to run up front with the other 600 supersports.

SUZUKI GSX-R600

Mean little brother to the all-conquering GSX-R750 Prior to throwing a leg over Pascal Picotte’s GSX-R600 racebike, I already had two strong indicators of the bike’s ability. First, the GSX-R750 had dominated AMA 750cc Supersport racing in 1996. Second, Picotte has just circulated Daytona in 1 minute, 55.9 seconds, more than a second quicker than anyone else.

By themselves, the CBR600F3, ZX6R and YZF600R are eminently capable around a racetrack, but with the arrival of the GSX-R600, middleweight production racing may never be the same. Indeed, 750 supersport lap times are now within reach.

Because the bikes are so similar, the GSX-R600 received many of the same modifications performed on the championship-winning GSX-R750. Revised cam-timing specs, Yoshimura’s MultiPull Jet Needle System (MJN) and a titanium Duplex exhaust system rearranged the engine’s power curve, greatly improving driveablity. Chassiswise, Yoshimura ran the bike with revalved fork internals, a stock shock, a Showa steering damper and steelbraided brake lines, but stuck with the stock brake pads.

In racetrack parlance, the GSX-R lets you “ride the front end.” Simply stated, the Suzuki provides better front-end feedback than the competition, boosting confidence and encouraging experimentation. Most supersport racers require a leap of faith as the rider explores the machine’s limits-not so with the Suzuki, thanks to its 45mm fork and overbuilt aluminum chassis. Manic comer-entrance speeds are encouraged, just like on 250cc GP bikes.

Picotte likes a lot of rear ride height, so the result is a twitchy motorcycle, but one that feels purpose-built. Take your hand off the handlebar to look over your shoulder, and the bike wiggles. Grab the binders, and the rear end dances as the four-piston calipers shed speed like a machete through taffy. This heavy front-end bias would be a problem if the rear end didn’t hook-up out of comers. The Suzuki’s does. And since chassis flex isn’t a concern, the suspension can be dialed-in to better handle bumps and weight transfer.

In all, it’s a combination that should make the competition very nervous. This bike is ready to rock. If Dunlop’s Daytona tire test is any indication, 1997 could be the Year of the Gixxer in supersport racing.

CONCLUSION

Two days of testing revealed outstanding performance from each manufacturer. But Suzuki aimed its GSX-R600 directly at the racetrack, and the competition simply can’t match that commitment. Of course, we couldn’t measure one very important championship-winning ingredient: the riders. Factor in a Duhamel, a Kipp, a Harrington or any other bright talent, and the Suzuki’s mechanical advantage is only good for benchracing. Honda, Kawasaki, Suzuki and Yamaha will have 15 weekends in the coming year to duke it out.

All things being equal, though, don’t bet against the Suzuki. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Hopwood Chronicles

March 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsHow Many Bikes Do You Really Need?

March 1997 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCPractical Men

March 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1997 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha Shows Wonder Thumper!

March 1997 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupTraction Calling

March 1997 By Don Canet