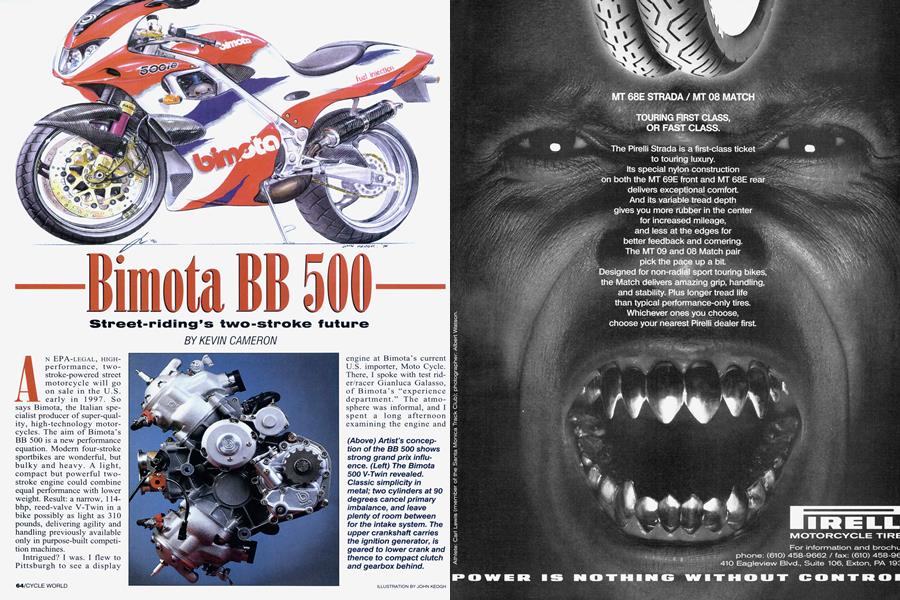

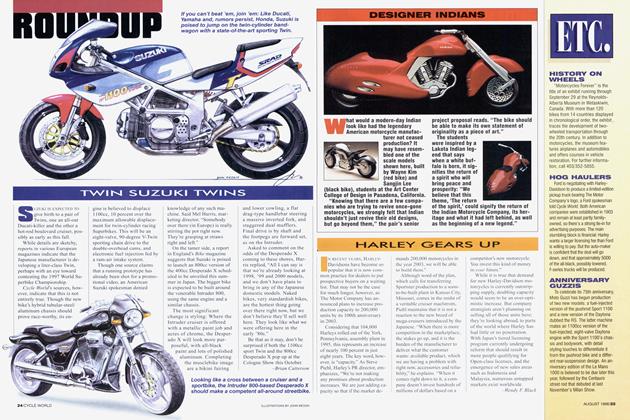

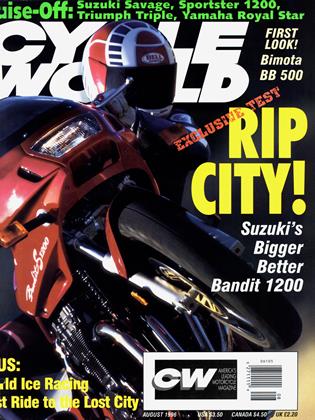

BIMOTA BB 500

Street-riding's two-stroke future

KEVIN CAMERON

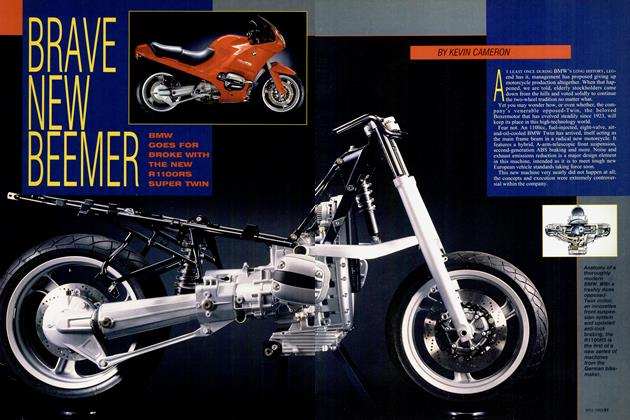

AN EPA-LEGAL, HIGH-performance, two-stroke-powered street motorcycle will go on sale in the U.S. early in 1997. So says Bimota, the Italian specialist producer of super-quality, high-technology motorcycles. The aim of Bimota’s BB 500 is a new performance equation. Modern four-stroke sportbikes are wonderful, but bulky and heavy. A light, compact but powerful two-stroke engine could combine equal performance with lower weight. Result: a narrow, 114-bhp, reed-valve V-Twin in a bike possibly as light as 310 pounds, delivering agility and handling previously available only in purpose-built competition machines.

Intrigued? I was. I flew to Pittsburgh to see a display

engine at Bimota’s current U.S. importer, Moto Cycle. There, I spoke with test rider/racer Gianluca Galasso, of Bimota’s “experience department.” The atmosphere was informal, and I spent a long afternoon examining the engine and hearing its development history from Galasso.

Bimota has a deserved reputation as a weathervane of motorcycle engineering. Timely new ideas, too radical for the major manufacturers, are put into production first by Bimota.

The non-telescopic front end of the Bimota Tesi is a prime example. For this small, 55-person company, ideas imply action. After Bimota “tests the water,” others may follow.

The last two-stroke to hit U.S. streets was the catalystequipped Yamaha RZ350 of the mid1980s, but the next

level of EPA standards swept it away. Bimota engineer Pierluigi Marconi will stop two-stroke emissions at their source-by preventing fuel loss from the exhaust ports by use of direct fuel injection (DI). Other newlydesigned low-emissions two-strokes use DI, too, but Bimota achieves it in a new way. With DI, the Bimota 500 has a regular idle-not the intermittent “ring-ding” idle of traditional twostrokes. “Boom-boom-boom, just like a fourstroke,” says Galasso.

Lubrication will be different, too. In the past, twostrokes have been lubed either by gas/oil mix or by injecting oil into engine intakes. On Bimota’s BB 500, oil goes only to bearings and cylinder sleeves,

in minimum quantity, from an engine-driven metering pump; the exhaust is smokeless. Sound impossible? Ford, in its two-stroke automotive research, was able to make its prototype engine burn less oil than its production fourstroke engines. Rolling-element bearings need very little oil.

The chassis of this precedent-setting Bimota will consist of almost nothing; a simple triangulated forward frame of oval tubing joins the rigid-mounted engine to the steeringhead, while a vestigial rear structure will carry the swingarm pivot and seat frame. Because of the engine’s twin-crank Vee configuration, vibration will be largely selfcanceling, allowing the crankcase to be used as a stressed chassis member in the modem style.

Now recall the emissions problem that killed two-stroke road bikes in the 1980s, and consider the technology that may revive them in the late 1990s. In traditional twostrokes, fuel is added as air is drawn into the crankcase through a carburetor. This fuel-air mix is then compressed in the crankcase as the piston descends. The moving piston first uncovers the exhaust port, and then the transfer ports. The compressed fuel-air mix rushes up through the transfers with the exhaust port open. Inevitably, in the process of chasing out exhaust remnants and refilling the cylinder, some fresh charge is lost out the open exhaust port.

At idle, the situation is worse. With little fresh charge entering a cylinder filled with inert exhaust, the engine may not fire at all because the fresh charge is too diluted. It therefore takes several revolutions before enough fresh charge accumulates in the cylinder to allow ignition, with much fuel being pushed out the exhaust in the process. This irregular part-throttle firing can waste 75 percent of the fuel and causes the two-stroke’s “ringding” idle. These fuel lossesunburned hydrocarbon emissions-are what forced two-strokes off American highways.

Onward maker, its three-cylinder to Motobecane, the revival! tested 350. In Instead the an early early of taking 1970s, form of in a fuel-air French DI on mix, the crankcase took in only pure air, which was then used to scavenge and refill the cylinder. Only when the exhaust port was nearly closed was fuel

injected directly into the cylinder. It was tricky to get the injected fuel to evaporate in the short time available (Vó to V4 of a crank revolution, as compared with nearly a whole revolution in a four-stroke), but when the thing worked, it worked magnificently; power remained high, but fuel consumption was cut in half. Don’t confuse DI with fuel-injection systems that simply replace the carburetor with a throttle body and fuel injector. Such systems-like the PGM system Honda has tested on its GP bikes, or like snowmobile systems-do not significantly reduce emissions.

Motobecane’s work was largely ignored because the rush to four-stroke power was on. Honda was already producing the CB750 and Kawasaki’s Z-l was just around the corner. It was easier to use existing fourstroke technology than to struggle with Motobecane’s tricky new idea.

The next step came in the mid-1980s, when the Australian Orbital Engine Co. demonstrated an air-blast fuel injector that could shred fuel small enough to evaporate in the necessary short time. That, in turn, stimulated a fresh look at two-stroke power all over the globe. From 1989-91, more than 20 DI two-stroke development projects were underway in the labs of Ford,

General Motors, Mercury Marine, Toyota and others. Two-stroke DI was hot.

Why the interest? Auto-makers, caught in the ever-tightening noose of emissions and fuel economy standards, were desperate for new answers. And the truth is that once DI is applied, two-strokes become potentially more efficient and less polluting than four-stroke engines of

equal power. Their low mechanical and pumping losses, their lightness and lack of bulk make them a natural for the highly streamlined, low-hoodline modem automobile.

Since 1992, uncertainty about the direction of future emissions regulation has put the automotive two-stroke on the back burner, but Mercury has its new DI outboard on the market and one or more snowmobile makers aren’t far behind. For motorcycles, the two-stroke is more attractive than ever. Bimota engineers surely asked themselves why sportbikes are as bulky and heavy as they now are. Is a powerful sports car 20 feet long and as heavy as a Cadillac? A return to two-stroke power-now with greatly reduced emissions-could reverse this spiral toward bulk and weight.

In our emissions-regulated era, there can be no going back to simple, everyman’s motorcycles like the Yamaha RDs of 20 years ago. Bimota cannot make a machine for the masses. But they can take the first step. They can demonstrate the new technology in a lighter, smaller, more agile sportbike with top performance. The big makers all have twostroke prototypes like the BB 500 running in their R&D programs, but they are content to watch Bimota for now.

Originally, this 500 engine was designed for GP racing as a conventional carbureted twostroke. It was then redesigned by Marconi with his unique direct injection. Instead of trying to make the injectors break up the fuel into tiny, fast-evaporating droplets, Marconi used piston heat to evaporate it. Using lowtech, low-pressure automotive injectors, he shot the fuel streams onto the hot piston. Its high temperature flashed them into vapor that was instantly swept up by the transfer streams. This is analogous to the many four-stroke injection systems that direct fuel onto the backs of

the hot intake valves. Two-stroke pistons run hot because there is combustion every revolution, not every other revolution as in a four-stroke. Marconi’s injection scheme makes a virtue of piston temperature. According to Galasso, piston deposits have not been a problem.

Aside from its DI fuel system, the BB 500 engine is conventional. Two small-diameter cranks lie one above the other in Aprilia GP bike style, with one Nikasil-lined cylinder sloping up and forward, the other down and forward. A compact cassette gearbox sits behind. Between the cylinders lies the big 5 x 5-inch intake box with its four 40mm butterfly throttle bores serving a pair of reed blocks. Flow from the reeds enters each crankcase in a smooth, well-thoughtout way, without the compromises of size and direction that afflict the tight packaging on single-crank designs like Yamaha’s current TZ250 race engine.

Italy is a hotbed of specialized know-how. Galasso spoke with audible reverence of the collective experience of Ferrari and its circle of suppliers. When Marconi sought injectors capable of operating at the BB 500’s 9000-rpm redline, it was a tall order, equivalent to a four-stroke injector that could reach 18,000 rpm. But WeberMarelli had just the thing-a tiny injector designed especially for Ferrari F-l use three years ago. Each of the BB 500’s cylinders carries two of these, aimed down toward the piston from holes in the cylinder walls above the transfer ports. Fuel is supplied to them at 80 psi by an electric pump, and all injectors fire simultaneously.

In a two-stroke, big pis tons usually mean big heat problems-like those Aprilia has expe nenced with its 400cc GP Twin. These take

the form of piston-dome collapse (as the overheat ing piston turns to Jello), or outright seizure. Marconi has dealt with this by con necting the piston's vulner able central region to the wristpin via webs, shorten ing the heat path and giving extra support.

This engine's racing ori gin is obvious in its short stroke (72.0 x 61.25mm), its cas sette gearbox and its gyro-effect-canceling contra-rotating cranks. As part of development, the BB 500 was run in the Italian National Championship races in 1993.

“We had many troubles,” Galasso recalls, but against unlimited four-strokes, the developing Bimota 500 held its own, with a best finish of third. More than 130 horsepower was achieved, at 1 1,500 rpm. But all of this is irrelevant compared with the important central feature of this design: Marconi’s heatevaporated, low-tech direct-injection scheme.

The engine has full computer control of ignition timing and fuel injection, and, unlike many systems we have seen, fueling is not “mapped.” A mapped system cannot measure engine airflow or combustion conditions, but blindly injects the amount of fuel that its “map” (stored instructions) tells it is correct for that particular throttle opening and rpm. The BB 500’s system measures oxygen content in each exhaust pipe, and continuously corrects mixture strength accordingly. With this sophisticated control, the BB’s fuel consumption is very low-lower than an equally powerful fourstroke’s-and it is expected to meet U.S. emissions standards handily.

Rely upon Bimota to make the new machine visually pleasing as well as technically fascinating and revolutionary. Italian design underscores the insistence of the late John Britten that beauty and excellence in engineering are part of a single aesthetic-not separate and unrelated.

It’s appropriate, too, that Bob Smith, the own-

er of Moto Cycle, came from an arts background before taking over the importation of Bimotas. Clearly, there is more than one path to the appreciation of machines like the soonto-be Bimota BB 500. One of the pleasures of importing

Bimotas, Smith says, is meeting the variety of unusual people who are attracted to these highly aesthetic motorcycles.

he factory's current sched ule calls for the complete BB 500 to ap pear at the

Cologne Show in the fall, enter “alpha test” worldwide in pilot production form thereafter and reach the American market in 1997. Until then, we have the pleasure of knowing that the major manufacturers are watching the new Bimota as closely as we are.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue