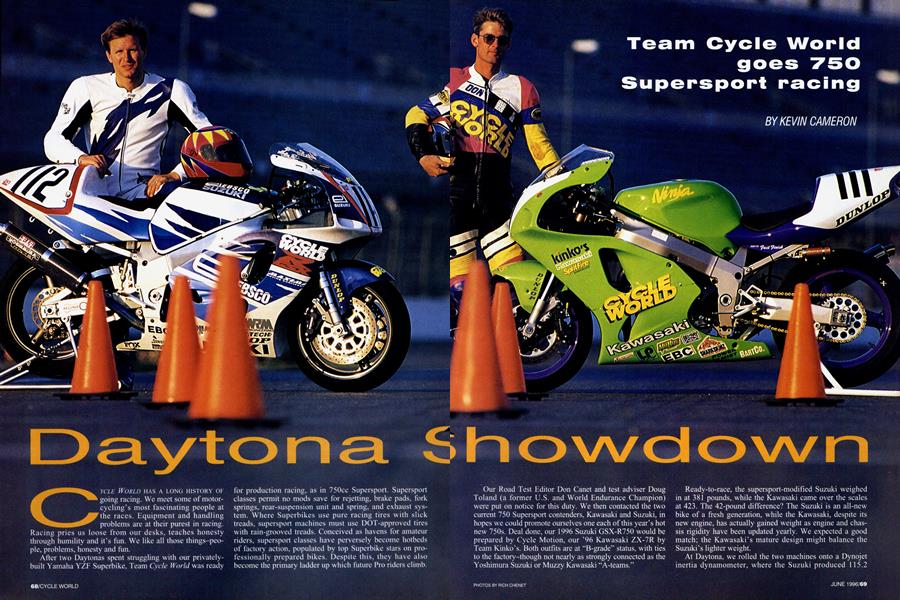

Daytona Showdown

CYCLE WORLD HAS A LONG HISTORY OF going racing. We meet some of motorcycling’s most fascinating people at the races. Equipment and handling problems are at their purest in racing. Racing pries us loose from our desks, teaches honesty through humility and it’s fun. We like all those things-people, problems, honesty and fun.

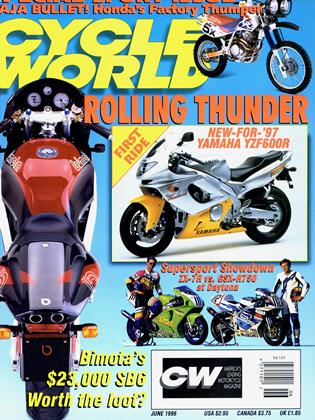

After two Daytonas spent struggling with our privatelybuilt Yamaha YZF Superbike, Team Cycle World was ready for production racing, as in 750cc Supersport. Supersport classes permit no mods save for rejetting, brake pads, fork springs, rear-suspension unit and spring, and exhaust system. Where Superbikes use pure racing tires with slick treads, supersport machines must use DOT-approved tires with rain-grooved treads. Conceived as havens for amateur riders, supersport classes have perversely become hotbeds of factory action, populated by top Superbike stars on professionally prepared bikes. Despite this, they have also become the primary ladder up which future Pro riders climb.

Team Cycle World goes 750 Supersport racing

KEVIN CAMERON

Our Road Test Editor Don Canet and test adviser Doug Toland (a former U.S. and World Endurance Champion) were put on notice for this duty. We then contacted the two current 750 Supersport contenders, Kawasaki and Suzuki, in hopes we could promote ourselves one each of this year’s hot new 750s. Deal done, our 1996 Suzuki GSX-R750 would be prepared by Cycle Motion, our '96 Kawasaki ZX-7R by Team Kinko’s. Both outfits are at “B-grade" status, with ties to the factory-though not nearly as strongly connected as the Yoshimura Suzuki or Muzzy Kawasaki “A-teams.”

Ready-to-race, the supersport-modified Suzuki weighed in at 381 pounds, while the Kawasaki came over the scales at 423. The 42-pound difference? The Suzuki is an all-new bike of a fresh generation, while the Kawasaki, despite its new engine, has actually gained weight as engine and chassis rigidity have been updated yearly. We expected a good match; the Kawasaki’s mature design might balance the Suzuki’s lighter weight.

At Daytona, we rolled the two machines onto a Dynojet inertia dynamometer, where the Suzuki produced 115.2

rear-wheel horsepower, the Kawasaki 114.4. Not only did the two bikes produce similar power, but their power curves even had similar shapes.

Our riders were good enough to qualify 12th (Toland at 1:58.7) and 14th (Canet at 1:59.2), despite the expected difficulty of matching rider, bike and team in very little time. Daytona, as always, had surprises in store. The race began with more of the high wind that had plagued qualifying, and American Suzuki/Yoshimura riders Aaron Yates and Pascal Picotte cleared off from the field for their own private duel. Canet, on the Kinko’s Kawasaki, found himself initially paired with young lion Jason Pridmore on another Kinko’s ZX-7R, but lack of a last-minute sprocket change left him geared wrong in too many places. Don explained, in his flat-affect style, that he had also displayed “journalists’ syndrome.”

“I didn’t want to be remembered as the magazine guy who knocked Jason Pridmore down. So when we’d get into a corner together, I thought I ought to give way.”

Despite this, it was heartening to race with Pridmore, even for a time. While Yates and Picotte motored away for a crushing 1-2 finish and Muzzy rider Doug Chandler worked hard to get his Kawasaki into third place, Pridmore moved up to seventh overall, second Kawasaki (of the first 30 finishers, 21 were GSX-R-mounted). Don would finish 15th at the end, fourth Kawasaki.

Toland had searched for a suspension combination in practice, and had crashed the previous week, buckling a frame, which required a laborintensive replacement. On a setup far from ideal, he pressed the Cycle Motion Suzuki to 11th place at the end of the 15-lap, 51-mile race.

Production bikes are fabulously quick now, and in supersport trim are even more impressive.

Picotte, who finished a close second to Yates, had qualified at a sensational 1:54.6, which would have put him 19th on the Superbike grid-this on a nearproduction bike, on DOT tires.

How close to stock are supersport machines? Only the builders know. Some say that loose clearances and thin oils make power, while others hint about “Specially Dimensioned Parts.” SDPs work like this: If you have your own factory and want, let’s say, extra compression, you could run off a batch of con-rods that were a couple of thou longer than average, some pistons a bit taller, cylinders a bit shorter. Okay, now the tech inspectors set a > spec for deck height to stop this practice, so you move to the cylinder-head production line. You adjust the tooling to remove less material from the cambox side of the head, more from the head gasket surface. Now you have a head with standard thickness, but reduced chamber volume.

Yet another approach was popular three or tour years ago, when it was legal to replace all the valve seats with taller ones ($2500 at your friendly machine shop), thus boosting compression by pushing the valves deeper into the combustion chambers. Now limits have been set. -

Or imagine a "special inspection station" on the cylinder head production line. Heads with outstanding valve-seat insert concentricity are diverted to a flowbench, and the best-flowing examples are set aside. Whoever can look over the most heads, wins. Only the factory sees them all.

And what if a different swingarm-pivot height or steering geometry turns out in tests to be temptingly better than stock? Do you stick with morali ty, hoping others will do the same, and wait for the improvement to come on the next model? Or do you make up parts that look right but aren't stock (DCEs, for "Deformed Chassis Elements")? If you have scruples, you can always remember the old counterfeiter, who said, "If it passes, it's money." Under this

definition, anything that slides past tech inspection is certifi ably stock. If you believe the rumors, there's plenty of this kind of work going on.

For everything the tech inspector does, there is a fresh answer and, as veteran builder Vic Fasola once told me dur ing teardown, "The guys who are building these bikes every week are always going to be ahead of somebody who just measures them a few times a year."

Not true, you say? Factory riders are good enough to win on stock bikes? Maybe, but what if two or more factories are involved? Suddenly, even the best possible riders need every bit of help the race (and production?) department can give them-no matter how they get it. It's hard to walk through the pits without tripping over all the rumors. Is this just sour grapes from backmarkers? Here is what I believe: Any power-boosting or chas sis-improving technique you can think of is probably being used by somebody. The stakes in Supersport are big-the factories need to sell bikes, and up-and-coming riders are desperate to get noticed.

I talked to the men who prepared the Team Cycle World bikes. Cycle Motion’s Carry Andrew has many years’ experience and he emphasizes practical engineering. He checks front and rear suspensions with springs removed to be sure everything moves freely. He checks wheels and bearings likewise. Removing the cylinder head, he visually inspects it for seat-insert concentricity. Then he does a multi-angle competition valve job, being careful not to sink the allimportant 45-degree seat-every time the valves are reseated, compression ratio falls as the valves recede into the head. Reinstalling the head with the original gasket, he degrees the cams “to the numbers I like.” These new GSX-R engines, he says, have generous valve-to-piston clearances of .080-inch intake, .110-inch exhaust, which gives plenty of latitude for cam rephasing. Piston-to-head clearance (socalled squish) he likes to have at ,68mm (.027-inch).

If there is time for a full engine build, Andrew likes .0018-inch clearance for crank main bearings, .002-inch for the rods. These are not loose clearances, but are typical for Superbike engines.

Carburetion is very important, but several approaches are possible. “Pretty good results,” Andrew says, can be had with stock needles, simply raised with tiny washers. The Dynojet kit requires drilling a hole in the slide to slow its lift, thereby enriching snap-throttle response. The Factory Tuning kits, he says, use clip-type needles similar to stock. The aim, of course, is to find the combination that gives sharp response, maximum acceleration and top speed.

Our GSX-R’s exhaust pipe was a titanium Yoshimura unit of 4-2-1 design, without interconnects or resonators. A 4-2-1 pipe emphasizes powerband width-important in Supersport where a Superbike’s close-ratio gearbox cannot be used.

In any stock class, break-in is important. Andrew likes to run supersport bikes on the street for hundreds of miles if there is time, but notes he has had decent results with quickie break-ins when necessary. Because today’s synthetic oils have enough film strength to prevent break-in from occurring, Andrew breaks-in the piston rings for 150 miles with a petroleum oil, then completes the 500-mile break-in with synthetic oil. Andrew agrees with many other builders that engines won’t break-in properly under light throttle. The idea

is to put real pressure behind the rings (heavy throttle), but intermittently. This applies pressure to force parts to bed-in against each other, then allows the friction surfaces to cool as the oil system flushes the wear particles out to the filter.

Brake discs, too, must be broken-in. Andrew applies street braking load to new discs gradually, noting that they may warp if suddenly subjected to racing heat load.

Team CWs bike was equipped with a Fox shock and steering damper. The clutch and its springs were stock, and survived Speed Week without attention.

Over at the Kinko’s camp, I was received by Manager Robert Nutt and Crew Chief Scottie Beach in their comfortable, color-matched transporter. Beach stated the team emphasizes two main areas: carburetion and suspension.

“Unfortunately,” he observed with a twinkle in his eyes, “the team we work for has ruled out the use of ‘certain techniques,’ so we work hard with what is left.” Beach is a serious man, but humor emerges subtly, as it did during his subsequent discussion of such things as Specially Dimensioned Parts and Deformed Chassis Elements perhaps used by certain “others.”

Beach said that build quality on new production engines is now so good that little correction is necessary for things like cylinder roundness and crank/rod bearing clearances. Cylinder heads no longer display misaligned valve-seat inserts. Recent engines are very good.

Handling and carburetion are this team’s important work areas because bikes spend nearly all their time either accelerating or tuming-and very little time singing top-end’s high, sweet song. Team Kinko’s is cultivating a relationship with Penske Suspension because it believes that component quality and rapidity of adjustment save them time in matching machine to rider. Everyone faces a learning curve, and anything that saves time slides that curve to the left, giving the rider an advantage. When it comes to dialing-in a shock, too many riders and tuners, Beach notes, think they can “get it on the knobs,” meaning they can find correct suspension adjustment on the clicker knobs. These are only trimmers, and change just the low-speed damping. But to remove the shock, strip it and restack its valve shims to adjust middleand highspeed damping takes time. The Penske shock, by building in more external-adjustment capability, offers to bypass this.

The purpose of carburetion work is to deliver power when the rider needs it, in a form he can use. A super-potent engine that requires throttle fiddling at certain rpm is the kiss of death to lap times, as the rider wastes precious fractions of a second getting on the gas. A better payoff comes from a setup that delivers smooth, predictable, on-time power that lets the rider begin his off-corner drives sooner. Speed added at the beginning of the straight is far more valuable than speed added at the end-even at Daytona.

Like the Cycle World Suzuki, our Kawasaki carried a 4-2-1 pipe for broad power, but made by Muzzy. This, too, is a titanium pipe (ti is much lighter than steel) with the 1 & 2, and 3 & 4 pipes joined about 12 inches from the head.

A Stack tachometer was used, with a shift-light, set to turn on 200 rpm before the rev limiter hits at 12,800. Canet loved this feature. He could keep his eyes on the track and see the light’s reflection in the screen, “just like a fighter jet’s heads-up display,” he said.

This concludes Cycle World's snapshot glimpse into Supersport roadracing. Our bit of digging into the subject turned up, as usual, more questions than answers. Supersport is many things: gateway for young riders, all-out factory battlefield, spawning-ground for new highly organized secondlevel teams like Kinko’s. It’s an interesting arena that has yielded the best stock sportbikes ever. What next? □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue