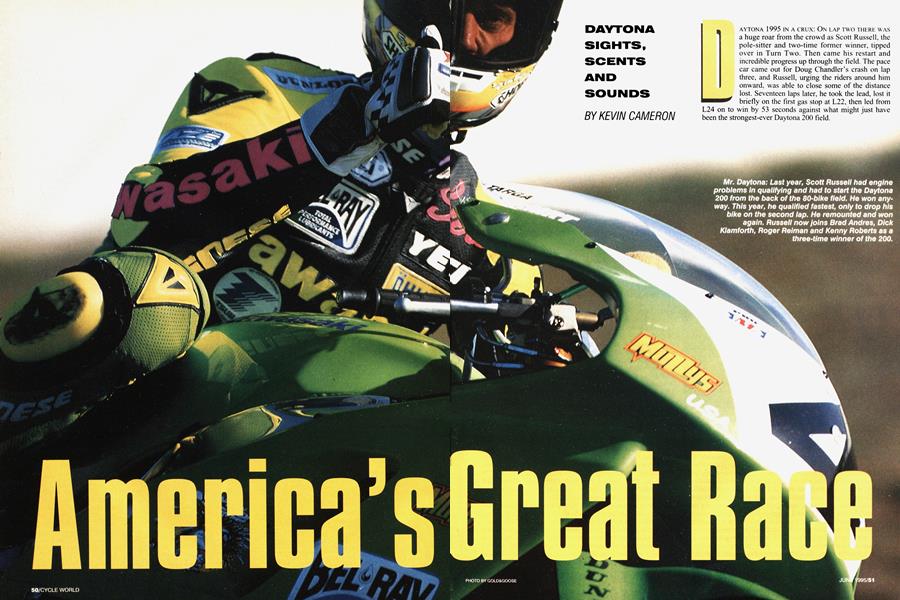

America's Great Race

DAYTONA SIGHTS, SCENTS AND SOUNDS

KEVIN CAMERON

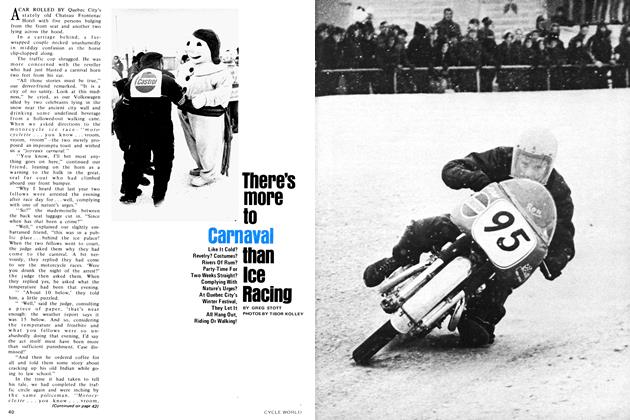

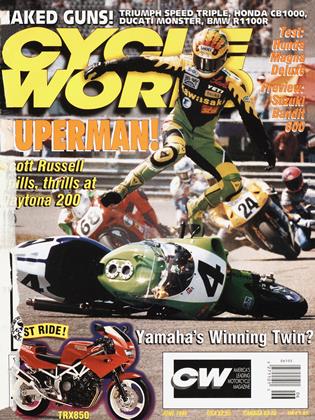

DAYTONA 1995 IN A CRUX: ON LAP TWO THERE WAS a huge roar from the crowd as Scott Russell, the pole-sitter and two-time former winner, tipped over in Turn Two. Then came his restart and incredible progress up through the field. The pace car came out for Doug Chandler’s crash on lap three, and Russell, urging the riders around him onward, was able to close some of the distance lost. Seventeen laps later, he took the lead, lost it briefly on the first gas stop at L22, then led from L24 on to win by 53 seconds against what might just have been the strongest-ever Daytona 200 field.

How can Russell come from behind, as he has now done twice, and catch riders capable of lapping even faster than himself? (Britain’s Carl Fogarty, on the Ducati Corse 916/955, set the fastest race lap.) Even magic requires a physical basis. What is it? Russell has learned how to make tires last on this difficult track. Sustained high speed and the extra loading of the 31-degree banking generate great heat. That forces the tire makers to provide tires of finely judged hard-

ness and durability. For this reason, Russell says you can’t go as hard here as you would otherwise; the tires won’t put up with an unrestrained charge. I believe Russell does what Kenny Roberts described long ago. When he feels that a certain band on the tire is starting to fry and go away, he shifts his hardest demands to a slightly different lean angle, and “rests” the overworked part for a few laps. As the qualifying results show, there were lots of riders at Daytona who were merely fast-but there was only one fast long-distance runner: Scott Russell.

Like other great Daytona winners, Russell also knows that there are certain crucial performances that must be right: getting into Tum One, and into the Chicane. Russell surely pushes hardest where the biggest potential gains lie, and can then afford to slightly rest his tires and himself elsewhere.

■ ■ ■

Russell was smiling and happy after the race, but his mood soon darkened. Second-placeman Fogarty, defending World Superbike Champion and an intensely competitive person, began to mix rudeness into his own disappointment. When it was Russell’s turn to speak, he didn’t look over to Fogarty for the one microphone, he just swung his hand that way and kept looking out at the roomful of journalists. Asked about the second-lap crash that made his race so dramatic, he said, “I just laid it in there, touched the throttle....”

When an English journalist questioned the use of the pace car, which had canceled much of Russell’s handicap on lap four, Russell sprang from his seat and said, “That’s it. I’m going home.”

■ ■ ■

Ducati Corse, European counterpart to the Ferracci team, did a Fine job at their First Daytona, but Fogarty got a wrong signal and pitted when the crew wasn’t ready, costing 10 seconds. Their second stop took extra time, as well. But after that, they had a full fuel can and a hot rear tire constantly at the ready in case of emergency.

With body panels off, the factory Ducatis displayed their magnesium side covers in chalky green chemical Finish. Everywhere on this machine are shiny black carbon panels, ducts and brackets. Ducati pipes no longer use a crossover tube, joining the two headers. Instead, the pipes “kiss” for about 5 inches, and an oval opening joins them. On the Harley VR 1000s, a similar idea was implemented with four 3/4-inch cross-pipes. The lower fork crown on the 916s is so vertically deep, with a great arching web connecting the right and left sides, that it resembles an aluminum pair of shorts. Each side has three pinch bolts. Further evidence of full racing seriousness is hinged clip-ons, which can be replaced pronto without removal of the top crown.

The new Ducatis are incongruous, though; although their exterior looks are svelte and compact, they wrap around a big, bulky engine. Every year that a given design is raced, mechanics and engineers accumulate fresh ideas about how to speed service, how to fit components together better. Mature designs have an attractive simplicity that comes from this process.

■ ■ ■

Kawasaki will have a new machine next year, after five years with the present design. “I’ve ridden it,” Russell said. “Well, half of it.” He was talking to well-wishers outside his motorhome on Saturday afternoon, genial and relaxed. “The chassis is everything,” he continued. “Engines-that’s the easy part.”

I asked both Muzzy and his chief of staff Steve Johnson whether they feared a new design would cripple the team as new designs have other teams.

“Well, I hope not,” said Muzzy, noting that the new machine has been under long development. “We’re smarter than that,” affirmed Johnson.

■ ■ ■

For subtle color, nothing rivals the effects of welding heat on titanium exhaust pipes. Pale straw grades into yellows and darkening blues and violets close to weld lines. This results from formation of interference coatings of heat-generated surface oxides, analogous to how an oil film on water generates colors. The metal itself has a unique dry metallic sheen. At one point, Miguel DuHamel’s 600 F3 Honda had a pipe change, from a 4into-2-into-l to a 4-into-l plus divided rectangular collector. It was surrounded with all the pieces of both systems lying on the shop floor-beautiful Tinkertoys.

The factory RC45 Superbikes likewise had a choice of systems-a top-end system with two mufflers, and a midrange system with one.

The Harley VRs are always started with a roller, and once started, they warm up with a riveter-like, quick bap-bap-bap drumbeat. On the track, their sound is quite distinct from that of the Ducatis. Although both are V-Twins, the Ducatis are so muffled (joined exhaust, twin mufflers) that on the straightaway they sound like hard blowing across the mouth of a bleach bottle-deep and breathy. The VR has a sharperedged bellowing sound, more like a WWII fighter plane making a low pass.

Gears, cams and linkages are noisy, too. At first, both the Honda RC45 and Ducati 955 (now in the sensual 916 package) sound similar while warming up. But the RC’s noise comes mainly from its geared camdrives, and has a growly, muted-rock-crusher sound that RC30 owners know well.

The Ducati’s sound is higher-pitched, coming from all the action in its springless desmo valvetrain; its rubber toothbelt camdrives are silent.

The sharpest, highest on-track sound comes from the Suzuki GSX-Rs, which despite three years of development, have yet to reach parity with top Superbikes. Lead rider Thomas Stevens did a fine, canny job of staying upright and fending off competition to finish third, nevertheless. The sound from both the Yamahas and Kawasakis was so muted as to nearly blow away in the extremely windy conditions during qualification. That whistling-in-your-teeth sound heard along pit wall was Yamaha primary gears as the bikes pulled out to qualify.

Speaking of qualification, in that gusting wind, Russell went out and hammered the lap record down into the l:49s-a first. He looked superb, getting his machine way, way over, showing the smoothness that makes a performance look easy and inevitable.

The AMA has banned use of carbon-carbon brakes-as Honda manager Gary Mathers notes, “Just as our supplier was about to cut their price 40 percent.” The reason for the ban? To cut the expense of racing. Ah, but no one can be right all the time. No one was moaning about poor brakes, but there will be opportunity for that at tracks like Loudon. Honda has drawn a laugh with its latest Showa fork. So close is its resemblance to Swedish Öhlins suspension (some say parts may even interchange) that wags are calling the new equipment “Shohlins.”

Not so long ago, ram airboxes were big news. Finally, all major teams have the essential elements: l) a forward-facing intake in a high-pressure region; 2) a generous-sized smooth duct to the airbox (no white flex hose from the poolsupply service); 3) a diffuser, in which the duct enlarges to decelerate the air, efficiently converting its velocity into pressure (Suzuki is last with this feature, but they have it now); and 4) an airbox of adequate size so that each gasp of the engine does not significantly pull box pressure down (Harley and Yamaha are marginal here).

The fuel stops look frantic but the experienced teams don’t rush and everything slides into place. The bike stops at the board, a crewman steps forward and positions the dumpcan, with its two couplers, against the matching fitting on the tank top. The rider leans back, out of the way. It takes a slight shove to make the dry-break couplers engage against their return springs, and then you see a mix of fuel and air come frothing up the vent line. When it settles, the tank is full and the dumpcan is pulled. If the O-rings are fresh and properly lubed, there is hardly any leakage. Meanwhile, the rear end has gone up on a stand, either a simple lever stand or one of the fancier prong stands-maybe with an airjack. The air wrench chatters, the axle is pulled and the wheel comes out. Prior to the stop, one of the tires in heating blankets is inspected for tire number. Just before the stop, the blanket comes off and the hot tire and wheel goes over the wall for the change. Gloves are worn. Factory bikes now sport little “aids” like CNCmilled stand hooks, white nylon bellmouths to allow slapdash insertion of stand prongs, and swingarm-mounted supports to catch and hold the new wheel where the axle will slide in perfectly. Perhaps most importantly, as with an AK47, nothing is made as a tight fit. That way it goes together fast even when dirty, even in a brainless hurry. The quickest stop for a tire and gas took under 10 seconds.

Powermist race fuel (Kawasaki, Yamaha) smelled like a gas station, the traditional racing gasolines were sweet with alkylate, rich in the four valued iso-octane molecular structures. The popular ELF fuel attacked the nose with MTB ether. Uniquely, Ducati Corse’s Agip (pronounced Ah-Zheep) fuel reminded everyone of chem lab or the New Jersey Turnpike. It seemed that the whole garage area smelled subtly of battery acid, as there were batteries on (over)charge everywhere. “Men with batteries,” is how veteran two-stroke racer Miles Baldwin once tersely described Superbike racing.

Vance & Hines’ team has received the presence of Yamaha’s MX guru, Keith McCarty, as a kind of senior systems analyst. Chassis performance has likewise benefited from an adjustable swingarm pivot height on the YZF. Normally, chain tension from engine power generates a lift force at the back that counters the natural weight transfer to the rear. The danger in rearward weight shift is a loss of grip at the front; a bike that squats under acceleration is likely to “push,” or run wide. The better the front grip, the more power the rider can use off the corners. Changing the pivot height allows lift force to be adjusted to counter squat, so push can be controlled. Progress.

The current international character of the Daytona 200 tends to obscure the fact that it is Suzuki’s third-finishing Thomas Stevens who comes away with top national points; both Russell and Fogarty are World Superbikebound. Teammates Fred Merkel and Donald Jacks rode smart, conservative races to finish eighth and ninth, giving Suzuki three men in the top 10. GSXRs haven’t had such a grand result in years. Next year it is strongly rumored that Suzuki will have a fresh design, but don’t

feel too sorry for the company’s long-running dry spell in Superbike racing. GSX-Rs sell, and Suzuki has put lots of us on fine sporting machines at an affordable price-something you can’t say for YZFs and RC45s.

Harley-Davidson knew going in that, although they’d made headway in their struggle for more power, so had the others. Their top qualifier was Doug Chandler down in 21st grid spot. When Don Tilley’s rider Scott Zampach showed 167 mph on radar during practice, much was made of it. Tilley, a great character who looks and talks as if he’s just walked off the set of “Lonesome Dove,” reminded them that, “A decade ago we went 170 with Lucifer’s Hammer” (a special Battle of The Twins racer powered by a twovalve, air-cooled Harley engine of the same displacement as the VR). That put it all back in perspective.

As last year, the VRs handled exceptionally well, but power is the issue. For reasons unknown, the VR’s power is a lot like that of a dirt-track XR; the torque is at the bottom, and the engine winds its way to peak power thousands of revs above. This is ideal on the mile, but in roadracing,

you’d like peak torque up higher where it can boost peak power (power equals torque times rpm, essentially). Lots of new combinations have been tried—partially filled ports, a multitude of exhaust systems, various piston treatments, cam timing, fuel-injector location.

Rumor from Britain has it that Lotus is in process of developing a “VR II” cylinder head under contract. Rumor in the U.S. holds that VR heads have been sent to other consulting engineers as well-just as Honda did with its air-cooled 1025 cylinder heads back in 1980. Any way it happens, I will be delighted to see the VR1000 become fully competitive. Harley stockholders don’t have to personally do the porting to satisfy me.

Daytona is not about being ready. No one is ever ready for Daytona. Daytona is about coping. This year, Russell, Muzzy and Kawasaki coped best.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontDoin' the Wave

June 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

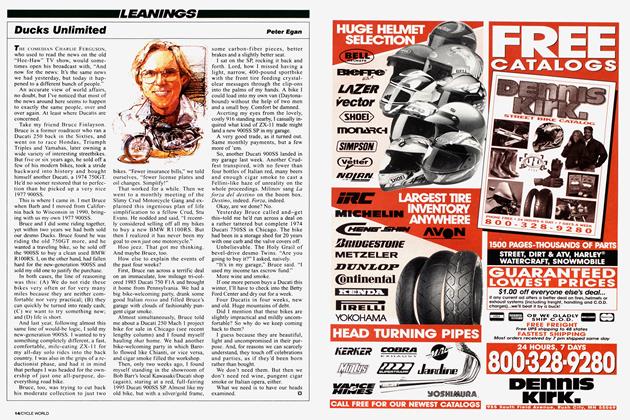

LeaningsDucks Unlimited

June 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCAlloy Connection

June 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupBandits Coming Soon To Your Neighborhood

June 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Surprise Single

June 1995 By Robert Hough