CONFESSIONS OF A REFORMED BIKE THIEF

A REFLECTION ON SIN AND REDEMPTION

Wendy F. Black

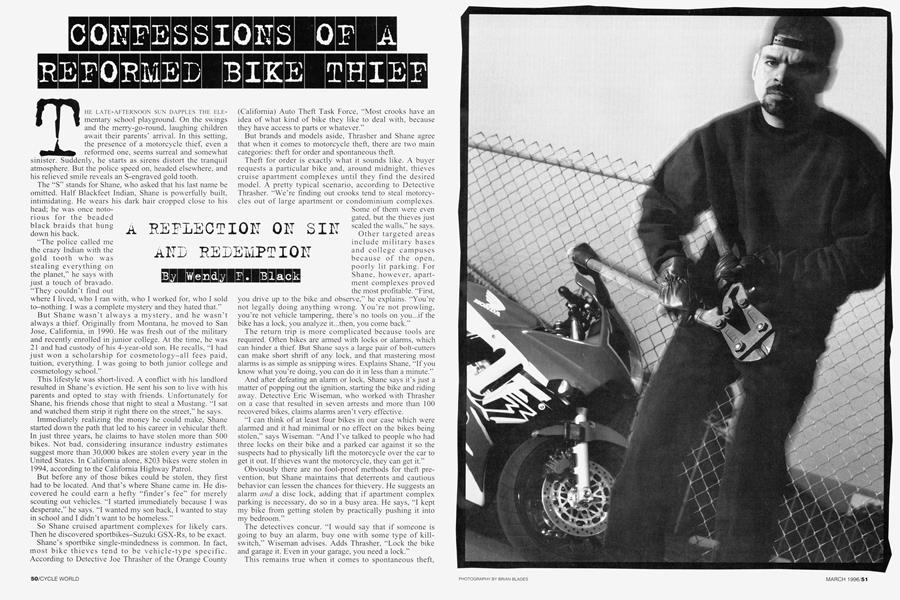

THE LATE-AFTERNOON SUN DAPPLES THE ELEmentary school playground. On the swings and the merry-go-round, laughing children await their parents' arrival. In this setting, the presence of a motorcycle thief, even a reformed one, seems surreal and somewhat sinister. Suddenly, he starts as sirens distort the tranquil atmosphere. But the police speed on, headed elsewhere, and his relieved smile reveals an S-engraved gold tooth.

The “S” stands for Shane, who asked that his last name be omitted. Half Blackfeet Indian, Shane is powerfully built, intimidating. He wears his dark hair cropped close to his head; he was once notorious for the beaded black braids that hung down his back. “The police called me the crazy Indian with the gold tooth who was stealing everything on the planet,” he says with just a touch of bravado. “They couldn’t find out where I lived, who I ran with, who I worked for, who I sold to-nothing. I was a complete mystery and they hated that.” But Shane wasn’t always a mystery, and he wasn’t always a thief. Originally from Montana, he moved to San Jose, California, in 1990. He was fresh out of the military and recently enrolled in junior college. At the time, he was 21 and had custody of his 4-year-old son. He recalls, “I had just won a scholarship for cosmetology-all fees paid, tuition, everything. I was going to both junior college and cosmetology school.”

This lifestyle was short-lived. A conflict with his landlord resulted in Shane’s eviction. He sent his son to live with his parents and opted to stay with friends. Unfortunately for Shane, his friends chose that night to steal a Mustang. “I sat and watched them strip it right there on the street,” he says. immediately realizing the money he could make, Shane started down the path that led to his career in vehicular theft. In just three years, he claims to have stolen more than 500 bikes. Not bad, considering insurance industry estimates suggest more than 30,000 bikes are stolen every year in the United States. In California alone, 8203 bikes were stolen in 1994, according to the California Highway Patrol.

But before any of those bikes could be stolen, they first had to be located. And that’s where Shane came in. He discovered he could earn a hefty “finder’s fee” for merely scouting out vehicles. “I started immediately because I was desperate,” he says. “I wanted my son back, I wanted to stay in school and I didn't want to be homeless.”

So Shane cruised apartment complexes for likely cars. Then he discovered sportbikes-Suzuki GSX-Rs, to be exact.

Shane’s sportbike single-mindedness is common. In fact, most bike thieves tend to be vehicle-type specific. According to Detective Joe Thrasher of the Orange County (California) Auto Theft Task Force, “Most crooks have an idea of what kind of bike they like to deal with, because they have access to parts or whatever.”

But brands and models aside, Thrasher and Shane agree that when it comes to motorcycle theft, there are two main categories: theft for order and spontaneous theft.

Theft for order is exactly what it sounds like. A buyer requests a particular bike and, around midnight, thieves cruise apartment complexes until they find the desired model. A pretty typical scenario, according to Detective Thrasher. “We’re finding out crooks tend to steal motorcycles out of large apartment or condominium complexes.

Some of them were even gated, but the thieves just scaled the walls,” he says. Other targeted areas include military bases and college campuses because of the open, poorly lit parking. For Shane, however, apartment complexes proved the most profitable. “First, you drive up to the bike and observe,” he explains. “You’re not legally doing anything wrong. You’re not prowling, you’re not vehicle tampering, there’s no tools on you...if the bike has a lock, you analyze it...then, you come back.”

The return trip is more complicated because tools are required. Often bikes are armed with locks or alarms, which can hinder a thief. But Shane says a large pair of bolt-cutters can make short shrift of any lock, and that mastering most alarms is as simple as snipping wires. Explains Shane, “If you know what you’re doing, you can do it in less than a minute.” And after defeating an alarm or lock, Shane says it’s just a matter of popping out the ignition, starting the bike and riding away. Detective Eric Wiseman, who worked with Thrasher on a case that resulted in seven arrests and more than 100 recovered bikes, claims alarms aren’t very effective.

“I can think of at least four bikes in our case which were alarmed and it had minimal or no effect on the bikes being stolen,” says Wiseman. “And I've talked to people who had three locks on their bike and a parked car against it so the suspects had to physically lift the motorcycle over the car to get it out. If thieves want the motorcycle, they can get it.” Obviously there are no fool-proof methods for theft prevention, but Shane maintains that deterrents and cautious behavior can lessen the chances for thievery. He suggests an alarm and a disc lock, adding that if apartment complex parking is necessary, do so in a busy area. He says, “I kept my bike from getting stolen by practically pushing it into my bedroom.”

The detectives concur. “I would say that if someone is going to buy an alarm, buy one with some type of killswitch,” Wiseman advises. Adds Thrasher, “Lock the bike and garage it. Even in your garage, you need a lock.”

This remains true when it comes to spontaneous theft, which usually occurs when thieves have nothing better to do. For example, Shane was returning home from a movie one night when he spotted an unlocked bike that was armed with just a front-disc lock. He went home for his tools and a replacement wheel, returned and took the bike. A pretty profitable evening, considering he only set out to see a film.

It was this sort of observant behavior that made Shane such a popular thief. “No matter what,” he says, “I could always get (buyers) what they wanted. I was a man of action. They had great respect for me because they knew I had balls and that I did my own dirty work.”

Shane says, however, that he only was involved with the stolen bikes until he delivered them to his regular customers. “I never wanted to know what they did,” he emphasizes about his buyers. “Sometimes they wanted the bikes in pieces and sometimes whole, so I guessed they were changing Vehicle Identification Numbers (VINs).”

Altering VINs is a fairly common practice among thieves, says Wiseman. “The suspects are sophisticated,” he explains.

“They’re altering numbers and they’re able to obtain title and registration legitimately through the Department of Motor Vehicles.”

For example, one of Wiseman’s recent cases involved suspects who bought titled salvage frames, rebuilt the bikes with stolen parts and sold them to dealerships and individuals. “With these bikes, you have a legitimate motorcycle frame, so when the suspect sells it there is a clear title,” he says. “The remaining parts are stolen, but the frame is legitimately owned by whoever bought it.”

For Shane, this type of situation was very profitable; at one point he grossed more than $30,000 in just three months of stealing bikes. His going rate was approximately $800 for a whole bike and $1200 for a parted-out one. His lifestyle took a decided turn for the better.

“We’re talking six bikes, three cars, a new mountain bike, a laptop computer, TVs, VCRs, video cameras-everything

brand new, top-of-the-line. Those were my ill-begotten gains,” he says.

At this point, ironically, Shane was arrested for helping a friend steal a bike. The police caught the friend red-handed and found Shane in the fellow’s car. “They arrested me for auto theft because I dropped him off and I knew he was going to steal the bike,” says Shane. But he made a deal with the state and served only five months at Elmwood Correctional Facility.

“It was a minimum-security camp, so jail was a joke,” he laughs. “It wasn’t hard time at all. There is nothing there to learn and you only get into more trouble than you started with. You find there’s smarter people than you behind the walls and they have every answer to everywhere you screwed up. It just makes you a better criminal.”

Indeed, it was in jail that Shane learned the value of parting-out bikes. “When you rebuild wrecked bikes with stolen parts, it’s too easy to get caught,” he says.

With that lesson in mind, Shane sold stolen components and used the profits to buy legitimate parts to rebuild bikes.

And, then, he just stopped.

“I finally quit stealing because everywhere I went, somebody expected something from me,” he says. “They were like beggars, and if I couldn’t get them what they wanted, they were mad at me.”

Shane maintains, however, that he didn’t quit stealing because of his conscience. When he took a bike, he says the owner was “out of sight, out of mind...all you see is this material object...and there is always

that one element of not getting caught that compels you to do it again. You’ll do it again and again until eventually you do get caught. But you don’t feel bad, you were born to steal.”

Following Shane’s “retirement,” he attempted to walk the straight-and-narrow. Unfortunately, he tripped. “I went for a ride, knowing I didn’t have a driver’s license and knowing that if I got stopped they would arrest me,” he says.

Sure enough, following a 150-mph-plus chase through the hills of Northern California, he was apprehended for evading arrest. Because of Shane’s prior record, he faced 16 months in California State Prison, San Quentin. Instead, & Shane says he volunteered and was selected for an alternative sentencing program called “Boot Camp” offered by the state of California.

Unlike Shane’s previous jail time, the military-esque Boot Camp was a positive learning experience. “They teach you to restructure your life, realize your mistakes, confront them, overcome them and learn to be a more productive citizen,”

he explains.

Shane insists he has taken these lessons to heart. Right now, he has a data-entry job in San Jose, lives in Oakland and gets off parole in March.

Sitting at the playground picnic table, Shane smiles because he believes his future looks promising. He watches the sun sink below the treetops, and as the shadows begin to lengthen, the last of the children go home, leaving only empty swings swaying in the warm breeze.

And as Shane gets up and walks away, he doesn’t seem sinister or intimidating at all. □Q

“I WAS A MAN OF ACTION. I HAD BALLS AND I DID MY OWN DIRTY WORK.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

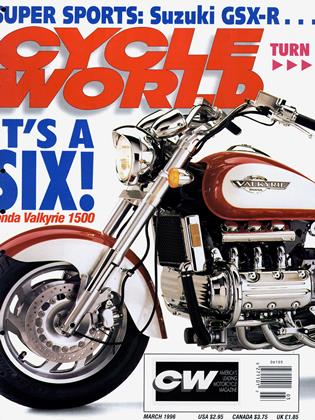

Up Front

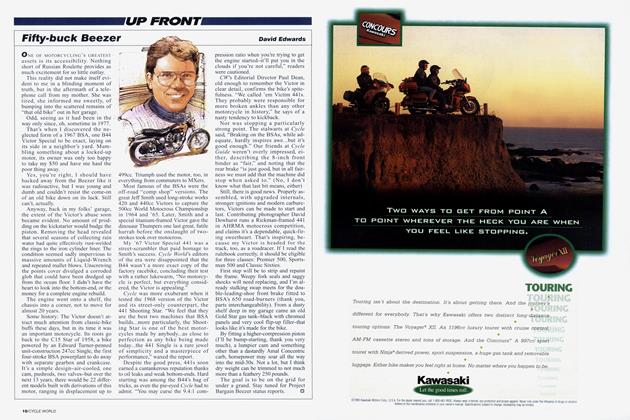

Up FrontFifty-Buck Beezer

March 1996 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOur Brother's Keeper

March 1996 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTorque Shows

March 1996 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1996 -

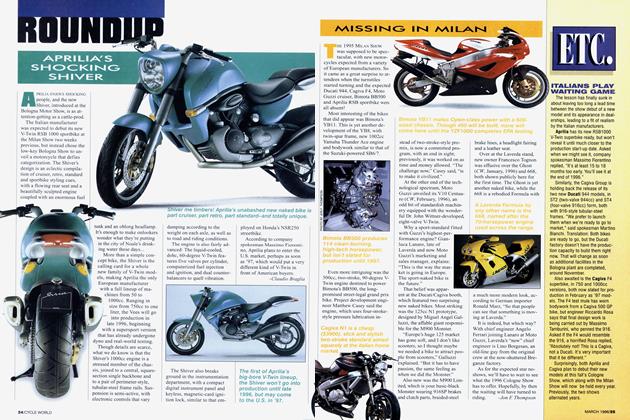

Roundup

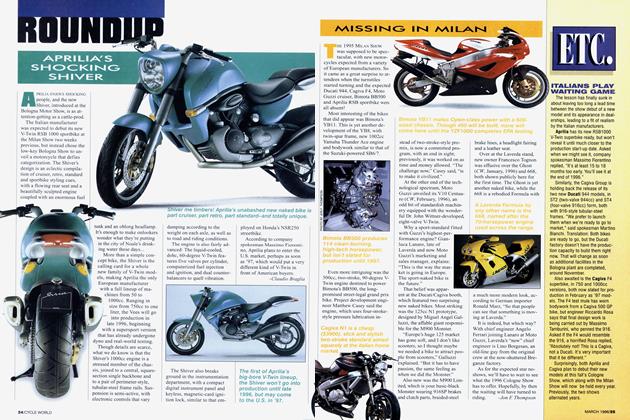

RoundupAprilia's Shocking Shiver

March 1996 By Claudio Braglia -

Roundup

RoundupMissing In Milan

March 1996 By Jon F. Thompson