Vietnam Experience

Riding through a once-notorious land

SAM MITANI

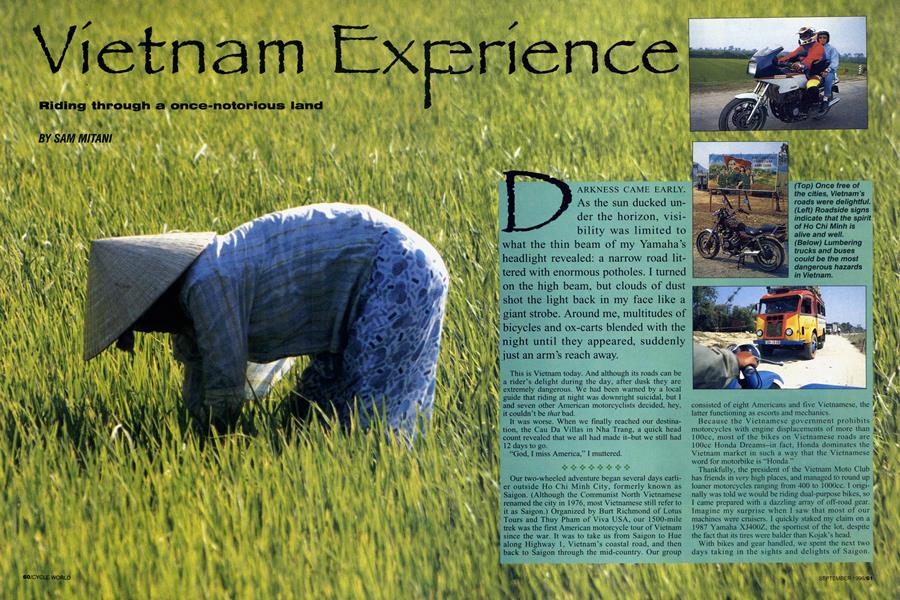

DARKNESS CAME EARLY. As the sun ducked under the horizon, visibility was limited to what the thin beam of my Yamaha’s headlight revealed: a narrow road littered with enormous potholes. I turned on the high beam, but clouds of dust shot the light back in my face like a giant strobe. Around me, multitudes of bicycles and ox-carts blended with the night until they appeared, suddenly just an arm’s reach away.

This is Vietnam today. And although its roads can be a rider’s delight during the day, after dusk they are extremely dangerous. We had been warned by a local guide that riding at night was downright suicidal, but I and seven other American motorcyclists decided, hey, it couldn’t be that bad.

It was worse. When we finally reached our destination, the Cau Da Villas in Nha Trang, a quick head count revealed that we all had made it-but we still had 12 days to go.

“God, I miss America,” I muttered.

Our two-wheeled adventure began several days earlier outside Ho Chi Minh City, formerly known as Saigon. (Although the Communist North Vietnamese renamed the city in 1976, most Vietnamese still refer to it as Saigon.) Organized by Burt Richmond of Lotus Tours and Thuy Pham of Viva USA, our 1500-mile trek was the first American motorcycle tour of Vietnam since the war. It was to take us from Saigon to Hue along Highway 1, Vietnam’s coastal road, and then back to Saigon through the mid-country. Our group

consisted of eight Americans and five Vietnamese, the latter functioning as escorts and mechanics.

Because the Vietnamese government prohibits motorcycles with engine displacements of more than lOOcc, most of the bikes on Vietnamese roads are lOOcc Honda Dreams-in fact, Honda dominates the Vietnam market in such a way that the Vietnamese word for motorbike is “Honda.”

Thankfully, the president of the Vietnam Moto Club has friends in very high places, and managed to round up loaner motorcycles ranging from 400 to lOOOcc. I originally was told we would be riding dual-purpose bikes, so I came prepared with a dazzling array of off-road gear. Imagine my surprise when I saw that most of our machines were cruisers. I quickly staked my claim on a 1987 Yamaha XJ400Z, the sportiest of the lot, despite the fact that its tires were balder than Kojak’s head.

With bikes and gear handled, we spent the next two days taking in the sights and delights of Saigon.

Unfortunately, I took in a little more than I bargained for. The morning we planned to embark on our 14-day journey, the others were as excited as Boy Scouts on their first day of camp. I, on the other hand, awoke with what would be dubbed the Vietnam Death Virus.

Apparently, I had eaten some bad shrimp, which was wreaking havoc with my internal organs. Symptoms included severe diarrhea and sporadic, intense stomach cramps that often left me doubled over and short of breath.

Although the VDV stayed with me throughout most of the trip, it varied in intensity. Sometimes I simply felt queasy, at other times a high-grade fever was thrown into the mix. Sipping tea for supper one evening for fear of exacerbating the virus, I whispered to myself, “God, I miss America.”

Despite my gastrointestinal predicament, the tour progressed on schedule. Unfortunately, five minutes into the first day’s ride one tour participant’s 1986 Yamaha 750 experienced electrical difficulties. It was obvious that our mounts were far from being in prime condition. Nevertheless, the mechanics fixed the problem in minutes. Throughout the trip, our mechanics, bringing up the rear in a time-worn Russian Ural sidecar, overcame every obstacle we encountered-seemingly with no tools or proper parts.

We continued on Highway 1 to our first day’s destination. This stretch of coastal road proved to be a formidable challenge: We dodged countless mopeds, pedestrians, trucks and buses. We arrived safely, however, and after a good night’s sleep were ready for our second day. We were greeted by a hot sun, clear skies and wonderfully improved roads. Not only was the tarmac much smoother, but traffic was significantly less hazardous.

Three hours into the ride, we stopped near a small village inhabited by a group of people called the Cham, best described as the aborigines of Vietnam. One seemed to ask if we were interested in visiting his village, which we inferred was only a mile away. We thought he said there was a temple there. Our intrepid

team was pointed toward a crude dirt trail of deep, soft sand. My bike slid almost uncontrollably and I clung to the handlebar like a rodeo bull-rider. This slipping and sliding continued for an entire mile...then for 2, then for 10. Obviously, there had been a communication breakdown with our Cham guide.

Fifteen miles later, we reached the village. We were immediately surrounded by about 100 curious onlookers, mostly children, who acted as if they had never seen Americans-and they probably hadn’t.

Unfortunately, we saw no temple so we bid farewell to the Cham and hurried back to civilization. When we returned to the main road, the mechanics were waiting for us, and we rode to our lunch destination.

We were more than three hours behind schedule, which was why we wound up riding to Nha Trang after dark-at the time totally oblivious to the dangers that awaited us after the sun went down.

Having made it through the night relatively unscathed, we spent the next day sightseeing in the beautiful fishing community of Nha Trang, which was once the favorite seaside retreat of Emperor Bao Dai. We spent the day relaxing, sunbathing and scuba diving before leaving the picturesque village.

The next stop was Da Nang, where we climbed the Marble Mountains, a series of five marble-and-limestone peaks that were a Viet Cong stronghold during the war. For one tour member, this was his second Vietnam experience. Ed Davis was stationed near the city more than 25 years ago, serving with the Marine Corps. I asked him how it felt to return to this once-hostile place.

He reflected for a long moment, searching for the right words. Finally, he answered by simply saying, “Weird.”

When we descended the mountains, we dodged Da Nang’s persistent peddlers, who were selling everything from postcards to statuettes, and were back on our bikes and headed for Hue.

The quality of the road had deteriorated somewhat, but traffic remained relatively light. For the first time, I felt at peace: The countryside was lovely and the bike was running well. Then I came upon a slow-moving bus.

I anticipated no problems in overtaking this mammoth until, halfway through the maneuver, the bus suddenly veered left. I honked my horn like a New York cabbie, but the bus kept coming. My only escape route, the left shoulder, was obstructed by a large pile of boulders.

I was left with three options: 1) Steer left on to the soft dirt shoulder and hope I could stop the bike before colliding with the boulders; 2) steer farther left, avoiding the rocks altogether, but risking the uncertainties of a large drop-off; or 3) stay on the road and pray the bus driver noticed me before pancaking me into the tarmac.

I chose Option One. Just as the bus made contact with the Yamaha, I swung the bike left. When the tires hit the dirt shoulder, the motorcycle slid sideways. I managed to catch it before losing control, but as I got on the brakes, the wheels locked. I braced for impact. Thud! My front tire smashed into the rocks, and the jolt sent the rear end airborne, but somehow I avoided being flung from the bike or falling over.

My first reaction was to flash the bus driver an unfriendly American hand gesture, but I decided against it. He drove on, oblivious. I shook my head and muttered, “God, I miss America.”

We eventually made our way to Hue, which signified the halfway point of our tour. Like Saigon, Hue was a bustling metropolis, its streets overflowing with scooters and pedestrians. We only stayed the night, and the following day headed for Pleiku, the site of an American Army base that suffered a terrible shelling by the Viet Cong. Today, Pleiku is a peaceful market town of about 40,000 people haunted no longer by the ghosts of war.

Pleiku also placed us on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, once the main thoroughfare for the Viet Cong’s troops and supplies. Now, the infamous trail meanders innocently through the mid-country, where life is more primitive than in the south, evidenced by the

many houses made from wood or straw-though some had television antennas strapped to the roofs. There were also fewer motor-driven vehicles. Traffic consisted primarily of bicycles and ox-carts.

After leaving Pleiku, we rode on to Ban Me Thuot, where we took time for elephant rides.

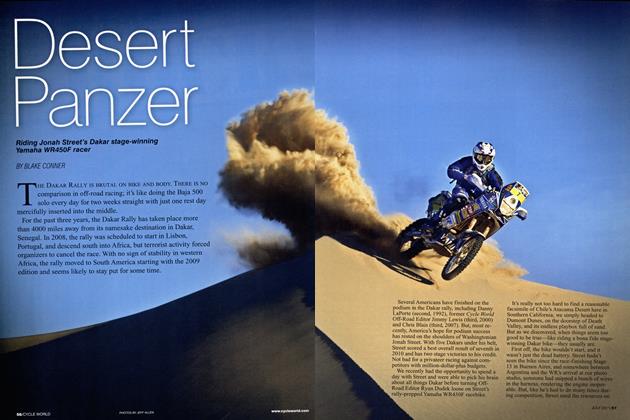

The next day, we set off for Da Lat, a quaint town that sits 4500 feet above sea level. The road there was actually a dirt trail so adverse that most public vehicles avoid it. Still, the countryside was magnificent. We were surrounded by blue mountains and small rivers. I opened up the Yamaha’s throttle, and reveled at the beauty of the moment, living my own version of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Before long we reached Da Lat, where we dined in a wonderful restaurant.

The following morning, however, the mood had turned somber. We had come to the final leg of the trip. The day’s ride back to Saigon was relatively uneventful, and we reached the city’s borders with rush hour in full swing. Trying to describe the traffic is impossible: It must be seen to be believed. I nearly took out one bicyclist, two pedestrians, a half dozen trucks and two dogs.

That evening, the “First American Motorcycle Tour of Vietnam Since the War” officially came to an end. We exchanged addresses and said our goodbyes, congratulating each other on surviving the trip.

Although I slept most of the 13hour plane trip home, I awoke to peer out the window at Los Angeles materializing below. Usually at a trip’s end, I’m overcome with joy at being home. But this time, I was filled with sadness. Before the Boeing 747 had lowered its landing gear, I found myself uttering, “God, I miss Vietnam.” E3

Sam Mitani is Associate Editor for Road & Track magazine. For more information about touring Vietnam, contact Viva USA at 714/972-2248 or Lotus Tours at 312/951-0031.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue