UP FRONT

Seca Sunday

David Edwards

ABOUT ONCE A MONTH, IT SEEMS, I GET a phone call. “You own a Seca 650, right?” a disembodied voice on the other end of the line asks.

“I do.”

“Uh, you interested in selling it?”

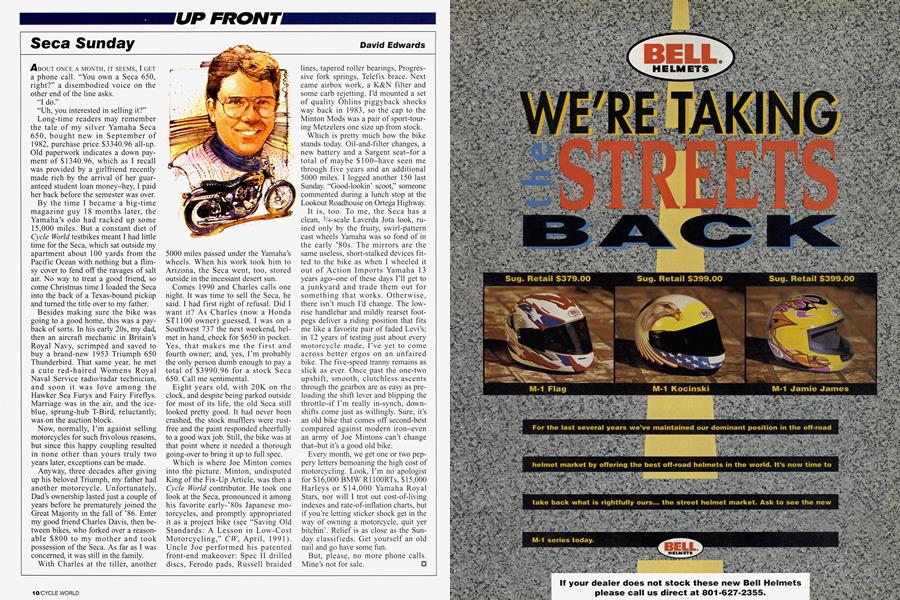

Long-time readers may remember the tale of my silver Yamaha Seca 650, bought new in September of 1982, purchase price $3340.96 all-up. Old paperwork indicates a down payment of $1340.96, which as I recall was provided by a girlfriend recently made rich by the arrival of her guaranteed student loan money-hey, I paid her back before the semester was over.

By the time I became a big-time magazine guy 18 months later, the Yamaha’s odo had racked up some 15,000 miles. But a constant diet of Cycle World testbikes meant I had little time for the Seca, which sat outside my apartment about 100 yards from the Pacific Ocean with nothing but a flimsy cover to fend off the ravages of salt air. No way to treat a good friend, so come Christmas time I loaded the Seca into the back of a Texas-bound pickup and turned the title over to my father.

Besides making sure the bike was going to a good home, this was a payback of sorts. In his early 20s, my dad, then an aircraft mechanic in Britain’s Royal Navy, scrimped and saved to buy a brand-new 1953 Triumph 650 Thunderbird. That same year, he met a cute red-haired Womens Royal Naval Service radio/radar technician, and soon it was love among the Hawker Sea Furys and Fairy Fireflys. Marriage was in the air, and the iceblue, sprung-hub T-Bird, reluctantly, was on the auction block.

Now, normally, I’m against selling motorcycles for such frivolous reasons, but since this happy coupling resulted in none other than yours truly two years later, exceptions can be made.

Anyway, three decades after giving up his beloved Triumph, my father had another motorcycle. Unfortunately, Dad’s ownership lasted just a couple of years before he prematurely joined the Great Majority in the fall of ’86. Enter my good friend Charles Davis, then between bikes, who forked over a reasonable $800 to my mother and took possession of the Seca. As far as I was concerned, it was still in the family.

With Charles at the tiller, another 5000 miles passed under the Yamaha’s wheels. When his work took him to Arizona, the Seca went, too, stored outside in the incessant desert sun.

Comes 1990 and Charles calls one night. It was time to sell the Seca, he said. I had first right of refusal. Did I want it? As Charles (now a Honda ST 1100 owner) guessed, I was on a Southwest 737 the next weekend, helmet in hand, check for $650 in pocket. Yes, that makes me the first and fourth owner; and, yes, I’m probably the only person dumb enough to pay a total of $3990.96 for a stock Seca 650. Call me sentimental.

Eight years old, with 20K on the clock, and despite being parked outside for most of its life, the old Seca still looked pretty good. It had never been crashed, the stock mufflers were rustfree and the paint responded cheerfully to a good wax job. Still, the bike was at that point where it needed a thorough going-over to bring it up to full spec.

Which is where Joe Minton comes into the picture. Minton, undisputed King of the Fix-Up Article, was then a Cycle World contributor. He took one look at the Seca, pronounced it among his favorite early-’80s Japanese motorcycles, and promptly appropriated it as a project bike (see “Saving Old Standards: A Lesson in Low-Cost Motorcycling,” CW, April, 1991). Uncle Joe performed his patented front-end makeover: Spec II drilled discs, Ferodo pads, Russell braided lines, tapered roller bearings, Progressive fork springs, Telefix brace. Next came airbox work, a K&N filter and some carb rejetting. I’d mounted a set of quality Öhlins piggyback shocks way back in 1983, so the cap to the Minton Mods was a pair of sport-touring Metzelers one size up from stock.

Which is pretty much how the bike stands today. Oil-and-filter changes, a new battery and a Sargent seat-for a total of maybe $ 100-have seen me through five years and an additional 5000 miles. I logged another 150 last Sunday. “Good-lookin’ scoot,” someone commented during a lunch stop at the Lookout Roadhouse on Ortega Highway.

It is, too. To me, the Seca has a clean, 3/4-scale Laverda Jota look, ruined only by the fruity, swirl-pattern cast wheels Yamaha was so fond of in the early ’80s. The mirrors are the same useless, short-stalked devices fitted to the bike as when I wheeled it out of Action Imports Yamaha 13 years ago-one of these days I’ll get to a junkyard and trade them out for something that works. Otherwise, there isn’t much I’d change. The lowrise handlebar and mildly rearset footpegs deliver a riding position that fits me like a favorite pair of faded Levi’s; in 12 years of testing just about every motorcycle made, I’ve yet to come across better ergos on an unfaired bike. The five-speed tranny remains as slick as ever. Once past the one-two upshift, smooth, clutchless ascents through the gearbox are as easy as preloading the shift lever and blipping the throttle-if I’m really in-synch, downshifts come just as willingly. Sure, it’s an old bike that comes off second-best compared against modern iron-even an army of Joe Mintons can’t change that-but it’s a good old bike.

Every month, we get one or two peppery letters bemoaning the high cost of motorcycling. Look, I’m no apologist for $16,000 BMW R1 lOORTs, $15,000 Harleys or $14,000 Yamaha Royal Stars, nor will I trot out cost-of-living indexes and rate-of-inflation charts, but if you’re letting sticker shock get in the way of owning a motorcycle, quit yer bitchin’. Relief is as close as the Sunday classifieds. Get yourself an old nail and go have some fun.

But, please, no more phone calls. Mine’s not for sale. □