SERVICE

Paul Dean

A Heli of a deal

I’m a new Honda VFR750 owner, ’94 model, and I need some advice. At 6-foot-3 and 210 pounds, I get antsy after anything more than 100 miles on the VFR. Time to get off and stretch a little. I recently received some information on Heli Manufacturing’s taller replacement handlebars, and they seem logical, although $208 is a bit pricey. If you guys have done any tests of these bars on a VFR750 or have even ridden one with them installed, please tell me what you think. I’m torn between replacing the bars and replacing the seat. A nice Corbin is more money, but my rear end would be very thankful.

Ike Nissen

Farmington, New Mexico

/ suggest that you not change the seat and the handlebars at the same time; buy one of the two first and determine its ergonomic impact on your VFR before purchasing the other And because the Heli VFR bars are made only in one shape, 14/U/C (Iorhin can offer so~ne de gree of variation and custom -tailoring in a seat, the handlebars ought to come first. Once you know how they afj~ct your riding c'omfirt, you `Ii have a bet ter idea of what you need in a seat.

We have indeed used He/i bars on a VFR 750, though it was a 1992 model. The bar-to-seat relationship on the `90`93 models is almost identical to those of the `94`95 versions, though, so our findings are valid Jbr your bike.

For the most part, we felt the Helis did improve the VFR s long-range comfort. They propped the torso more upright, thereby easing the load on wrists and forearms, and they allowed taller riders in particular to ride longer on the open road with less discomfort.

But there are some compromises. So that the hand controls will still notch into the cutouts on the sides of the fairing at full steering lock, the higher-rise Helis have to be made with a handgrip angle that’s not epate as natural as that of the stock bars. And because the Helis sit you more upright, you have to fight the wind much more actively as it tries to blow your torso backward at higher speeds. You usually can overcome this bv crouching into a tuck, but that defeats the reason for switching to higher bars. Despite that, we still liked the Helis for most riding other than sustained higher speeds on the open road.

For the Seca stability

I have a 1992 Yamaha Seca II that handles really well in most twisties, but it’s not very confidence-inspiring in the high-speed sweepers. It feels like it would fly off the outside of the turn if 1 were to try even the slightest mid-course correction.

In attempting to give the Seca a more firmly planted feel, I have installed Comp K Metzeler tires and replaced the stock front fork springs with a set from Progressive Suspension. These changes have given the bike more stability in the turns, but not enough. Can you offer me any ideas for improvement in this area?

Richard DiGrazia Albany, California

We're very familiar with this bike's h igh-speed h andli ng sh or t com ings, having addressed them in a Seca II project story in our December, 1993, issue. We switched to Comp K tires and Progressive fork springs, too, but we effected a major handling improvement bv replacing the stock rear shock with one of Progressive’s Adaptive units. It will set you back $395, but it gets the job done rather nicely, particularly for street use. We roadraced our Seca II after completion and found that the suspension even performed surprisingly well under the demanding conditions of competition.

lie also made a few other fork modifications that improved high-speed handling. The springs we used were Progressive :~ FZR 600 replace~nen ts, preloaded with 11 `/16-inch-long spac ers made o/PLC tubing. U~ also had Progressi e perfortn an S~5 n odiflca -tion on the fork damper Y)dS, then set the fork oil level to 6 inches from the top of' the tubes (`stock is 4.4 inches) using /5/20-weight Be/-Ray fOrk oil.

Shims vs. shams

I’d like to know why all the motorcycle manufacturers make their highpowered bikes with engines that have shim-adjusted valves. What advantages does the shim design have over the threaded style of valve adjusters? Thanks to shims, the average motorcycle owner no longer can adjust his or her bike’s valves. The manufacturers don’t use shims to generate more business in labor and parts for the dealers, do they? Richard E. Taylor

Surrey, British Columbia, Canada

The reasons for the widespread use of shim-adjusted valves in high-performance motorcycle engines have nothing to do with dealer income and everything to do with making those engines more efficient.

To begin with, shim-type adjusters require fewer and/or smaller components than do threaded adjusters, which must be used with cam followers or rocker arms of some kind. Shim systems therefore allow the valve train to be lighter, which, in high-output, high-revving engines, means reduced valve-train inertia. Less inertia permits an engine to spin at higher rpm before the valves start to float.

Shim-type adjusters also allow much longer intervals between valve adjustments. Shim systems have just one high-wear area (between cam lobe and shim or shim bucket), and they distribute the extremely high loads of valve-spring pressure across the entire width of the lobe. Screw adjusters, on the other hand, have two high-wear areas (one between cam and follower, another between adjuster and valve). Worse yet, the spring-pressure loads at the tip of the adjuster screw are concentrated in one small area, resulting in a higher rate of wear

Shim adjusters, incidentally, are not an invention of the motorcycle industry; this method of valve adjustment was used for decades in high-performance automobile engines, mostly of European origin, before being adopted by motorcycle designers. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

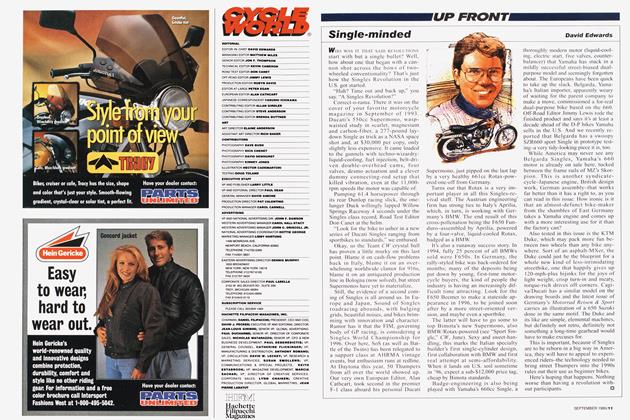

Up Front

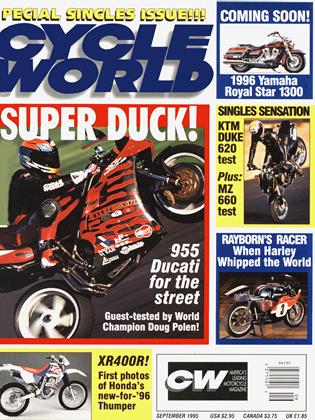

Up FrontSingle-Minded

September 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Bikes of Lago Di Como

September 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCIllusion, Disillusion

September 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsLetters

September 1995 -

Roundup

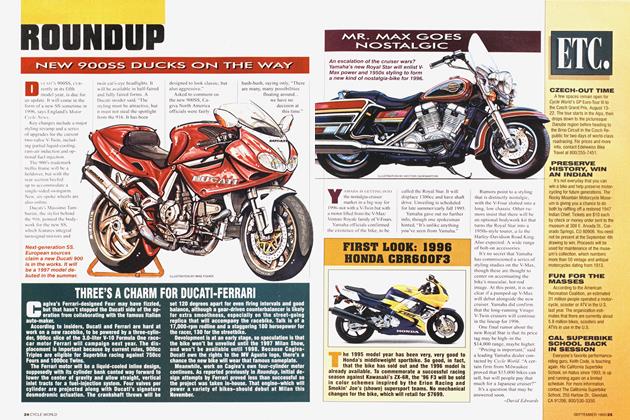

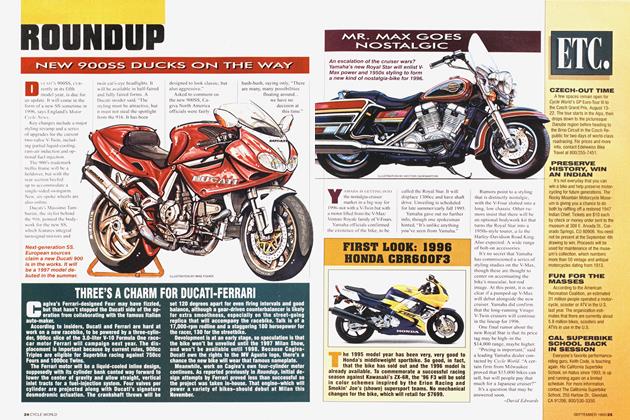

RoundupNew 900ss Ducks On the Way

September 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupThree's A Charm For Ducati-Ferrari

September 1995