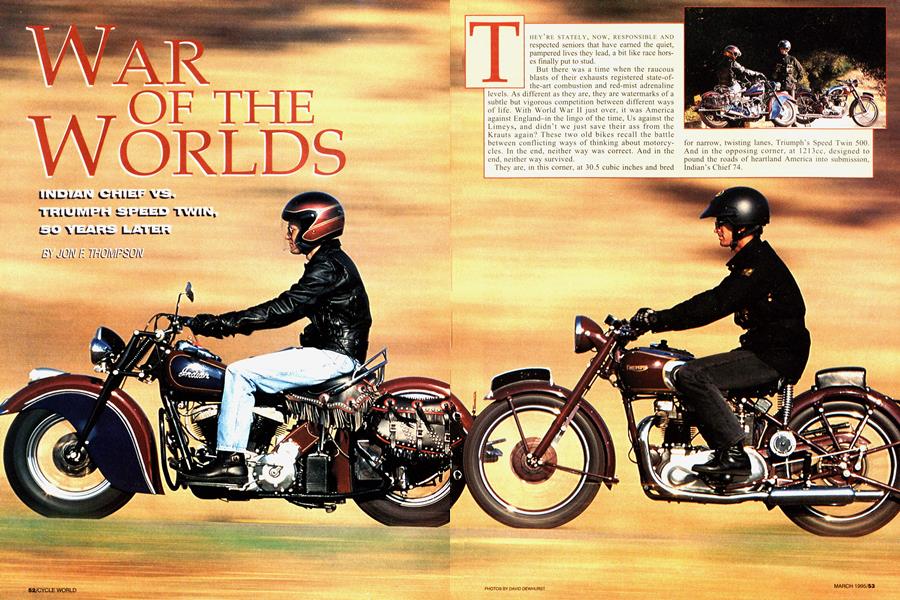

WAR OF THE WORLDS

INDIAN CHIEF VS. TRIUMPH SPEED TWIN, 50 YEARS LATER

F. THOMPSON

THEY’RE STATELY, NOW, RESPONSIBLE AND respected seniors that have earned the quiet, pampered lives they lead, a bit like race horses finally put to stud.

But there was a time when the raucous blasts of their exhausts registered state-of-the-art combustion and red-mist adrenaline levels. As different as they are, they are watermarks of a subtle but vigorous competition between different ways of life. With World War II just over, it was America against England-in the lingo of the time, Us against the Limeys, and didn’t we just save their ass from the Krauts again? These two old bikes recall the battle between conflicting ways of thinking about motorcycles. In the end, neither way was correct. And in the end, neither way survived.

They are, in this corner, at 30.5 cubic inches and bred for narrow, twisting lanes, Triumph’s Speed Twin 500. And in the opposing corner, at 1213cc, designed to pound the roads of heartland America into submission, Indian’s Chief 74.

Obviously a mismatch, a flyweight against a heavyweight. But maybe not. For while the Indian had tradition and established practice on its side, a good part of Triumph’s design was based on a reluctant willingness to push the edges of the technological envelope.

The result is hardware with history, motorcycles from robust and respected family trees, one at the end of its development cycle, the other at the beginning. Both branched from companies that began in the twilight of this century, with roots in the very beginning of an age that led to mechanization and inexpensive, reliable transportation for everyone. now Europe had been quiet for more than a year and combatants everywhere were digging themselves out of war footing, blinking at the thunderous silence of peace, and looking for diversion. Indian and Triumph, having lent their facilities for production of war materiel, once again were cranking out civilian equipment. Indian began building 74-cubic-inch Chiefs in 1923, with what Indian historian Jerry Hatfield calls, “All the technical wizardry of old lawn mowers.” Indian restoration expert Wilson Plank, of American Indian Specialists, in Fullerton, California, who services our test Indian for its owner, traces the engine to the 1920 G20, which debuted a list of features that quickly became articles of the Indian faith. The list includes the first cast-alloy primary-drive cover, the first time a transmission was bolted to the engine cases to form what was called semi-unit construction, and the first time a primary case contained its own oil bath.

It was an interesting year, 1947, the year these two bikes were built, a year straining with dynamic portents. British driver John Cobb went 394 mph at Bonneville in the Railton-Mobil. Chuck Yeager blasted over Edwards Air Force Base faster than the speed of sound. And both Henry Ford and Ettore Bugatti-two other men interested, in their own ways, in speed-died. By

Indian had been in business since 1901, established in Springfield, Massachusetts, by Carl Oscar Hcdstrom and George W. Hendee as the Hendee Manufacturing Company. In its early years, Indian was a wellspring of technological achievement, showing such fitments as rear suspension and electric starting as early as 1914. The company was performance-oriented, and raced anywhere there was competition, winning both the Isle of Man and the Belgian Grand Prix in 1923, both times with Freddie Dixon up. But by 1916, under strong competitive pressure from Harley-Davidson and at cross-purposes with his board of directors, Hendee, the last of the original company’s guiding lights resignedfollowing the example of Hedstrom, who departed in 1913. Indian rumbled along for a while between peaks of success and valleys of economic difficulty, then went into a long, slow decline that finally ended in 1953.

The evolutionary line of the G20, Plank says, leads straight to the 1947 74s and later 80-cubic-inch Chiefs.

These are simple engines, 42-degree dry-sump V-Twins. They use massively undersquare engine dimensions, with bore/stroke measurements of 3 1/4x4 7/16 inches. That long stroke operates on single-throw cranks that give the bikes their characteristic arrhythmic VTwin heartbeat. They drive through a foot-operated clutch and simple, handshifted, three-speed transmissions.

Frame and suspension are as elemental as the engine. The frame, described by Indian as a “spring frame,” used a single backbone and twin lower loops to carry the semi-unit engine and transmission. Two more loops formed a rear subframe to carry a pair of suspension plungers-springs only, no dampinghence the “spring frame” designation, which Indian began offering in 1940.

Up front, at least for 1947, Indian stuck with a sprung girder fork.

By this time much of this had been echoed, and even improved upon, by Harley-Davidson. What gave this line of Chiefs its special charisma, at least from our perspective today, was their heavily valanced fenders, art-deco elements introduced on 1940 models that make these bikes instantly recognizable.

The Speed Twin, meanwhile, came from a company founded in England in 1897 by Siegfried Bettmann and Maurice Schulte to build bicycles. The pair began building motorcycles in 1903 and quickly established a reputation for quality and performance. The company grew, then nearly died in the general depression of the early 1930s. That was when it came under the control of industrialist Jack Sangster, who owned the Ariel plant in Birmingham. Sangster put Edward Turner, his chief designer, in charge of Triumph’s Coventry works. Turner responded to the challenge in 1938 by introducing the Speed Twin, said by some to be based upon an earlier Val Page design. The Speed Twin became the root of Triumph’s post-war family tree. It was important for another reason. It became one piece of the puzzle designed to bring foreign money into England, which needed cash to rebuild from the devastation of war-through a nasty trick of politics and fate, England was not a recipient of Marshall Plan funding aimed at rebuilding war-ravaged Continental countries.

With the exception of its telescopic fork-the original versions used girder forks-the bike you see here is almost identical to its 1938 counterpart, and is close, in evolutionary terms, to the machines that would follow it. Consider, for instance, the engine. Though eventually it would be enlarged to 750cc, in its basic form its bore and stroke measured 63 x 80mm to produce 498cc. It uses a 360-degree crank, so the pistons rise and fall in tandem and fire alternatively. Its two overhead valves per cylinder are pushrodactuated by twin cams that reside high in the crankcase, the exhaust cam ahead of, and the intake cam behind, the crank centerline. This willing little engine, delicate and beautifully made in comparison to the blacksmithy nature of the Indian engine, drew on the notion that rpm equals horsepower. So applied to the Cycle World dynomometer 48 years after its manufacture, the Triumph produced 18 peak rear-wheel horsepower, while the Chief, with an engine more than twice as large as the Triumph’s, but turning much more slowly, and with a flat-head, side-valve design, produced 24-more, but not much more.

In terms of technology, then, the Triumph’s engine was far ahead of the Indian’s, right down to the comparative beauty of its castings. So was its gearbox, which is driven by an oil-bath, multi-plate clutch. The transmission is a four-speed unit that is, like the Indian’s, without synchromesh. But where the Indian transmission is without detents and is shifted with the right hand, the Triumph’s is sequential and is shifted with the right foot in the classic one-down, three-up pattern.

It is bolted to the bike’s very basic frame. This comprises a single backbone and a single downtube, with a pair of lower fore-aft runners and a rear, bolt-on subframe innocent of any sort of suspension except that provided by the flexing of the rear tire’s sidewall.

It is a much smaller bike than the Indian, and after riding the American bike, with its open, roomy riding position and wide reach to the handlebar, the Triumph feels tight and cramped.

The differences between these two bikes are far more profound than that. These bikes may have been built the same year, but the Chief has its roots in the past while the Speed Twin is looking toward tomorrow’s horizon. The differences become evident as soon as you begin executing their respective starting drills.

The Triumph is easy. Pull open the fuel tap, hold down the tickler until the float bowl overflows, then apply muscle and bootleather to the kickstart lever, and do it hard enough that the bike's magneto spins fast enough to supply a strong spark to the plugs. The bike fires right up and immediately settles into a staccato idle.

Starting the Indian is much more complex, and is made more complex still by the fact that this example’s throttle is operated by the left twistgrip. This was optional-Indians could be set up with leftor right-hand throttles. This bike’s start drill goes like this: Fuel taps, both of them, on; the Linken carb’s choke to full-on position; roll the throttle off, and roll the spark advance, operated by the right-hand twistgrip, to full retard; using the bike's very industrial kickstart lever, fill the cylinders with mixture by booting the engine through two intake strokes; move the choke lever to one notch from full off, switch on the key; gently roll down on the kickstarter until the ammeter gives a twitch; jump on the kickstarter with all the energy you possess. If it doesn’t start, kick it again. If it still doesn’t start, kick it again, this time with a bit of throttle. As soon as the massive engine does rumble to life, roll the right grip to full advance, and leave it there until you have to perform the start drill again.

So, once both of these antique engines alight, your troubles are over? They are with the Triumph. Just pull in the clutch lever, select first, gas it and go. Aboard the Indian—owned, like the Triumph, by Los Angeles architect and collector Lucian Hood, and loaned to Cycle World for this story by that good and trusting soul-your troubles are just beginning. For now you relearn how to operate motorcycle controls. The Indian’s clutch is a rocker pedal operated by your left foot. Rock that forward-it holds itself disengaged until you decide otherwise. Bring engine idle to its lowest point, move the shift lever back in its neutral gate toward second, then snap it carefully but firmly forward into first. Now, applying progressively more throttle, engage the clutch and move out. It sounds easy. It isn’t. Because the leftfoot, left-wrist action is so foreign, the staffers who rode this bike all killed it at least once while attempting their first launch. It really takes some getting used to.

Once you’re used to it, however, you’re well on your way toward being captivated by the big Chief’s charms. Under way, shifting becomes natural, even though too hard a pull on the lever will bring the transmission all the way through second and into third gear. You soon learn to feel second, positioning the thumb of your shifting hand just so over the tank’s oil-reservoir cap.

Out on the road, the Triumph is light and nimble, but vibrates so hard that your hands soon itch and go numb. Not even the chassis’ weird motion—it bobs up and down on its fork, with the rear axle as the pivot-point of this motion-will take your mind off this. Also, this example exhibited a bit of fragility that required sympathetic handling: On a long uphill climb, it temporarily seized while under the control of the Editor-in-Chief, while the Indian, with which it was being ridden, motored robustly along. Happy, robust motoring might just be the Indian’s catch-phrase. It’s a big, funky bike, with its own special brand of mellowness aided greatly by that huge sprung saddle. Get it in top gear and it just pulls, at any speed, and rides in surprising comfort. Compared to the Triumph, its engine is very smooth, so much so that at idle, in traffic, you can’t be sure that it is even running.

Out on the road, both these bikes perform like the senior citizens they are. They accelerate, but not briskly. If one uses both brakes, they stop, eventually. Neither suffers bumps gladly. They’re period pieces, after all, and while the Indian does pull smartly away from the Triumph in roll-on tests, the Triumph, with its easier to use hand clutch and foot shift, confuses the issue by getting through the quartermile a bit faster and more quickly—17.14 seconds at 76.14 mph, compared to the Indian’s 18.88 seconds at 72.17 mph.

In 1947, that was terrific performance. Today, those times show us how far motorcycles have come-which is very far indeed. You only have to look at the spiritual descendants of these motorcycles to see how far. The Speed Twin’s closest living relative? Certainly not the new Triumphs. The bike most closely linked to this old Speed Twin might be something like Kawasaki’s nimble, vertical-Twin-powered Ninja 500. The Indian’s surviving next-of-kin? Any HarleyDavidson Big Twin, with that whole family possessed of the same basic look and heartbeat.

Heartbeat is precisely what these bikes are about. They recall the slower, more even tempo of milder, less crazy times-times when Indian was content with status quo and Triumph was willing to take a step forward. Those times shaped the bikes into what they were then, and into what they are now. Then, they were competitors, state-of-the-art equipment meant to put enthusiasts on the road. Today, they’re looking glasses that remind us how things used to be, industrial icons that provide anchors of traditionalism in a world blown by the winds of change. That's why each is desirable enough to be very valuable. And that’s why each is, in its own way, immensely satisfying to ride.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontRamblings

March 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsMotorcycling For the Duration

March 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCNo Sharp Corners

March 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1995 -

Roundup

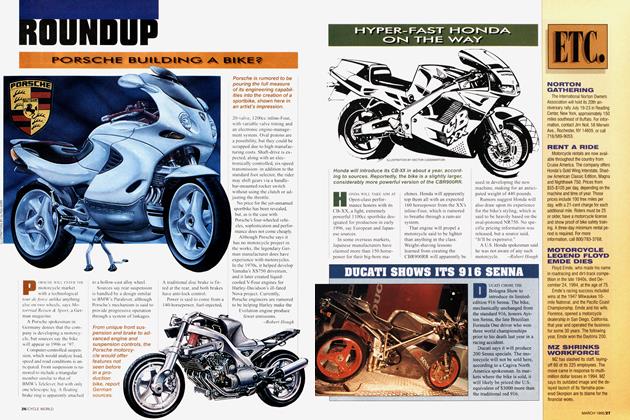

RoundupPorsche Building A Bike?

March 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupHyper-Fast Honda On the Way

March 1995 By Robert Hough