THE VINTAGE EXPERIENCE

EEK! HERE COMES TURN ONE

JON F. THOMPSON

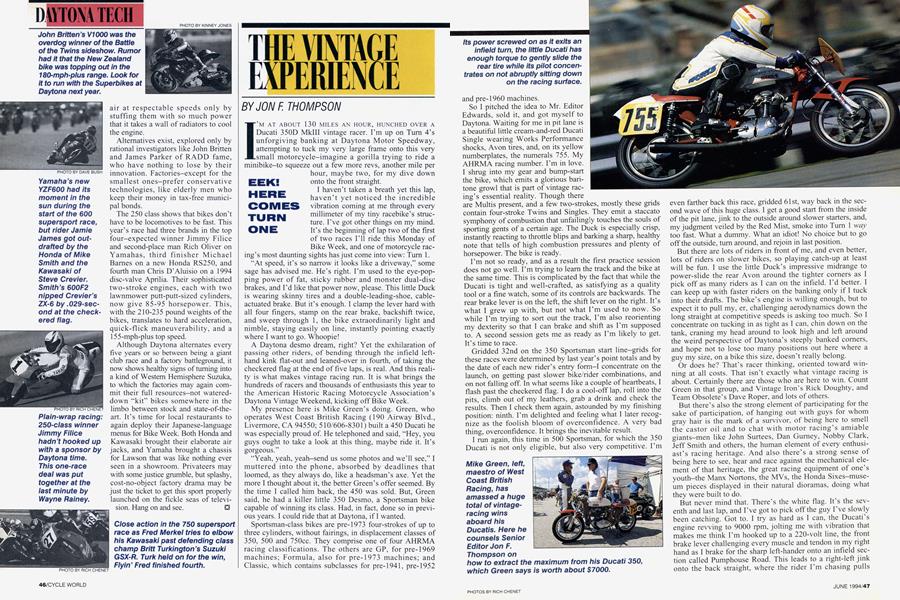

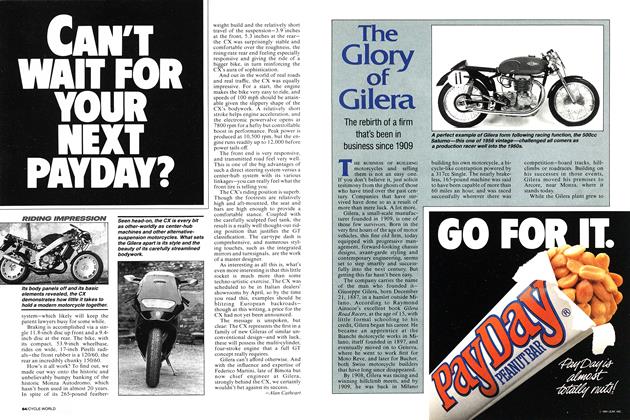

I'M AT ABOUT 130 MILES AN HOUR, HUNCHED OVER A Ducati 350D MkIII vintage racer. I'm up on Turn 4's unforgiving banking at Daytona Motor Speedway, attempting to tuck my very large frame onto this very small motorcycle—imagine a gorilla trying to ride a minibike—to squeeze out a few more revs, another mile per

hour, maybe two, for my dive down onto the front straight.

I haven’t taken a breath yet this lap, haven’t yet noticed the incredible vibration coming at me through every millimeter of my tiny racebike’s structure. I’ve got other things on my mind. It’s the beginning of lap two of the first of two races I’ll ride this Monday of Bike Week, and one of motorcycle rac-

ing’s most daunting sights has just come into view: Tum 1.

“At speed, it’s so narrow it looks like a driveway,” some sage has advised me. He’s right. I’m used to the eye-popping power of fat, sticky rubber and monster dual-disc brakes, and I’d like that power now, please. This little Duck is wearing skinny tires and a double-leading-shoe, cableactuated brake. But it’s enough. I clamp the lever hard with all four fingers, stamp on the rear brake, backshift twice, and sweep through 1, the bike extraordinarily light and nimble, staying easily on line, instantly pointing exactly where I want to go. Whoopie!

A Daytona desmo dream, right? Yet the exhilaration of passing other riders, of bending through the infield lefthand kink flat-out and leaned-over in fourth, of taking the checkered flag at the end of five laps, is real. And this reality is what makes vintage racing run. It is what brings the hundreds of racers and thousands of enthusiasts this year to the American Historic Racing Motorcycle Association’s Daytona Vintage Weekend, kicking off Bike Week.

My presence here is Mike Green’s doing. Green, who operates West Coast British Racing (190 Airway Blvd., Livermore, CA 94550; 510/606-8301) built a 450 Ducati he was especially proud of. He telephoned and said, “Hey, you guys ought to take a look at this thing, maybe ride it. It’s gorgeous.”

“Yeah, yeah, yeah-send us some photos and we’ll see,” I muttered into the phone, absorbed by deadlines that loomed, as they always do, like a headsman’s axe. Yet the more I thought about it, the better Green’s offer seemed. By the time I called him back, the 450 was sold. But, Green said, he had a killer little 350 Desmo, a Sportsman bike capable of winning its class. Had, in fact, done so in previous years. I could ride that at Daytona, if I wanted.

Sportsman-class bikes are pre-1973 four-strokes of up to three cylinders, without fairings, in displacement classes of 350, 500 and 750cc. They comprise one of four AHRMA racing classifications. The others are GP, for pre-1969 machines; Formula, also for pre-1973 machines; and Classic, which contains subclasses for pre-1941, pre-1952 and pre-1960 machines. So I pitched the idea to Mr. Editor Edwards, sold it, and got myself to Daytona. Waiting for me in pit lane is a beautiful little cream-and-red Ducati Single wearing Works Performance shocks, Avon tires, and, on its yellow numberplates, the numerals 755. My AHRMA racing number. I'm in love. I shrug into my gear and bump-start the bike, which emits a glorious bari tone growl that is part of vintage rac ing's essential reality. Though there

are Multis present, and a few two-strokes, mostly these grids contain four-stroke Twins and Singles. They emit a staccato symphony of combustion that unfailingly touches the souls of sporting gents of a certain age. The Duck is especially crisp, instantly reacting to throttle blips and barking a sharp, healthy note that tells of high combustion pressures and plenty of horsepower. The bike is ready.

I’m not so ready, and as a result the first practice session does not go well. I’m trying to learn the track and the bike at the same time. This is complicated by the fact that while the Ducati is tight and well-crafted, as satisfying as a quality tool or a fine watch, some of its controls are backwards. The rear brake lever is on the left, the shift lever on the right. It's what I grew up with, but not what I’m used to now. So while I’m trying to sort out the track, I’m also reorienting my dexterity so that I can brake and shift as I’m supposed to. A second session gets me as ready as I’m likely to get. It’s time to race.

Gridded 32nd on the 350 Sportsman start line-grids for these races were determined by last year’s point totals and by the date of each new rider’s entry form-I concentrate on the launch, on getting past slower bike/rider combinations, and on not falling off. In what seems like a couple of heartbeats, I flash past the checkered flag. I do a cool-off lap, roll into the pits, climb out of my leathers, grab a drink and check the results. Then I check them again, astounded by my finishing position: ninth. I’m delighted and feeling what I later recognize as the foolish bloom of overconfidence. A very bad thing, overconfidence. It brings the inevitable result.

I run again, this time in 500 Sportsman, for which the 350 Ducati is not only eligible, but also very competitive. I’m even farther back this race, gridded 61st, way back in the second wave of this huge class. I get a good start from the inside of the pit lane, jink to the outside around slower starters, and, my judgment veiled by the Red Mist, smoke into Tum 1 way too fast. What a dummy. What an idiot! No choice but to go off the outside, turn around, and rejoin in last position.

But there are lots of riders in front of me, and even better, lots of riders on slower bikes, so playing catch-up at least will be fun. I use the little Duck’s impressive midrange to power-slide the rear Avon around the tighter corners as I pick off as many riders as I can on the infield. I’d better. I can keep up with faster riders on the banking only if I tuck into their drafts. The bike’s engine is willing enough, but to expect it to pull my, er, challenging aerodynamics down the long straight at competitive speeds is asking too much. So I concentrate on tucking in as tight as I can, chin down on the tank, craning my head around to look high and left around the weird perspective of Daytona’s steeply banked comers, and hope not to lose too many positions out here where a guy my size, on a bike this size, doesn’t really belong.

" Or does he? That’s racer thinking, oriented toward winning at all costs. That isn’t exactly what vintage racing is about. Certainly there are those who are here to win. Count Green in that group, and Vintage Iron’s Rick Doughty, and Team Obsolete’s Dave Roper, and lots of others.

But there’s also the strong element of participating for the sake of participation, of hanging out with guys for whom gray hair is the mark of a survivor, of being here to smell the castor oil and to chat with motor racing’s amiable giants—men like John Surtees, Dan Gumey, Nobby Clark, Jeff Smith and others, the human element of every enthusiast’s racing heritage. And also there’s a strong sense of being here to see, hear and race against the mechanical element of that heritage, the great racing equipment of one’s youth-the Manx Nortons, the MVs, the Honda Sixes-museum pieces displayed in their natural dioramas, doing what they were built to do.

But never mind that. There’s the white flag. It’s the seventh and last lap, and I’ve got to pick off the guy I’ve slowly been catching. Got to. I try as hard as I can, the Ducati s engine revving to 9000 rpm, jolting me with vibration that makes me think I’m hooked up to a 220-volt line, the front brake lever challenging every muscle and tendon in my right hand as I brake for the sharp left-hander onto an infield section called Pumphouse Road. This leads to a right-left jink onto the back straight, where the rider I’m chasing pulls inevitably away from me. I close up again through the Chicane, but can’t quite pass. Out of the Chicane and onto the banking, he's gone. Can't catch him now, and there's the checkered flag. Ah, well.

Back in the WCBR pits, shed of perspiration-soaked leathers and gulping down any liquid I can find, I’m astounded by the results. I finish 22nd overall, fifth in the second wave. Hey, it could have been worse, considering my unorthodox approach to this race’s first turn, and I’m satisfied with the result.

The greater result, though, is a racing experience unlike any other in this day of crowd control, corporate sponsorship and riders who view the world through accountant’s eyes. I may have to get serious, invest in a racebike. It’s possible. Green’s race-ready Ducati 350s start at $4000. You can spend a lot more than that, but you also can buy your own bike and raceprep it yourself for a lot less. I notice an ad in the AHRMA rule book that offers, “All your racing needs, from a bike to proper clothing to a marriage counselor.” Hmm. And then there’s the bumper sticker I see in pit lane. It says, “This marriage is on hold while we bring you the racing season.”

It’s proof, I think, that the vintage racing community fully

understands the implications of what it has wrought.