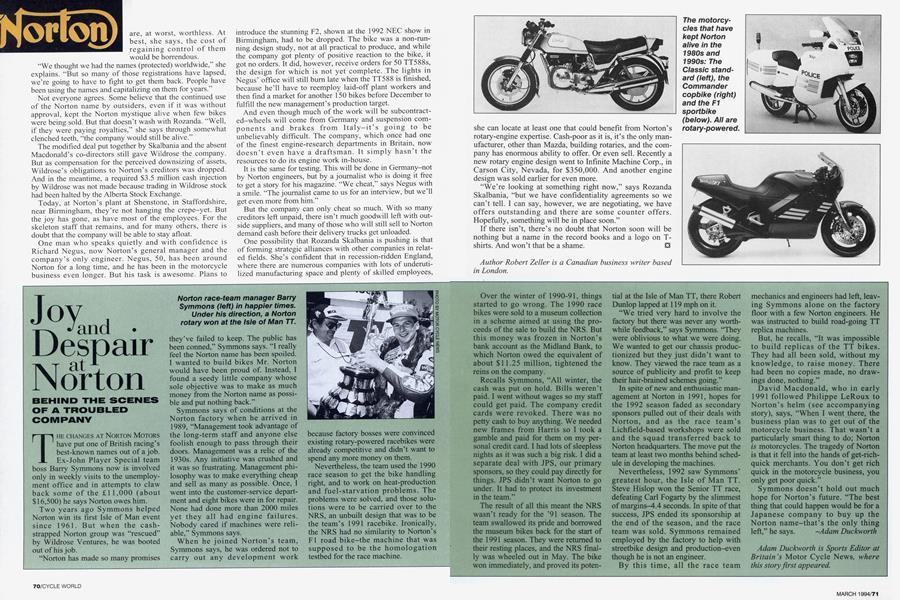

Joy and Despair at Norton

BEHIND THE SCENES OF A TROUBLED COMPANY

THE CHANGES AT NORTON MOTORS have put one of British racing's best-known names out of a job. Ex-John Player Special team boss Barry Symmons now is involved only in weekly visits to the unemployment office and in attempts to claw back some of the £11,000 (about $16,500) he says Norton owes him.

Two years ago Symmons helped Norton win its first Isle of Man event since 1961. But when the cashstrapped Norton group was “rescued” by Wildrose Ventures, he was booted out of his job.

“Norton has made so many promises they’ve failed to keep. The public has been conned,” Symmons says. “I really feel the Norton name has been spoiled. I wanted to build bikes Mr. Norton would have been proud of. Instead, I found a seedy little company whose sole objective was to make as much money from the Norton name as possible and put nothing back.”

Symmons says of conditions at the Norton factory when he arrived in 1989, “Management took advantage of the long-term staff and anyone else foolish enough to pass through their doors. Management was a relic of the 1930s. Any initiative was crushed and it was so frustrating. Management philosophy was to make everything cheap and sell as many as possible. Once, I went into the customer-service department and eight bikes were in for repair. None had done more than 2000 miles yet they all had engine failures. Nobody cared if machines were reliable,” Symmons says.

When he joined Norton’s team, Symmons says, he was ordered not to carry out any development work because factory bosses were convinced existing rotary-powered racebikes were already competitive and didn’t want to spend any more money on them.

Nevertheless, the team used the 1990 race season to get the bike handling right, and to work on heat-production and fuel-starvation problems. The problems were solved, and those solutions were to be carried over to the NRS, an unbuilt design that was to be the team’s 1991 racebike. Ironically, the NRS had no similarity to Norton’s FI road bike-the machine that was supposed to be the homologation testbed for the race machine.

Over the winter of 1990-91, things started to go wrong. The 1990 race bikes were sold to a museum collection in a scheme aimed at using the proceeds of the sale to build the NRS. But this money was frozen in Norton’s bank account as the Midland Bank, to which Norton owed the equivalent of about $11.25 million, tightened the reins on the company.

Recalls Symmons, “All winter, the cash was put on hold. Bills weren’t paid. I went without wages so my staff could get paid. The company credit cards were revoked. There was no petty cash to buy anything. We needed new frames from Harris so I took a gamble and paid for them on my personal credit card. I had lots of sleepless nights as it was such a big risk. I did a separate deal with JPS, our primary sponsors, so they could pay directly for things. JPS didn’t want Norton to go under. It had to protect its investment in the team.”

The result of all this meant the NRS wasn’t ready for the ’91 season. The team swallowed its pride and borrowed the museum bikes back for the start of the 1991 season. They were returned to their resting places, and the NRS finally was wheeled out in May. The bike won immediately, and proved its poten-

tial at the Isle of Man TT, there Robert Dunlop lapped at 119 mph on it.

“We tried very hard to involve the factory but there was never any worthwhile feedback,” says Symmons. “They were oblivious to what we were doing. We wanted to get our chassis productionized but they just didn’t want to know. They viewed the race team as a source of publicity and profit to keep their hair-brained schemes going.”

In spite of new and enthusiastic management at Norton in 1991, hopes for the 1992 season faded as secondary sponsors pulled out of their deals with Norton, and as the race team’s Lichfield-based workshops were sold and the squad transferred back to Norton headquarters. The move put the team at least two months behind schedule in developing the machines.

Nevertheless, 1992 saw Symmons’ greatest hour, the Isle of Man TT. Steve Hislop won the Senior TT race, defeating Carl Fogarty by the slimmest of margins-4.4 seconds. In spite of that success, JPS ended its sponsorship at the end of the season, and the race team was sold. Symmons remained employed by the factory to help with streetbike design and production-even though he is not an engineer.

By this time, all the race team

mechanics and engineers had left, leaving Symmons alone on the factory floor with a few Norton engineers. He was instructed to build road-going TT replica machines.

But, he recalls, “It was impossible to build replicas of the TT bikes. They had all been sold, without my knowledge, to raise money. There had been no copies made, no drawings done, nothing.”

David Macdonald, who in early 1991 followed Philippe LeRoux to Norton’s helm (see accompanying story), says, “When I went there, the business plan was to get out of the motorcycle business. That wasn’t a particularly smart thing to do; Norton is motorcycles. The tragedy of Norton is that it fell into the hands of get-richquick merchants. You don’t get rich quick in the motorcycle business, you only get poor quick.”

Symmons doesn't hold out much hope for Norton's future. "The best thing that could happen would be for a Japanese company to buy up the Norton name-that's the only thing left," he says.

Adam Duckworth

Adam Duckworth is Sports Editor at Britain `s Motor Cycle News, where this story first appeared.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue