RACING TO THE CLOUDS

RACE WATCH

Pikes Peak: For the lucky and the brave

JON F. THOMPSON

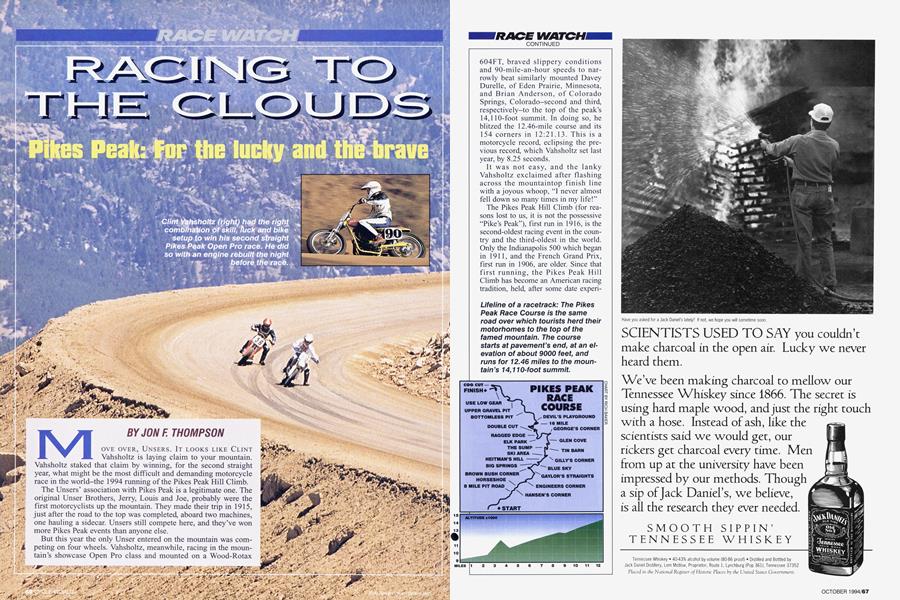

MOVE OVER, UNSERS. IT LOOKS LIKE CLINT Vahsholtz is laying claim to your mountain. Vahsholtz staked that claim by winning, for the second straight year, what might be the most difficult and demanding motorcycle race in the world-the 1994 running of the Pikes Peak Hill Climb.

The Unsers’ association with Pikes Peak is a legitimate one. The original Unser Brothers, Jerry, Louis and Joe, probably were the first motorcyclists up the mountain. They made their trip in 1915, just after the road to the top was completed, aboard two machines, one hauling a sidecar. Unsers still compete here, and they’ve won more Pikes Peak events than anyone else.

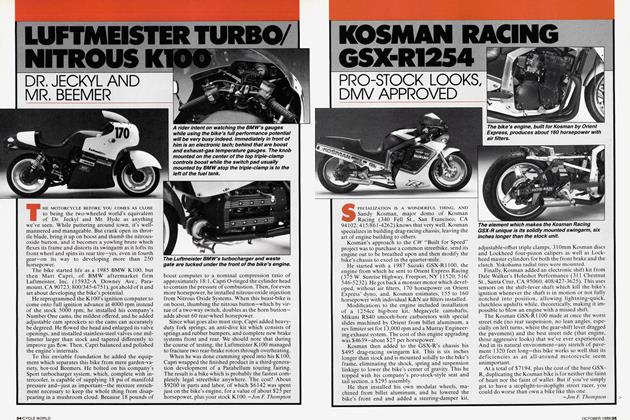

But this year the only Unser entered on the mountain was competing on four wheels. Vahsholtz, meanwhile, racing in the mountain’s showcase Open Pro class and mounted on a Wood-Rotax 604FT, braved slippery conditions and 90-mile-an-hour speeds to narrowly beat similarly mounted Davey Durelle, of Eden Prairie, Minnesota, and Brian Anderson, of Colorado Springs, Colorado-second and third, respectively-to the top of the peak’s 14,110-foot summit. In doing so, he blitzed the 12.46-mile course and its 154 corners in 12:21.13. This is a motorcycle record, eclipsing the previous record, which Vahsholtz set last year, by 8.25 seconds.

It was not easy, and the lanky Vahsholtz exclaimed after flashing across the mountaintop finish line with a joyous whoop, “I never almost fell down so many times in my life!”

The Pikes Peak Hill Climb (for reasons lost to us, it is not the possessive “Pike’s Peak”), first run in 1916, is the second-oldest racing event in the country and the third-oldest in the world. Only the Indianapolis 500 which began in 1911, and the French Grand Prix, first run in 1906, are older. Since that first running, the Pikes Peak Hill Climb has become an American racing tradition, held, after some date experimentation, every July 4th. It sorely lacks the organizational professionalism that accompanies other racing events, but that’s a function of the race’s amateur status, and of the fact that it pays no prize money, and no points in any racing championship. Pikes Peak is just west of Colorado Springs. Though becoming generally known in the mid-19th century through the “Pikes Peak or Bust” rallying cry of miners bound for the nearby Cripple Creek goldfields, it was “discovered” in 1806 by Zebulon M. Pike, a soldier and explorer killed in the War of 1812. Pike, a young Army officer, found himself in the uncharted and unmapped West in 1805-06 as a result of orders to explore the sources of the Mississippi River and to purchase fort sites from the indigenous peoples. Lost and short on supplies, Pike tried to climb the mountain. He failed, and pronounced it unclimbable.

At least three generations of racers have proven him wrong. They’ve done so on a difficult and winding mountain road that was opened in 1915. It’s a changeable, moody bitch of a road that every July 4th becomes the Dark Queen of American racing, both in color and in temperament. The road traces its dull line over the mountain’s pink granite thanks to a coating of liquid magnesium chloride. This darkens the gravel, brings the surface to an almost-asphalt hardness and virtually eliminates dust. It also makes it incredibly inconsistent. In spite of the treatment, the road is still dirt, and the torture inflicted on it over race weekend forms chuckholes and stutter bumps. If a racer strays off line at all, he finds himself in marbles that can put him off the road. Make a mistake, the mountain will throw you down and step on you. Go off one of the road’s cliff-edged “blue-sky corners,” so named because that’s all there is outside them, and you’ll need a parachute. You’ll have a birthday before you hit ground. Tourists, gasping slowly up the mountain in overloaded and overheated sedans, fall off the road. Even the road’s superintendent has driven off. And one driver not long ago used the road and its spectacular drops as the weapon for his suicide. Yet in the race itself, there’s been just one fatality, unfortunately a motorcyclist. That came in the early 1980s, when the race was run on untreated gravel, and when all motorcyclists were started at the same time. According to Bill Brokaw, the race’s motorcycle referee, “The guy fell in the dust and got hit by another rider. That scared everybody pretty bad.” So bad, in fact that for a while motorcycles, which have participated inconsistently at best, again were excluded from the event.

This year was the fourth year back on the mountain for bikes, and the event was trouble-free, with the most serious injuries among the 70 motorcycle racers in four classes-Open and 250 Pro, Open and 250 Amateurbeing a broken collarbone and a dislocated shoulder. That doesn’t mean that the road’s ever-changing surface made things easy. The problems for racers remain four-fold: 1) How to jet for a course that starts at a forested 9000 feet of elevation and ends at a rocksand-ice 14,110 feet; 2) how to jet when practice and qualifying are held in the cool, dense air of early morning while the race is held in the warmer, less-dense air of mid-day; 3) what tires to use; and 4) how to imbed the road’s endless variety of corners-with names like Horseshoe, Picnic Ground, Brown Bush, Gravel Pit and Use Low Gear-into your memory.

Experienced racers here show up with bewildering numbers and varieties of main jets, pilot jets, needles and slides, and they experiment constantly. If you don’t know your racebike’s carburetor when you arrive here, you will by the time you leave. Or maybe you’ll just go nuts. For how is it possible, over this altitude range, to provide the crisp throttle response needed for the course’s tight lower half, and also for the sheer horsepower required on the more open upper half?

Brian Anderson, with three Open Pro wins in his pocket, knows as well as anyone how to do it. He said, “I jet it as lean as possible, just so it won’t seize at the bottom.” Davey Durelle, who three times has finished second here, says, “I jet for about 11,000 feet and let it starve at the bottom and run a little rich on the top.”

It isn’t easy to get right. Miss it, and you lose even before you start. Confirms Brokaw, “There’s just no room to be sloppy with your jetting.” Tire choice and chassis setup are equally problematic, especially for those not running flat-track bikes like the Wood-Rotax. Most of those riders, conscious of the mix of flat-track and roadrace riding styles required, install front brakes and opt for dirttrack tires, harder springs and more rebound damping than they’d normally use. What’s the right setup? Says Durelle, “I don’t know. I haven’t found it yet.”

The many riders on motocross and enduro bikes have even more setup trouble than do those riders on flattrack equipment. The most successful ones lower their bikes by as much as 4 inches into DTX form, and some are using pavement-oriented dual-purpose tires. Larry Kleinschmidt, here on a purpose-bought Yamaha WR250 from Laguna Niguel, California, is one of these. He qualifies sixth 250 Amateur, finishes a disputed fourth after initially being credited with a much faster run. He says of his tire choice, “The tires worked fabulous. I’d sure like to do it over. I know I can do better.”

Doing it over is indeed the key. The most successful riders are the ones that have done this road many, many times. Scott Dunlavey, here from Lafayette, California, to race in Open Amateur, calls it, “A 154-corner TT track you’ve never seen before.” Getting it figured out is complicated by limited race-week practice sessions and by the fact that the entire course isn’t open to practice. You practice on the top on one day, and on the bottom the next. You do it early, arriving in the pits-a road-side campground-at 4:30 a.m. For until raceday, the road opens to civilian traffic at 10 a.m.

Experience is vital, and local riders like Anderson and Vahsholtz clearly have an advantage. Says Durelle, “All those hairpins and switchbacks-there are lots of blind corners that can be deceiving.”

Says Arlo Englund, of Colorado Springs, “You gotta know the road, and you gotta know how to keep your momentum up. You’ve got to learn the road perfect.”

There is at least one videotape of the road available, made by a racer with a lipstick video camera strapped to his helmet. But of this, Englund says, “That can be misleading. You’ve got to know where you are (on the course) and the tape can disorient you.”

Oh, and there is one other thing you need, says Englund, who this year DNFed: “If you don’t have confidence, you’re either totally crazy or you’re out of luck.”

This year, those with the greatest combination of confidence, luck, preparation and experience are the five riders on the front row of Open Pro: Vahsholtz on pole; Paul Zinke, like Vahsholtz, of Woodland Park, Colorado; Durelle, Englund and Anderson. Such is the quality of this front row that Anderson says afterward, “This is what makes this fun. You can trust everybody. You’re on the gas, there’s no bump-and-shove, it’s all a clean deal.”

The bikes run this year during a break in the car/truck competition. The four-wheeler event, with its 57 entrants, grinds on all day, with racers up the mountain at two-minute intervals. But the bike event is over, seemingly, as soon as it starts, all 80 bikes flagged off in furious groups of five at one-minute intervals. The Open Pro race is the event of the day, with action all the way from start to finish. Vahsholtz, Durelle and Englund get great starts, and the first four squeeze Zinke out, leaving Anderson running between Zinke and the front three.

“I caught up to everybody at the Ski Area (a corner on the course’s lower section),” said Anderson, “and I went for the Big Pass. I locked up the front wheel and just about went off the road.”

Zinke, too, had his moment: “I caught up to Brian toward the top, but just before The Ws I ran a little too hard and got way wide. I stayed on the gas, but there was no way I could catch Brian.”

Englund by now had fallen out with engine trouble, and the race for the lead was between Durelle, thoroughly disgusted with his two previous second-places, and Vahsholtz, who during practice and qualifying rode brilliantly and aggressively. Said Vahsholtz, “Davey passed me in the Bottomless > Pit, I went back by and almost fell, and he went back by. At 19 Mile I caught back up and he looked back. When he did that I think he lost his concentration.”

Whatever happened, braking into the next-to-last hairpin, a blue-sky turn called Cog Cut, Durelle went in too hot. He braked too hard and killed his bike’s engine.

“When I came up on him he was trying to bump-start it,” said Anderson. “He had such a big lead he still beat me to the finish line. Durelle should have won it. He had it won. He killed us,” Anderson added.

“Davey had me beat,” confirmed Vahsholtz, “he just tried to charge it like we did in practice, and the road wouldn’t give him that.”

Said Durelle, “Every comer is so different, you never know what to expect. Riding on the edge gets a little weird, you’re trying so hard. There is room for error, but not a lot. I hate being second. I’ll be back. I’ve got to win.”

Not every racer here has Durelle’s super-competitive nature. Said Kleinschmidt, “It doesn’t matter if you do good or not. It’s the most fun of any kind of racing I’ve done. I don’t know if it’s the fact that it’s a combination of all kinds of riding skills, or what, but it’s an absolute blast.”

Sidney Dickson, a 57-year-old treemover from St. Michaels, Maryland, said, “This is beyond fun. It’s a spiritual experience. There’s no place like it. Everybody who gets to the top is secretly relieved. It’s the kind of thing you stick a feather in your cap for.”

Indeed, so great is the allure of the Pikes Peak Hill Climb that the vast majority of participants are repeaters. In fact, it’s possible that the Pikes Peak Hill Climb is a much better deal for participants than it is for observers. Observe, and you see the racers one time, in one corner, and then you’re faced with a dismal, bumperto-bumper, three-hour trip off the mountain. But become one of the few racers that organizers accept, and you see the road to the top of Pikes Peak, all 154 corners, from atop a racebike. And you’ll experience one of American’s most beloved racing traditions. It’s a tradition that calls racers back for repeat performances. It’s a tradition that carves the names of the lucky and the brave into the Pikes Peak record book.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Last Indian

October 1994 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsZx-11: the Bike Can't Help It

October 1994 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCGrace In Hardware

October 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1994 -

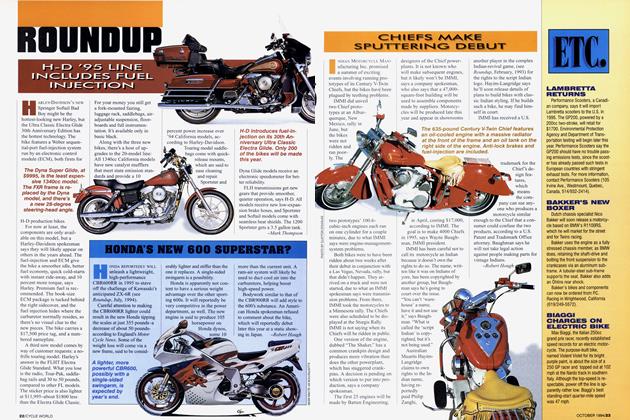

Roundup

RoundupH-D `95 Line Includes Fuel Injection

October 1994 By Mark Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's New 600 Superstar?

October 1994 By Robert Hough