MUSTANG

The 20-year history of an almost-motorcycle

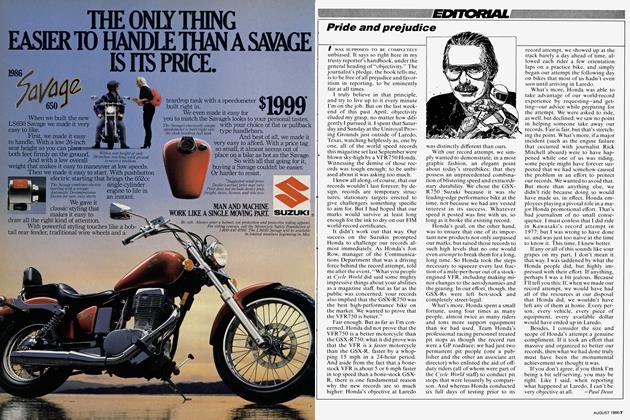

SAY THE WORD "MUSTANG" TO MOST PEOPLE TOday, and they'll probably think you're talking about a 1960s ponycar. But long before Ford Motor Company's runaway sales success was even a gleam in Lee lacocca's eye, another Mustang had been a reality. This one was the two-wheeled brain-child of engineer John Gladden, whose Glendale, California, company manufactured aircraft parts during World War II.

When the war came to an end and Gladden had to figure out what to do with his now-quiet plant, his thoughts turned to his favorite pre-war activity: motorcycles. What was needed, Gladden decided, was an inexpensive, lightweight bike that could serve as a transition between a motorscooter and a full-sized motorcycle.

Gladden laid out the plans for the first Mustang with the assistance of engineer and fellow motorcycle enthusiast Howard Forrest, who was participating in the design of a new air-cooled, single-cylinder industrial engine to be built by Gladden. The bike, scheduled for sale in 1945, was to be powered by a I25cc Villers two-stroke Single. A few of these machines, called the Colt, were produced, but the limited availability of the British-built Villiers engines prompted a redesign of the Colt to accept Gladden’s own engine.

The result was the Model 2, which became available in the fall of 1947. It featured a single-cylinder, 320cc side-valve engine, a three-speed Burman transmission, a tubular front fork, a solid rear suspension,

disc wheels and 4.00x12 tires. The bike had a wheelbase of 50 inches, a seat height of 27.5 inches and a dry weight of 215 pounds. It was followed in 1950 by the updated Model 4, also known as the Standard.

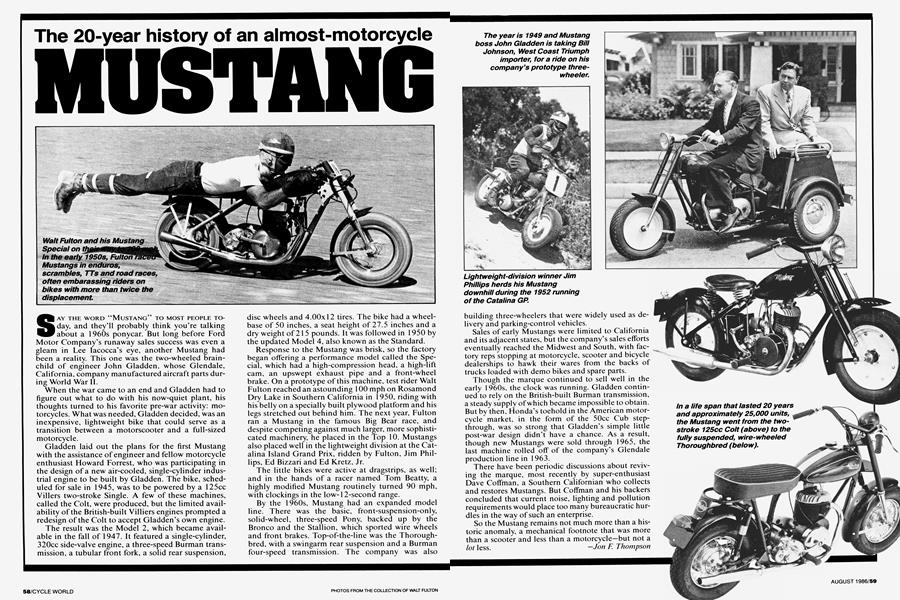

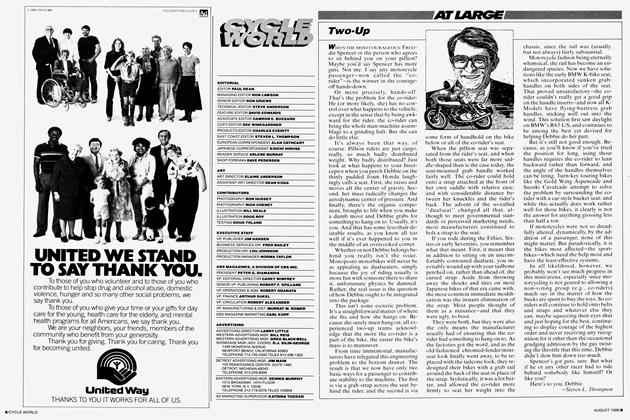

Response to the Mustang was brisk, so the factory began offering a performance model called the Special, which had a high-compression head, a high-lift cam, an upswept exhaust pipe and a front-wheel brake. On a prototype of this machine, test rider Walt Fulton reached an astounding 100 mph on Rosamond Dry Lake in Southern California in 1950, riding with his belly on a specially built plywood platform and his legs stretched out behind him. The next year, Fulton ran a Mustang in the famous Big Bear race, and despite competing against much larger, more sophisticated machinery, he placed in the Top 10. Mustangs also placed well in the lightweight division at the Catalina Island Grand Prix, ridden by Fulton, Jim Phillips, Ed Bizzari and Ed Kretz, Jr.

The little bikes were active at dragstrips, as well; and in the hands of a racer named Tom Beatty, a highly modified Mustang routinely turned 90 mph, with clockings in the low-12-second range.

By the 1960s, Mustang had an expanded model line. There was the basic, front-suspension-only, solid-wheel, three-speed Pony, backed up by the Bronco and the Stallion, which sported wire wheels and front brakes. Top-of-the-line was the Thoroughbred, with a swingarm rear suspension and a Burman four-speed transmission. The company was also

building three-wheelers that were widely used as delivery and parking-control vehicles.

Sales of early Mustangs were limited to California and its adjacent states, but the company’s sales efforts eventually reached the Midwest and South, with factory reps stopping at motorcycle, scooter and bicycle dealerships to hawk their wares from the backs of trucks loaded with demo bikes and spare parts.

Though the marque continued to sell well in the early l 960s, the clock was running. Gladden continued to rely on the British-built Burman transmission, a steady supply of which became impossible to obtain. But by then, Honda’s toehold in the American motorcycle market, in the form of the 50cc Cub stepthrough, was so strong that Gladden’s simple little post-war design didn’t have a chance. As a result, though new Mustangs were sold through 1965, the last machine rolled off of the company’s Glendale production line in 1963.

There have been periodic discussions about reviving the marque, most recently by super-enthusiast Dave Coffman, a Southern Californian who collects and restores Mustangs. But Coffman and his backers concluded that current noise, lighting and pollution requirements would place too many bureaucratic hurdles in the way of such an enterprise.

So the Mustang remains not much more than a historic anomaly, a mechanical footnote that was more than a scooter and less than a motorcycle-but not a lot less. Jon F. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue