DIRT DINOSAURS

MOTORCROSS MAESTROS WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE

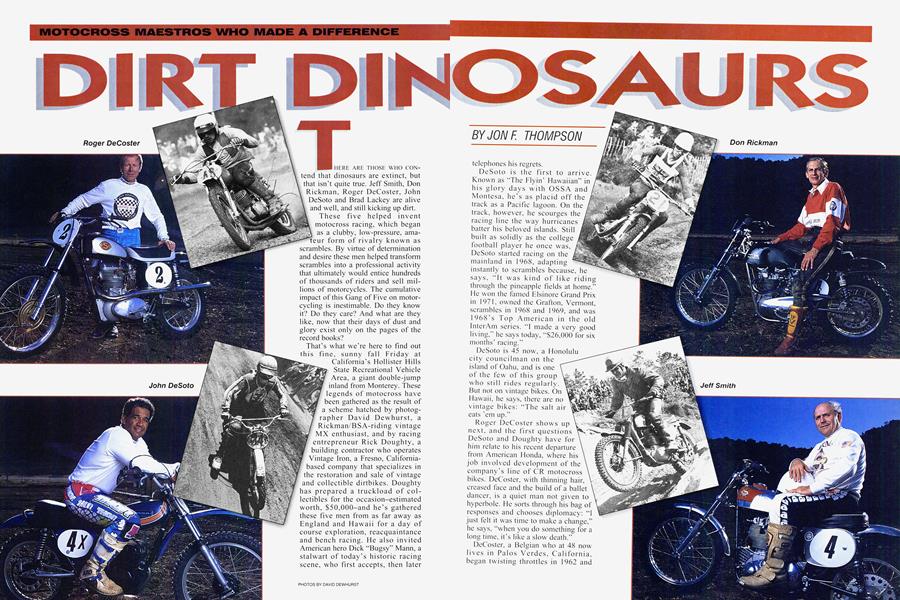

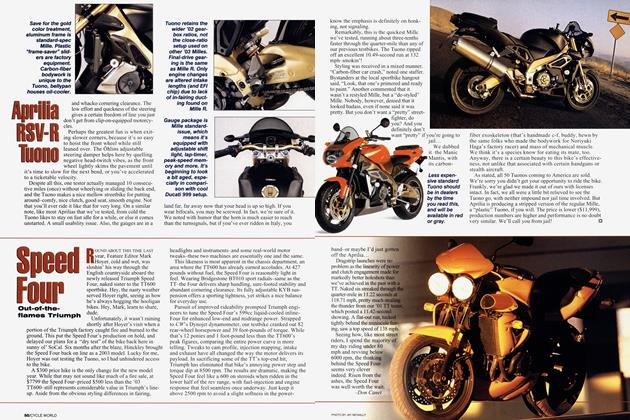

THERE ARE THOSE WHO CONtend that dinosaurs are extinct, but that isn't quite true. Jeff Smith, Don Rickman, Roger DeCoster, John DeSoto and Brad Lackey are alive and well, and still kicking up dirt. These five helped invent motocross racing, which began as a clubby, low-pressure, amateur form of rivalry known as scrambles. By virtue of determination and desire these men helped transform scrambles into a professional activity that ultimately would entice hundreds of thousands of riders and sell millions of motorcycles. The cumulative impact of this Gang of Five on motorcycling is inestimable. Do they know it? Do they care? And what are they like, now that their days of dust and glory exist only on the pages of the record books?

That’s what we’re here to find out this fine, sunny fall Friday at California’s Hollister Hills State Recreational Vehicle Area, a giant double-jump inland from Monterey. These legends of motocross have been gathered as the result of a scheme hatched by photographer David Dewhurst, a Rickman/BSA-riding vintage MX enthusiast, and by racing entrepreneur Rick Doughty, a building contractor who operates Vintage Iron, a Fresno, Californiabased company that specializes in the restoration and sale of vintage and collectible dirtbikes. Doughty has prepared a truckload of collectibles for the occasion-estimated worth, $50,000-and he’s gathered these five men from as far away as England and Hawaii for a day of course exploration, reacquaintance and bench racing. He also invited American hero Dick “Bugsy” Mann, a stalwart of today’s historic racing scene, who first accepts, then later telephones his regrets.

JON F. THOMPSON

DeSoto is the first to arrive. Known as “The Flyin' Hawaiian” in his glory days with OSSA and Montesa, he’s as placid off the track as a Pacific lagoon. On the track, however, he scourges the racing line the way hurricanes batter his beloved islands. Still built as solidly as the college football player he once was, DeSoto started racing on the mainland in 1968, adapting instantly to scrambles because, he says, “It was kind of like riding through the pineapple fields at home.” He won the famed Elsinore Grand Prix in 1971, owned the Grafton, Vermont, scrambles in 1968 and 1969, and was 1 968’s Top American in the old InterAm series. “I made a very good living,” he says today, “$26,000 for six months’ racing.”

DeSoto is 45 now, a Honolulu city councilman on the island of Oahu, and is one of the few of this group who still rides regularly. But not on vintage bikes. On Hawaii, he says, there are no vintage bikes: “The salt air eats ’em up.”

Roger DeCoster shows up next, and the first questions DeSoto and Doughty have for him relate to his recent departure from American Honda, where his job involved development of the company’s line of CR motocross bikes. DeCoster, with thinning hair, creased face and the build of a ballet dancer, is a quiet man not given to hyperbole. He sorts through his bag of responses and chooses diplomacy: “I just felt it was time to make a change,” he says, “when you do something for a long time, it’s like a slow death.”

DeCoster, a Belgian who at 48 now lives in Palos Verdes, California, began twisting throttles in 1962 and raced through 1980. Along the way, he was 500cc motocross world champion an astounding five times, won the 250cc Trophée des Nations 10 times in a row, and the 500cc Motocross des Nations another six times. He goldmedaled in the ’69 ISDT, and was his homeland’s national trials champ that same year. His attitude toward the old bikes here today is one of suspicion. He knows first-hand how competent modern MX bikes are. “The brakes work and they don't vibrate,” he shrugs, adding, “I like to look at the old bikes, but I’m not like Jeff Smith. He thinks they should be ridden.’’

Smith, a British expatriate who makes his home in Wausau, Wisconsin, does indeed think that, but he doesn’t look like any motocrosser you've ever seen. He’s 58 now, and has acquired some of the bulk that often accompanies passage through middle age. But a look into the eyes that twinkle below the gray hair tells the truth about the man. He’s a racer, the same man whose exploits aboard a succession of Gold Stars, B44s and B50s put BSA on the map as a producer of fast, reliable scramblers. Of his first race, in 1951, he says, “There were three people in the race, and I finished third.” Smith was somewhat more successful after that: He was British observed trials champion in 1953 and ’54, British motocross champ nine times and world 500cc MX champ twice. Smith won the Scottish Six Days Trials in 1955 and also took home eight gold medals in ISDT competition. Today, he is executive director of the American Historic Racing Motorcycle Association and rides in AHRMA’s 50-Plus class because, he says, “Dick Mann and I can get together and pretend we’re still young.”

Beating the factory bikes was the motivation that drove Don Rickman and his brother, Derek, to become pioneers. Don, 56, of New Milton, England, still thin and angular, was a very successful scrambles rider in England in the 1950s aboard streetbikes converted to off-road use. In 1958, the Rickmans had a better idea. They invented the specialized dirt racebike, building their own frames to house Triumph engines. The result was the Rickman Metisse. It was, says Rickman, “a bit of a mongrel. The name occurred to us when we happened to look in a French dictionary and found that the word for mongrel was Metisse.” The brothers built a couple for themselves, and the rush was on: “So many people wanted copies, we built a batch of 12,” Rickman remembers, “and we found ourselves in the motorcycle business, where we stayed until the Japanese came in.”

Rickman raced from 1952 to 1970, winning the Motocross des Nations in 1967 and 1968. And then in 1970 he quit, except for occasional exhibition appearances. “I got too old and more sensible,” he says. These days, he still builds Metisse vehicles. These are cars-Ford Sierras with fiberglass bodies in place of their factory-supplied sheetmetal.

Brad Lackey is, at 39, the baby of this bunch. He arrives late, shirtless, fit, tattooed and long-haired, clutching a half-empty beer can, and he yells, “Hey, Pineapple Head,” at DeSoto as he brings his tiny car to a halt. Lackey, of Pleasant Hill, in northern California, was the prototype of a subsequent generation of brash, bad-boy motocrossers. He began riding as a child and was U.S. 500cc national champion in 1972 and 5()0cc world champion in 1982. Now he buys and sells used cars, exporting a few to Europe. And he rides around on his Harley streetbike. He’s stayed retired from the motocross wars these 10 years, he says, simply because “1 don't feel like racing. 1 have no desire to get out there and do the job.”

But Don Rickman does. His physician, having recently completed back surgery on Rickman, warned him not to ride again. “I've been playing squash,” Rickman says, “and that’s strengthened my back.” He has soon changed into his 20-

year-old British-racing-green MX leathers. He’s ready to ride, and drumming up enthusiasm from reluctant co-conspirators who are quite comfortable sitting around in a circle of folding lawn chairs in the shade of Doughty’s motorhome. Soon all are circulating the racetrack, tentatively at first, feeling their way about the 1.1-mile circuit. They begin turning up the heat, and soon something magic has happened: It's as if they’ve never left the racetrack. All of them, that is, but Lackey, whose right hand seems to fit around a beer can better than it fits a throttle grip. Asked if he's going to ride, he just grins, and says enigmatically, “Naw, I think I’ll pass. I can still dance."

So can the others. Their dance partners on this day are a pair of BSA Gold Star Catalina scramblers, one of which Smith sets his sights upon; a pair of Rickmans in 500 and 650cc flavors, the 500cc version for Don Rickman; a beautifully restored 500cc ESO, a 1958 model worth an estimated $12,000, intended for DeCoster; and for DeSoto, his choice of an OSSA or a Montesa.

What’s immediately clear is that once some skills are learned, they stay learned. The first rider to begin feeling comfortable is DeSoto. He’s got the two-stroke OSSA 250 screaming, airborne and crossed-up as he attacks the course, riding with the finesse of an ax murderer. He’s on the gas or on the brakes, sliding, roosting and flying, as spectacular now as he was during his racing career.

“I remember these,” a delighted DeSoto says of the bike, “you’re sideways all the time. You just grab the throttle and hope the back end doesn’t pass the front.”

To varying degrees, the others are less spectacular, but all are deceptively quick. DeCoster, aboard the Czechoslovakianbuilt ESO, finds its front end light, but still flys around the track in spite of never previously having ridden an ESO. Smith and Rickman are the lucky ones. They have no adapting to do, and after a bit, find themselves comfortable aboard their mounts. Because of his explosion of energy, DeSoto looks fast, but he doesn’t stay that way. The OSSA breaks, and then so does the Montesa. Soon DeCoster skids to a halt, the gorgeous ESO silent and seized. Dollar signs loom and Doughty’s face clouds over; spare parts for this bike do not exist in the U.S., and they may not exist in Europe, either. Smith says later of the bike, notorious for its lack of frontend weight, “Eve never ridden one, I just used to watch them go through the fences.”

Soon, DeCoster and DeSoto are back out on the 650 Métissé and the spare Gold Star joining Rickman and Smith for an impromptu moto. Rickman, his style effortless and upright, is, with his feet-up power-slides, clearly able to ride with the other men. Smith looks slow, choosing lines very different from those ridden by anyone else, but we soon see how deceptive his style is. He is incredibly smooth, and that smoothness is easy to mistake for a lack of speed. It isn’t. Smith is hauling ass, so involved that he peels off, does a few practice starts at the MX start gate, and then rejoins the other three as they strafe and attack this unsuspecting piece of northern California real estate. After a while, they slow down, cool off and return to the day’s makeshift pits, their loaner racebikes ready for more and their eyes gleaming, but their bodies tired.

“I’m just not fit enough,” laments Rickman, “you need to be fit to ride one of these.” Walking gingerly, DeSoto says of the 650 Rickman, “These were men’s motorcycles. I don’t know how you guys ever had kids.”

Smith says of his return to a racing Gold Star, “I ought to say it’s frightening, but what I really want to say is that it’s reassuring. It just felt the same as always, the geometry, the weight of the engine. I felt at home the minute I got on this one. This one’s carb works better than I remember....” He bends over the bike, expecting perhaps to find an Amal, looks, and says, “Ah, it’s a Mikuni.”

DeSoto points to the broken Montesa, thinks for a moment,

and says, “Those are the models that...” “...used to hurt you,” chimes in DeCoster, reading DeSoto’s mind. Everyone laughs, and DeSoto, now more serious, comments, “Yeah, a lot of broken bones went into today’s motorcycles.”

As the bench racing played on, the sun began going down, and one by one, the riders changed out of their riding gear, their day of reliving the past as completely used up as the fuel that had been in their racebikes’ gas tanks.

Discussing this group’s impact on the sport, Smith had said, only half-joking, “Whatever we did is held against us, and whatever we do now nobody cares about.” But Smith is wrong. Enthusiasts look at these men and know they’re seeing nothing less than the founders of motocross. Says Doughty, “These guys reflect the beginning of motocross testing, development and evaluation. They’re the essence of professionalism, innovation and true grit.”

Most pioneers are tough to learn about, at least as far as first-hand knowledge is concerned. Lewis & Clark aren’t available. Daniel Boone, Edmund Hillary, Henry Ford and Soichiro Honda also are not granting interviews. But here these guys are, modem pioneers, the men who helped make motocross happen. &

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontGreen Machines

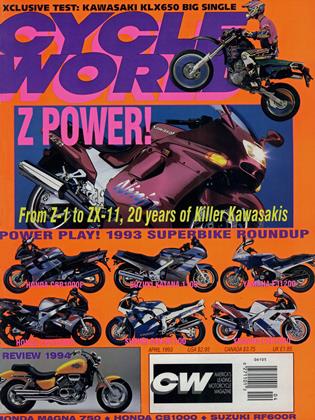

April 1993 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsYou Ain't Goin' Nowhere

April 1993 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCSpring To Action

April 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha To Go Standard?

April 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupBimota Presses On With Gp Streetbike

April 1993 By Alan Cathcart