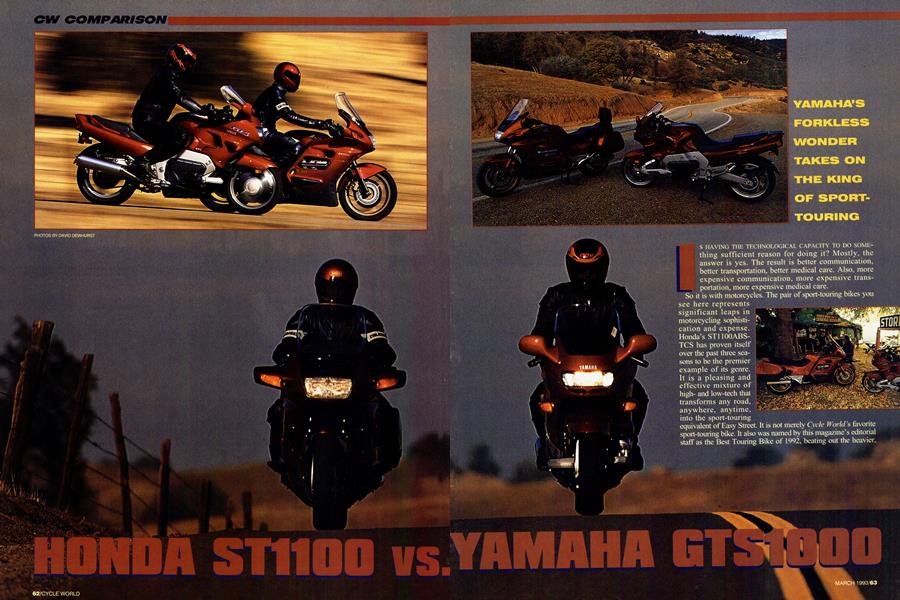

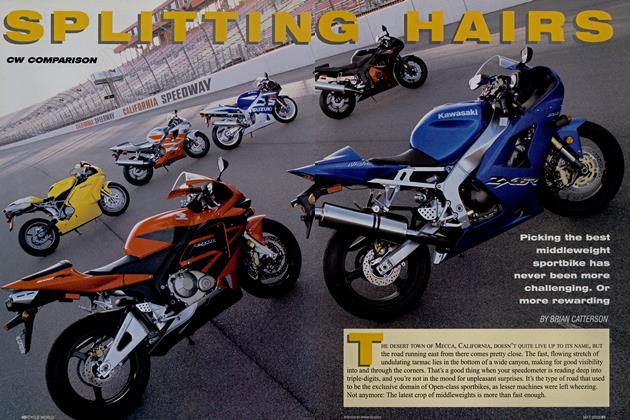

HONDA ST1100 VS. YAMAHA GTS1000

CW COMPARISON

YAMAHA'S FORKLESS WONDER TAKES ON THE KING OF SPORTTOURING

IS HAVING TUE TECHNOLOGICAL CAPACITY TO DO SOMEthing sufficient reason for doing it? Mostly, the answer is yes. The result is better communication, better transportation, better medical care. Also, more expensive communication, more expensive transportation, more expensive medical care.

So it is with motorcycles. The pair of sport-touring bikes you see here represents significant leaps in motorcycling sophistication and expense. Honda's ST 1100ABSTCS has proven itself over the past three seasons to be the premier example of its genre. It is a pleasing and effective mixture of highand low-tech that transforms any road, anywhere. anvtinie. into the sport-touring equivalent of Easy Street. It is not merely (`vele J4'orld s tavorite spoil-touring hike. It also was named by this magazine's editorial staff as the Best Touring Bike of 1992. beating out the heavier. plushier, more luxurious GL1500 Gold Wing for the honor.

The ST’s sport-touring crown is not assured, however, because Yamaha has entered the 1993 model year with the GTS1000A, which hop-scotches over several evolutionary steps to arrive at a design that is significant for at least two reasons. One, it is the first modem mass-produced motorcycle to offer an alternative to the telescopic fork. Two, it is the first production Japanese motorcycle to offer an electronic engine-management system that not only oversees and operates ignition and fuel-injection mapping, it does so in conjunction with a three-way catalytic converter that cleans up the engine’s exhaust.

The GTS isn’t completely unfamiliar. Its powerplant and rear suspension are derived from the FZR 1000. The swingarm and shock are straight off the FZR, but the engine is considerably altered. Bore and stroke remain 75.5 x 56.0mm for a displacement of 1002cc, but cam profiles have been altered, fuel injection substituted for carbs, exhaust headers reduced in dimension and made of single-wall tubing instead of the usual double-wall material, and the FZR’s EXUP exhaust powervalve replaced by the catalytic converter. The engine is tuned for midrange power instead of peak power; so inside the FZR-derived cases lives the same five-speed transmission found in the FZR.

The GTS’s engine doubles as a chassis component, adding rigidity to the two aluminum-alloy sideplates bolted to it. The front suspension is attached to the front of those sideplates, the rear to their rear. Everything else, including the abbreviated steering head, is carried by one of two subframes. If this sort of minimalist assembly sounds like a recipe for a lightweight bike, guess again. The GTS weighs 609 pounds dry, 103 pounds more than the FZR.

At that weight, however, it’s still lighter than the 686pound S T1 100. The ST is unusual only in that its swingarm has a single shock located on the right side. It uses a traditional tubular-steel frame and shaft-drive, and it is powered by a V-Four engine and five-speed transmission mounted longitudinally.

These two bikes may both be sport-touring bikes, yet they’re anything but birds-of-a-feather. The 1993 ST 1100, unchanged from last year, is a sport-touring bike, and as such, it offers a lot to like, including an engine that pulls like something that belongs under the hood of a John Deere, a comfortable, semi-upright riding position, a huge fuel tank and plenty of luggage capacity. Also unchanged is how well this large, heavy motorcycle works. Its engine lights up instantly without an undue display of cold-bloodedness, and it pulls through its five gears like a stallion, offering a wonderfully flat torque delivery, regardless of the gear selected or rpm showing. The ST will rev past its 8000-rpm redline, but its gear ratios are so well-chosen, and so much torque is available at lower rpm, there is no point in asking it to do so.

At the dragstrip, the ST powered through the quarter-mile in 12.20 seconds at 111.11 mph, and that kind of performance is just what the doctor ordered for working traffic. It’s also the right prescription when the going gets crooked, for when comers appear, this bike magically seems to shed some of its considerable bulk to become much more nimble than a bike this tall and top-heavy should be. Its steering is light and neutral, and its brakes fully up to whatever tasks are asked of them. The fork is not adjustable, so it’s convenient that Honda got the damping and spring rates right. At the rear, there’s preload and rebound-damping adjustment. Seating is very comfortable, with a wide, cushy seat, a slight forward lean to the shrouded tubular handlebar, and footpegs that are just moderately rearset.

If we have any complaints about the ST, they are that the bike’s windscreen causes considerable helmet buffeting, especially for tall riders, and that its seat foam packs down under heavy riders on very hot days. As for the rest of it, it’s a blast: You just crank it up, head it for the backroads, and ride comfortably at seven-tenths-maybe even seven-tenthsplus-to your heart’s content.

The GTS, meanwhile, is a bike of a different stripe. This is a sport-tourer. Sitting in its seat, one is struck by how aggressive the riding position is. The reach to the highmount clip-ons from the wide, firm seat is a long one over the tall, humped panel that shrouds the bike’s fuel tank-which is small enough to cause the reserve light to switch on after 135 miles of vigorous riding. Footpegs are relatively high and rearset.

The GTS’s semi-sportbike riding position is appropriate for the bike’s nature, though that nature is at first hidden by the engine’s docile behavior. Turn the key on, hit the switch, and the engine leaps to life without hesitation, the fuel-injection system’s computer automatically taking care of the enrichment required for cold-starts. That computer measures a number of parameters that include throttle position, intake air temperature and pressure, atmospheric pressure, coolant temperature, camshaft position and exhaust oxygen content. It then assigns values to what it learns from each of its sensors, crunches the numbers, then delivers to each cylinder precisely the air-fuel mixture that’s required. It works brilliantly to deliver the crisp throttle response we’ve come to associate with fuel-injected machines from BMW, Ducati and Bimota.

The engine begins making usable power at about 3500 rpm, but it is at 6000 rpm that Yamaha’s big Four comes alive with a sufficiently rich combination of horsepower and torque to smoke the ST in roll-ons, and to tour the quartermile in 11.66 seconds at 115.38 mph. Because the GTS’s engine is tuned for midrange, it pulls furiously until the tach needle reaches 8500 rpm. There, things flatten out a bit. A good shift point is 9000 rpm, for while the engine is redlined at 10,500, it isn’t pulling as hard at its upper limit as it is at 9000 rpm. While the GTS engine doesn’t deliver the FZR’s top-end surge, it is very strong in the midrange, and that makes it exciting to use.

The bike’s chassis adds to that excitement. The rear shock offers the same adjustments as the ST’s, and the front suspension offers spring preload, and compression and rebound damping. Once set up for weight, load and riding style, the GTS’s suspension is sporting-firm, instead of the ST1 l’s sporting-plush.

A ride on the GTS is very different from anything you’ve previously experienced. As you engage first gear and move off, you see that at driveway speeds the steering is heavy, with limited lock-to-lock movement. The heaviness disappears once you’re beyond a walking pace-though at all speeds the GTS requires heavier countersteering than the ST 1100 does-and you learn to live with the somewhat limited steering lock.

The RADD suspension system has other ways to remind you of its presence. The first thing you notice is a certain numbness through the handlebars. This slight numbness makes it difficult at first to feel what the front tire’s contact patch is doing. But the system does provides monster braking power, deep into comers, over all kinds of bumps. As a result, the bike invites the kind of heavy, late braking that would be very difficult, even perilous, to execute on a tele-forked bike. With the GTS, you can brake hard all the way into a comer’s apex. You also can brake hard over bumps; the front wheel doesn’t care. It doesn’t try to stand you up, put you down, or otherwise min your day. It just slows you down. Even during very hard sport riding, the single-front-disc, six-piston-caliper set-up exhibited no discernible fade, though testers did complain about the system’s lack of initial bite.

Late-braking antics bring out another of the GTS’s traits. Under heavy braking, the GTS’s steering takes a set, and to change line requires muscle. It helps to lighten up the brake load a little. This trait probably is at least partly a function of the front Dunlop radial’s profile and construction. It seems reasonable to assume that bikes like this won’t perform to the fullest measure until they roll on tires specifically designed for their alternative front suspensions.

A ride on the GTS makes you realize how much you rely on the quickened steering that results when a tele-forked bike dives under braking. Where the ST’s steering quickens up a bit as its fork compresses, the GTS’s steering gets heavier and doesn’t quicken. The difference is subtle, but very noticeable.

To use the GTS to full effect, you have to recalibrate your braking and turn-initiation techniques. Once you’ve done that, you find that, thanks to its sporting nature and stability, the GTS invites you to ride much more aggressively than you might aboard the STIL The ST, with its comfortable accommodations and torquey engine, is a natural for brisk, relaxed backroad travel. The GTS, with its stupendous midrange and generous ground clearance, calls out for the full-tilt boogie, without requiring some of the sacrifices in comfort such travel aboard a full-on repli-racer would require.

So, is Yamaha’s ability to make the GTS 1000 sufficient reason for building it? We’d have to say that it is, if only because it points the way toward production bikes of the future. At a time when the development of conventional motorcycle suspension is nearing the end of the line, there’s plenty of room for alternative systems, just as there’s plenty of room for expanded use of fuel injection. Does the GTS’s use of both make the it a better sport-touring bike than the ST, and does it “win” this comparison? No, it doesn’t, and no, it doesn’t. Use of these features merely makes the GTS different from the ST11-and for that matter, from nearly everything else. Both bikes brilliantly perform the task of sport-touring. Both are comfortable, both offer anti-lock braking and plenty of performance. One is a bit more aggressive than the other. One is a bit more comfortable than the other. And because of the remarkable attributes of each, each is a winner in its own right.

This pair is the Dream Team of sport-touring. Which of them would be better for you depends entirely upon your budget, your love of things high-tech, and your vision of sport-touring.

HONDA ST1100

$11,399

YAMAHA GTS1000

$12,999