Discoveries

UP FRONT

David Edwards

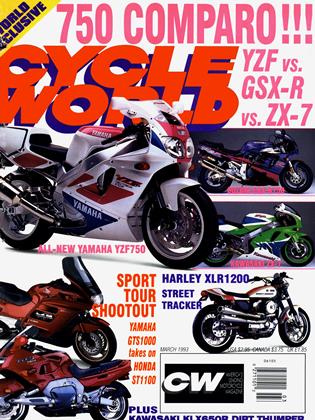

IT WAS AN AMBUSH OF PEARL HARBOR proportions. Throughout the '60s, '70s and early '80s, the motorcycle industry in America went from success to success, selling an ever-increasing number of bikes to an eager buying public. By 1984, $2 billion a year was being rung up through the sales of some 680,000 new motorcycles.

And then the roof fell in.

Blame it on the recession, blame it on the emergence of a no-risk society, blame it on overpricing and overspecialization of the motorcycles themselves, blame it on the insidious spread of couch-potatoism, but sales of new motorcycles went into a severe tailspin. By 1990, annual sales had plummeted to 265,000 units.

The manufacturers, especially the Japanese, accustomed to selling everything that popped off their assembly lines, were in a quandary. Ad campaigns were changed willy-nilly, without results. Honda, for years the industry leader, blundered badly by turning its back on the core group of enthusiasts and going after a non-existent group of yuppie-riders. Remember the ill-fated Pacific Coast 800 and the ads in Life magazine?

What was needed was a “spin doctor,” in the parlance of today’s politicos; a public-relations effort that would show motorcycling in a good light and help turn sales around. In 1986, industry representatives came together to discuss such a plan. What emerged was an embarrassment. First came a hacked-together PSA-public service announcement-a montage of mostly bad photos and worse words, published on donated pages in all the enthusiast magazines. This was followed by a misguided cross-country tour by four female motorcyclists, intended to get the general media’s attention. “Watch out, the next thing you know we’ll be getting the vote,” a friend of mine remarked at the time, mildly insulted, as many women riders were, that someone would deem it newsworthy that four females could ride 3000 miles across America all by themselves.

But from those first faltering steps has come success in the form of the Motorcycle Industry Council’s Discover Today’s Motorcycling awareness campaign. You probably know something about this program from the PSAs run in this and other motorcycle magazines. A toll-free telephone number (800/833-3995) is listed, which interested parties can call to get four free Straight Facts brochures that give an overview of motorcycling, a description of the various bike types, and information on financing and insuring motorcycles. Callers also are given the location of the nearest Motorcycle Safety Foundation RiderCourse.

In the three years the 800 number has been in operation, more than 65,000 calls have been logged, with some interesting results. A tracking of caller behavior shows that 81 percent visited a motorcycle dealership, and that 21 percent actually purchased a new or used bike, with a further 73 percent intending to purchase within two years.

As encouraging as those figures are, they don’t represent the DTM program’s most important work. This comes in the shadowy region of media relations, trying to subtly influence how newspapers, magazines, radio and television report on motorcycling. By researching the general media from 1986 through 1988, DTM officials found out that 89 percent of all motorcycle coverage was essentially negative. This was a time, you’ll remember, when everyone from headline-seeking senators to misinformed TV commentators was taking swipes at high-performance sportbikes. Add in the spillover from the three-wheel ATV controversy, plus Hollywood’s continuing fascination with bikers and babes, and all the ingredients for a public-relations nightmare were in place and up to speed.

“Media feeds media,” Beverly St. Clair Baird, DTM’s managing director, says. “Negativity tends to create more negativity.” But DTM struck back by sorting out those reporters and broadcasters nationwide who were negative to motorcycling and those who were neutral to positive. Serving as a media-relations clearing house, the DTM then provided those neutral-topositive types with facts that hopefully would result in positive stories. DTM also set itself up as an information bureau, a place where data-hungry reporters could turn to for quick answers. “DTM is very helpful, much more so than other motorcycling sources,” says Dick Stern, a writer for Forbes magazine. “Other sources are slow and unresponsive, which is unacceptable to a reporter on deadline.”

The strategy worked. Aided by Harley-Davidson’s increased popularity and the slew of accompanying “Born to be Mild” type of stories generated by all the rubbies-rich urban bikers-flocking to the sport, negative coverage of motorcycling dropped by one-third. More importantly, positive coverage bounded up by a factor of 13.

More good news comes from industry watchers, some of whom are predicting a significant upswing in new-bike sales for 1992. The figures aren’t fully compiled yet, but the increase probably will be close to 10 percent. Of course, DTM isn’t singlehandedly responsible for this turnaround, but it was a factor. “For the first time in a long time, there’s optimism,” says Doug Buemi, a communications consultant to DTM. “Motorcyclists are not a lonely, shrinking group anymore.”

In 1993, Discover Today’s Motorcycling, funded by the four Japanese bike-makers and BMW, plans to reach more callers than ever, and to get a new round of PSAs published in what is referred to as the “near-enthusiast” press-those publications that cover flying, scuba-diving, sailboarding, etc., whose activity-oriented readers are prime candidates to become riders.

Motorcycling is not out of the woods yet, but it’s good to have a team like DTM on our side.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue