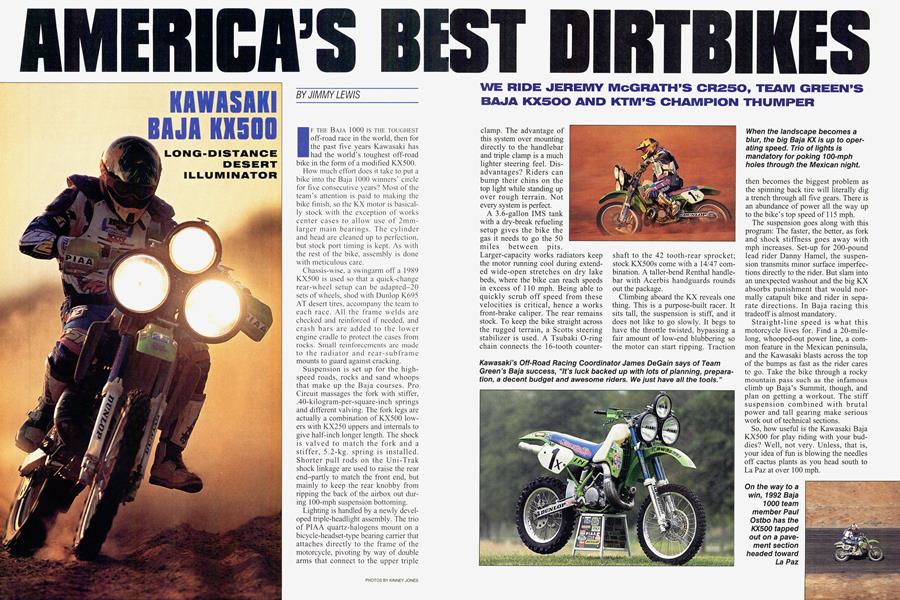

KAWASAKI BAJA KX500

AMERICA'S BEST DIRTBIKES

LONG-DISTANCE DESERT ILLUMINATOR

JIMMY LEWIS

IF THE BAJA 1000 IS THE TOUGHEST off-road race in the world, then for the past five years Kawasaki has had the world’s toughest off-road bike in the form of a modified KX500.

How much effort does it take to put a bike into the Baja 1000 winners’ circle for five consecutive years? Most of the team’s attention is paid to making the bike finish, so the KX motor is basically stock with the exception of works center cases to allow use of 2mm-larger main bearings. The cylinder and head are cleaned up to perfection, but stock port timing is kept. As with the rest of the bike, assembly is done with meticulous care.

Chassis-wise, a swingarm off a 1989 KX500 is used so that a quick-change rear-wheel setup can be adapted-20 sets of wheels, shod with Dunlop K695 AT desert tires, accompany the team to each race. All the frame welds are checked and reinforced if needed, and crash bars are added to the lower engine cradle to protect the cases from rocks. Small reinforcements are made to the radiator and rear-subframe mounts to guard against cracking.

Suspension is set up for the highspeed roads, rocks and sand whoops that make up the Baja courses. Pro Circuit massages the fork with stiffer, .40-kilogram-per-square-inch springs and different valving. The fork legs are actually a combination of KX500 lowers with KX250 uppers and internals to give half-inch longer length. The shock is valved to match the fork and a stiffer, 5.2-kg. spring is installed. Shorter pull rods on the Uni-Trak shock linkage are used to raise the rear end-partly to match the front end, but mainly to keep the rear knobby from ripping the back of the airbox out during 100-mph suspension bottoming.

Lighting is handled by a newly developed triple-headlight assembly. The trio of PIAA quartz-halogens mount on a bicycle-headset-type bearing carrier that attaches directly to the frame of the motorcycle, pivoting by way of double arms that connect to the upper triple clamp. The advantage of this system over mounting directly to the handlebar and triple clamp is a much lighter steering feel. Disadvantages? Riders can bump their chins on the top light while standing up over rough terrain. Not every system is perfect.

WE RIDE JEREMY McGRATH’S CR250, TEAM GREEN’S BAJA KX500 AND KTM’S CHAMPION THUMPER

A 3.6-gallon IMS tank with a dry-break refueling setup gives the bike the gas it needs to go the 50 miles between pits.

Larger-capacity works radiators keep the motor running cool during extended wide-open stretches on dry lake beds, where the bike can reach speeds in excess of 110 mph. Being able to quickly scrub off speed from these velocities is critical, hence a works front-brake caliper. The rear remains stock. To keep the bike straight across the rugged terrain, a Scotts steering stabilizer is used. A Tsubaki O-ring chain connects the 16-tooth counter-

shaft to the 42 tooth-rear sprocket; stock KX500s come with a 14/47 combination. A taller-bend Renthal handlebar with Acerbis handguards rounds out the package.

Climbing aboard the KX reveals one thing. This is a purpose-built racer. It sits tall, the suspension is stiff, and it does not like to go slowly. It begs to have the throttle twisted, bypassing a fair amount of low-end blubbering so the motor can start ripping. Traction

then becomes the biggest problem as the spinning back tire will literally dig a trench through all five gears. There is an abundance of power all the way up to the bike’s top speed of 115 mph.

The suspension goes along with this program: The faster, the better, as fork and shock stiffness goes away with mph increases. Set-up for 200-pound lead rider Danny Hamel, the suspension transmits minor surface imperfections directly to the rider. But slam into an unexpected washout and the big KX absorbs punishment that would normally catapult bike and rider in separate directions. In Baja racing this tradeoff is almost mandatory.

Straight-line speed is what this motorcycle lives for. Find a 20-milelong, whooped-out power line, a common feature in the Mexican peninsula, and the Kawasaki blasts across the top of the bumps as fast as the rider cares to go. Take the bike through a rocky mountain pass such as the infamous climb up Baja’s Summit, though, and plan on getting a workout. The stiff suspension combined with brutal power and tall gearing make serious work out of technical sections.

So, how useful is the Kawasaki Baja KX500 for play riding with your buddies? Well, not very. Unless, that is, your idea of fun is blowing the needles off cactus plants as you head south to La Paz at over 100 mph.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue