The technology of comfort

LEANINGS

peter Egan

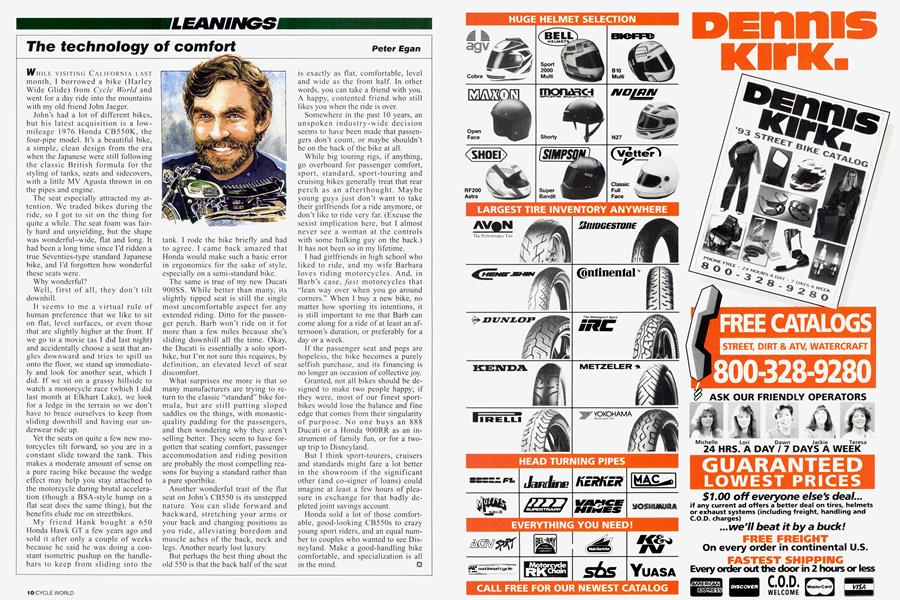

WHILE VISITING CALIFORNIA LAST month, I borrowed a bike (Harley Wide Glide) from Cycle World and went for a day ride into the mountains with my old friend John Jaeger.

John’s had a lot of different bikes, but his latest acquisition is a lowmileage 1976 Honda CB550K, the four-pipe model. It’s a beautiful bike, a simple, clean design from the era when the Japanese were still following the classic British formula for the styling of tanks, seats and sidecovers, with a little MV Agusta thrown in on the pipes and engine.

The seat especially attracted my attention. We traded bikes during the ride, so I got to sit on the thing for quite a while. The seat foam was fairly hard and unyielding, but the shape was wonderful-wide, flat and long. It had been a long time since I’d ridden a true Seventies-type standard Japanese bike, and I'd forgotten how wonderful these seats were.

Why wonderful?

Well, first of all, they don’t tilt downhill.

It seems to me a virtual rule of human preference that we like to sit on flat, level surfaces, or even those that are slightly higher at the front. If we go to a movie (as I did last night) and accidentally choose a seat that angles downward and tries to spill us onto the floor, we stand up immediately and look for another seat, which I did. If we sit on a grassy hillside to watch a motorcycle race (which I did last month at Elkhart Lake), we look for a ledge in the terrain so we don’t have to brace ourselves to keep from sliding downhill and having our underwear ride up.

Yet the seats on quite a few new motorcycles tilt forward, so you are in a constant slide toward the tank. This makes a moderate amount of sense on a pure racing bike because the wedge effect may help you stay attached to the motorcycle during brutal acceleration (though a BSA-style hump on a flat seat does the same thing), but the benefits elude me on streetbikes.

My friend Hank bought a 650 Honda Hawk GT a few years ago and sold it after only a couple of weeks because he said he was doing a constant isometric pushup on the handlebars to keep from sliding into the tank. I rode the bike briefly and had to agree. I came back amazed that Honda would make such a basic error in ergonomics for the sake of style, especially on a semi-standard bike.

The same is true of my new Ducati 900SS. While better than many, its slightly tipped seat is still the single most uncomfortable aspect for any extended riding. Ditto for the passenger perch. Barb won’t ride on it for more than a few miles because she’s sliding downhill all the time. Okay, the Ducati is essentially a solo sportbike, but I’m not sure this requires, by definition, an elevated level of seat discomfort.

What surprises me more is that so many manufacturers are trying to return to the classic “standard” bike formula, but are still putting sloped saddles on the things, with monasticquality padding for the passengers, and then wondering why they aren’t selling better. They seem to have forgotten that seating comfort, passenger accommodation and riding position are probably the most compelling reasons for buying a standard rather than a pure sportbike.

Another wonderful trait of the flat seat on John’s CB550 is its unstepped nature. You can slide forward and backward, stretching your arms or your back and changing positions as you ride, alleviating boredom and muscle aches of the back, neck and legs. Another nearly lost luxury.

But perhaps the best thing about the old 550 is that the back half of the seat is exactly as flat, comfortable, level and wide as the front half. In other words, you can take a friend with you. A happy, contented friend who still likes you when the ride is over.

Somewhere in the past 10 years, an unspoken industry-wide decision seems to have been made that passengers don’t count, or maybe shouldn’t be on the back of the bike at all.

While big touring rigs, if anything, go overboard for passenger comfort, sport, standard, sport-touring and cruising bikes generally treat that rear perch as an afterthought. Maybe young guys just don’t want to take their girlfriends for a ride anymore, or don’t like to ride very far. (Excuse the sexist implication here, but I almost never see a woman at the controls with some hulking guy on the back.) It has not been so in my lifetime.

I had girlfriends in high school who liked to ride, and my wife Barbara loves riding motorcycles. And, in Barb’s case, fast motorcycles that “lean way over when you go around corners.” When I buy a new bike, no matter how sporting its intentions, it is still important to me that Barb can come along for a ride of at least an afternoon’s duration, or preferably for a day or a week.

If the passenger seat and pegs are hopeless, the bike becomes a purely selfish purchase, and its financing is no longer an occasion of collective joy.

Granted, not all bikes should be designed to make two people happy; if they were, most of our finest sportbikes would lose the balance and fine edge that comes from their singularity of purpose. No one buys an 888 Ducati or a Honda 900RR as an instrument of family fun, or for a twoup trip to Disneyland.

But I think sport-tourers, cruisers and standards might fare a lot better in the showroom if the significant other (and co-signer of loans) could imagine at least a few hours of pleasure in exchange for that badly depleted joint savings account.

Honda sold a lot of those comfortable, good-looking CB550s to crazy young sport riders, and an equal number to couples who wanted to see Disneyland. Make a good-handling bike comfortable, and specialization is all in the mind.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue