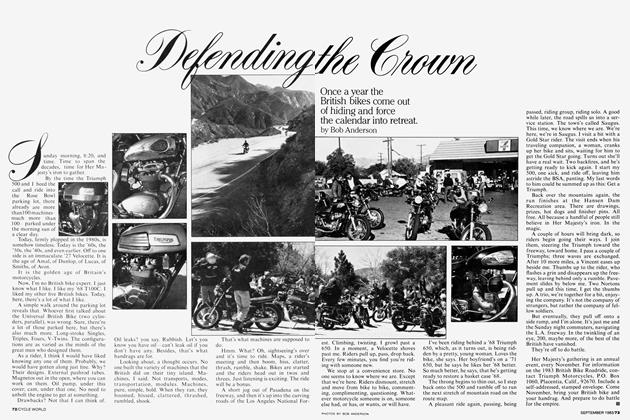

A Highly Moveable Feast

MOUNTAIN HIGHS: CYCLE WORLD'S GP EURO-TOUR OF THE ALPS

PETER EGAN

LET’S FACE IT. MANY OF US HAVE doubts about guided bike tours.

Will the group travel too slowly? Too fast? Will we

spend valuable hours of riding daylight waiting at gas stations watching each other fill-up, search for dropped gloves or struggle with mechanical problems? Will we be forced to stop for every cathedral, or, worse, tour the dreaded Gingham Doll Museum?

Wouldn’t it be cheaper, faster and

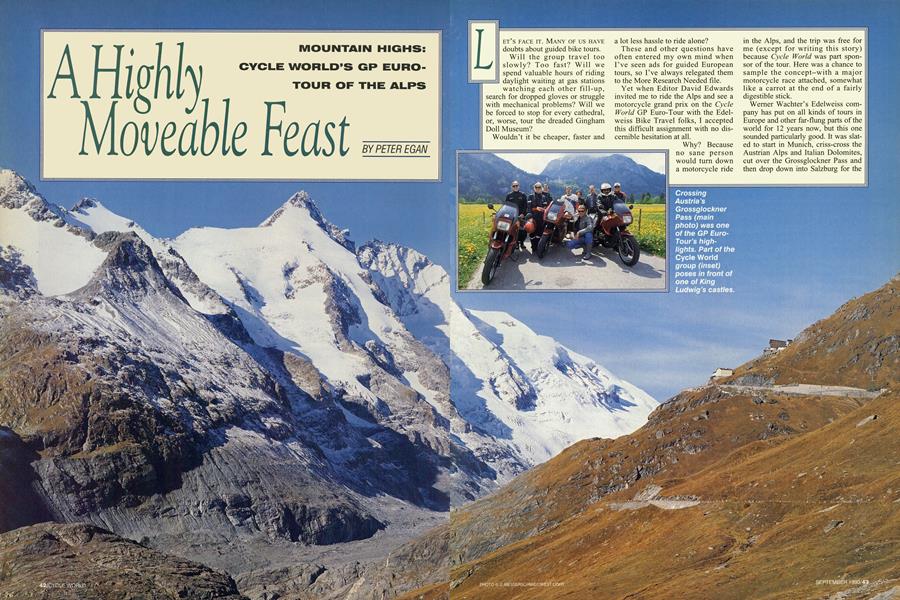

Why? Because no sane person would turn down a motorcycle ride a lot less hassle to ride alone? Werner Wachter’s Edelweiss company has put on all kinds of tours in Europe and other far-flung parts of the world for 12 years now, but this one sounded particularly good. It was slated to start in Munich, criss-cross the Austrian Alps and Italian Dolomites, cut over the Grossglockner Pass and then drop down into Salzburg for the Grand Prix of Austria at the famous Salzburgring racetrack.

These and other questions have often entered my own mind when I’ve seen ads for guided European tours, so I’ve always relegated them to the More Research Needed file.

Yet when Editor David Edwards invited me to ride the Alps and see a motorcycle grand prix on the Cycle World GP Euro-Tour with the Edelweiss Bike Travel folks, I accepted this difficult assignment with no discernible hesitation at all. in the Alps, and the trip was free for me (except for writing this story) because Cycle World was part sponsor of the tour. Here was a chance to sample the concept-with a major motorcycle race attached, somewhat like a carrot at the end of a fairly digestible stick.

Alpine roads and GP bike racing; a hard combination to beat.

Cost of this trip (to non-journalists) was $2795, to include round trip air fare from New York to Munich, seven nights lodging in a double room, all breakfasts and dinners, motorcycle rental and $650 deductible insurance, luggage transport, a tour guide on motorcycle and tickets for the Austrian GP.

For an extra $1995 you could bring along a passenger/roommate, and for various amounts of money ($125 to $250) you could upgrade your bike from a Suzuki VX800 to an 1100 Katana, a BMW K75, Kl 100RS, K1100LT, R100GS, or R100GS Paris-Dakar. They even managed to get one of the first RI 100RS Boxers for this trip.

In other words, everything would be covered but lunches, fuel and bar tabs for drinks and coffee, which we were warned could eat up another $50 or so per day. Europe, after all, is the land of the $20 motorcycle fill up; gasoline costs about as much as good Bavarian beer. ____________

J ust before the trip, I called David, who's been on a few of these tours before, to ask what kind of riding gear I should bring.

■‘I’m bringing everything.” he said. “Filling up my equipment bag with gear. They have a luggage van, so you don’t have to carrv anything on the

bike if you don't want to, and you never know what the mountains are going to be like in May. Better to be safe than sorry.”

Wow! A motorcycle trip without luggage limits.

So I got out my Hindenburg-class Hondaline duffel bag and stuffed it

with every kind of jacket, boot and rainsuit I own, plus a large suitcase for regular clothes (barwear). Fully packed, neither bag could be elevated by a lone human without resort to wedges, blocks and tackles or some other cheap trick from your high school Physics text, so Barb (who unfortunately had to work at a real job and could not go on this trip) helped me carry the baggage to the airline counter.

I flew over on British Airways, Chicago-London-Munich, an excellent flight that lasted two movies, four meals, two glasses of red wine, three bike magazines and one nap. We landed in Munich at dusk with the sun just breaking through a passing line of spring thundershowers. A warm, beautiful evening in Munich.

Normally the Edelweiss van picks you up at the airport, but David and I came in a day early, so I had to find my own way to our hotel in Saurlach, a village just south of Munich, by train. A couple of German teens who spoke better English than our local Eyewitness News Team, and with fewer grammati-

cal errors, cheerfully explained the train system and ticket machine, and I was on my way. One switch in downtown Munich, five stops south and I detrained in the quiet little burg of Saurlach. I carried my luggage three blocks to the hotel and arrived somewhat beat and long of arm. Mr. Edwards, they said, had already checked-in and was in his room recuperating from his own luggage.

Gear stowed, we had a beer in the hotel bar and met one of our two tour guides, a friendly, easy-going Austrian named Josef Vielhaber, then checked out our bikes in the back parking lot. David would be riding an R100GS Paris-Dakar and I had a K75S.

Next morning, we fired up the bikes and rode into downtown Munich, parked at the edge of the old city center and headed off on foot in search of one of my favorite places remembered from a trip 20 years ago, a huge beer hall called the Hofbrauhaus.

Munich is a lovely old city, much rebuilt to original specs after the war. It is a town designed around the principle that civilized people are intended to spend as much time as possible sitting in gardens and outdoor cafés, talking and drinking immense steins of beer and eating pretzels the size of lawn furniture while surrounded by trees, flowers and charming architecture.

David and I did just that for most of the afternoon. After solving all the problems of the world and motorcycle design, we headed off to the hotel to meet our incoming riders.

Interesting mix. We met Norm, a 50-ish former Triumph and Indian dealer from Michigan; two riding buddies named Tony and David from the Twin Cities, who normally rode their ZX-11 and 900RR on the weekends; two thirty-something couples, Bill and Rosalie and Doug and Lori from Pennsylvania, who had found baby-sitters for their young children; John, a machinist from Illinois; Max, a flying instructor from Florida; Rich, an aerospace worker from Pennsylvania; Jason, a young Houston banker and motocrosser, boyhood friend of and sometime crew member for Kevin Schwantz, no less; Luther, another vacationing guy from Houston; Bob, a mid-40s businessman and FZR400 club racer from Indianapolis; Wes, a young American exMarine who lived in Germany with his German wife and worked at a foundry; Andrew, a tall aviation mechanic from Arizona, by way of California; and Martin and Ellen, a globe-trotting middle-aged couple from New Jersey who own their own plumbing business.

We also met our other guide Josef, last name Hackl, a very funny bearded fellow who moonlights (daylights?) as a chef when not leading group tours.

A fter dinner on Sunday night, the two Josefs explained the drill. No one had to follow any set plan. As long as you could find the next night's hotel by dinnertime, you were free to ride alone, in small clumps or with the tour guide. If you were going to be late for dinner, call the hotel to prevent the formation of posses and search parties. Most of us decided, however, to follow the guides, since they had laid out the best roads on the map and also knew where they were going.

Monday morning we mounted up on our Suzukis and BMWs and headed out toward the looming, whitecapped Alps, which are only an hour’s ride south of Munich.

From the beginning, the roads were smooth, winding and just plain beautiful, and in that first morning I made two discoveries. First, our guides were excellent riders; second, the members of our group were also good riders, much quicker than I’d expected. There would be no boredom riding with this batch. Perhaps the GP angle of the trip had brought out the sporting wing of the sport-touring crowd.

Take Martin and Ellen. Good solid citizens from New Jersey, two up on a big Kl 100RT, complete with travel trunk. As we left the hotel I said to myself, “Well, I’ll certainly have to get around this obviously mature, sane couple and get up in front with the faster solo riders like me.”

An hour later, I was still wringing out my K75S to keep up with Martin and Ellen. Martin was smoking the brakes into comers and occasionally sliding both ends of the bike in damp hairpin turns while Ellen pointed out scenic castles and churches for the rest of us. “Good grief,” I said inside my helmet. “Who are these guys?”

At a coffee break, someone said to Ellen, “Aren’t you nervous, riding that fast on the back of a bike?”

She shook her head. “Martin never crashes, and it’s in my marriage contract that I have to be serene on the back of a fast bike. Actually, Marty’s slowed down a lot from the way we used to ride.”

Martin, it turned out, raced enduro bikes for 25 years and won several East Coast championships.

And so it went with the whole group. We had enduro riders, motocrossers, roadracers and street riders of long experience. Everyone rode well together, and quickly. Maybe a little too quickly at times.

That first morning, the group spirit took hold and everyone was pushing fairly hard through a wooded downhill just before the Austrian border. One solo rider went wide in a curve, clipped a tree and fell down. He was unhurt, but his handlebars and pegs were bent and one saddlebag was skimmed off. We bent things around and got him back on his bike, but everyone slowed down a notch. A warning shot across the bow.

I won’t retrace every loop and turn of our ride for the next four days, except to say that we worked our way through half a dozen passes in the Alps in a series of sweeping cloverleaf routes that took us back and forth across the

borders of Germany, Austria, Italy and Switzerland, and to make a few general observations on the ride:

1. Border crossings, in the new spirit of the European Community, are now infinitely easier than they were just a few years ago. Most of the time you are just waved through the customs gates, no passport checks, no questions, no stopping. Makes you realize what a waste of time the old system was.

2. Roads in the Alps are almost uniformly smooth and in wonderful repair, the only surprises being an occasional patch of brick pavement in high mountain hairpins. The Austrians send out road crews every morning to sweep up dust, sand and fallen rock, and even have a buffer machine that polishes the roadside reflectors. Europe apparently spends

its tax money on useful services for its citizens, who originally paid the money. What a system.

3. People everywhere on the route were friendly and helpful. Most spoke either perfect English or some English, or did the best they could with sign language. Everyone was cheerful. Must be the scenery and the mountain air.

4. The scenery and the mountain air are terrific. You come through an idyllic mountain pass ringed

with glaciers and jagged peaks and look out on 20 or 30 miles of smooth, serpentine mountain road that descends into a green valley of forests, fields, small villages with red tile roofs and soaring church spires, neat farms, wood fences, orchards and brown cows. Repeat as necessary, or every half hour if you keep riding. The beauty just goes on and on. And on. If there is a bad or ugly road anywhere in the Alps, it is apparently well hidden behind a large painted backdrop that looks exactly like the aerial opening shot from the Sound of Music.

5. The hotels and restaurants chosen by the Edelweiss are small, friendly, clean and charming, usually in tiny, picturesque villages. Not overdone five-star, $400-a-night luxurious, but exactly the kind of place you would be looking for (but might not find) if you were traveling on your own. The food at all our stops was excellent. Good regional cooking, without the heartbreak of weight loss.

6. Having navigated much of Europe by car alone and with various co-drivers, it was an immense relief to follow a guide who knows where he’s going. We could enjoy the scenery and the riding without having to stop at every intersection and Y in the road for a short argument and fistfight followed by the inevitable wrong tum and later recriminations or divorce proceedings.

7. Not having to search every evening for a good quality (yet affordable) hotel and restaurant is also a relief. When you travel alone, it behooves you to begin this search by late afternoon lest you be aced out of the last vacancy in town and end up riding half the night in a rainstorm with no dinner, as Barb and I did in the Canadian Rockies last year.

8. It is much more fun to spend an evening on the road with 15 or 20 other committed (certifiable) motorcyclists than it is to share a bar and restaurant with one grumbling alcoholic and a retired couple from Moline who just had new pinstriping put on their Winnebago motorhome. The whole trip becomes a kind of traveling celebration, the original moveable feast.

9. After a hard day of riding, beer is good. Especially Stiegl pilsner, “Das Salzberger Bier.” Not only is it good, but it may actually be The Good, that elusive object of so much philosophical searching and debate.

The Good is served in half-liter steins that bring wisdom and then, later, sleep.

10. I brought way too much luggage. Dress is casual every nightboots, jeans and a sweater work fine for the whole trip. On the road, most people got by with street leathers-or jeans and a leather jacket-and a rainsuit. A few of us, on the cooler, highmountain days, wore Aerostitch suits, which also seemed to handle the varied weather well. It rained on us twice during the week, but for only part of the day.

Back through to the the road. spectacular After jutting a loop rock formations of the Italian Dolomites and an ascent up the Grossglockner Pass, Austria’s highest, we descended on Salzburg for the GP, staying at an outlying hotel not far from the beautiful Salzburgring.

Most of us took the train into Salzburg for a day of hiking around Mozart’s home stomping grounds. Salzburg is a small, walkable city of great charm, built against the cliffs of a bend in the River Salzach, with a huge medieval fortress towering over it. David and I noted that the old sections on both sides of the river were surrounded by high security walls and guard posts, a practice that is just now being reintroduced to parts of Los Angeles.

Early Sunday morning we joined the thousands of bikes streaming toward the Salzburgring, made our

way to a prime section of hillside staked out for us by our Edelweiss guides-though there really are no bad seats in this natural amphitheater of a race circuit-and sat down to watch the 125, 250 and 500cc races.

Those who follow the sport already know that Kevin Schwantz won the 500. Schwantz is immensely popular in Europe, and when he surged into the lead the crowd went crazy. On his victory lap, someone handed him a huge American flag on a pole, and he

toured the track with the Stars and Stripes trailing behind him, to thunderous applause from the mostly German, Austrian and Italian crowd. This would never have happened when I was here 20 years ago, and it was a fine thing to see.

After the race, we thronged our

way back to Munich in the late afternoon sun and got together for one last group dinner before everyone flew home to the States in the morning.

After dinner, we toasted the two Josefs for their great job of guiding, and then someone proposed a reunion tour next year. Someone else suggested a ride to the German GP or the Isle of Man. There seemed to be a consensus among all, including me, that this was an excellent idea. And I think it could happen. You make good friends when you ride for a week.

It is hard to say this without seeming to pat yourself inclusively on the back, but it seems to me that those who have enough gumption and sense of adventure to travel far from home, and insist on riding motorcycles when they get there, are almost always fun, interesting people. The civilian version of a few good men, and women.

If this bunch shows up for another tour-of the Alps or of anywhere else—I’ll try to be there. With Barb, I hope. Trips like these are better shared than described, and even better lived than remembered. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

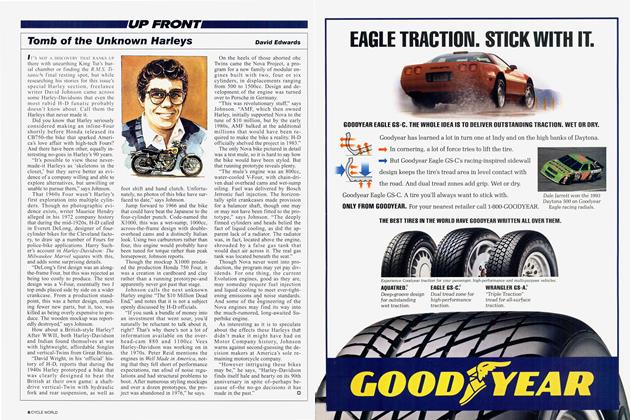

Up Front

Up FrontTomb of the Unknown Harleys

September 1993 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsDo Loud Pipes Save Lives?

September 1993 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCVicious Cycles

September 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1993 -

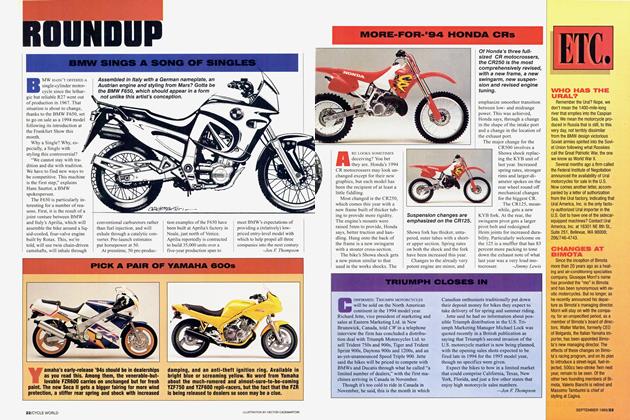

Roundup

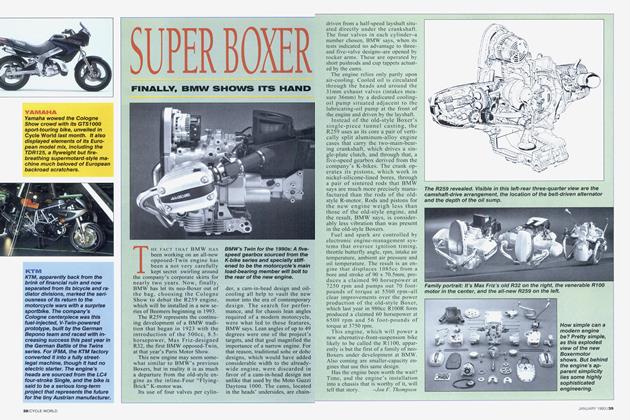

RoundupBmw Sings A Song of Singles

September 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupPick A Pair of Yamaha 600s

September 1993