Future shock

AT LARGE

Steven L. Thompson

WHEN THEY LAUGHED AT ME IN THE repair center. I knew I was in for a long ride. Sure, the Toshiba PI 350 dot-matrix printer I thunked down on the computer wizard’s fixit counter was about six years old, but 1 couldn’t see why that would make the guy laugh when I told him 1 wanted to repair it. I mean, before it suddenly went bonkers, this thing had spit out four novels and more magazine stories, letters, memos, and envelopes than I could ever count. So 1 was not amused when he smirked and called the other wizards over to look at a printer that had lasted six whole years, and then told me that I was nuts to want to repair something that old.

At last count, there were at least six, maybe seven, Q-W-E-R-T-Y . . . keyboards around my house. The oldest is built into a 60-year-old Underwood forged from Indestructium, given to me by a fellow novelist, the newest is umbilicaled to a CPU with more RAM and a faster processor than most small animals, and in between are various other computers, and typewriters that wall die only when brutally murdered. Being a wordsmith requires this kind of backup, I’ve found. So when a guy tells me a six-year-old printer that dotmatrixed at least one best-seller is that old, I get miffed. I told him to troubleshoot it anyway.

He did. Diagnosis: “What you need,” he said, “is a laser printer. Like the Hewlett-Packard III. Which I can sell you tomorrow, so you can finish your book.”

Not having fallen off the turnip truck yesterday, I asked other wizards for their opinions. They didn’t laugh, but none could understand why I'd w'ant to sink even so much as a nickel into something that old. So 1 caved in and bought a nice new H-P III and finished the book.

But the Toshiba didn't go into the trash can. It waited until I had time to open it up and see for myself. It helped that the workshop where I unraveled its mysteries held not only the Kenwood receiver I bought in 1970, and which still works beautifully, but also a 1969 Yamaha TD2, which also worked beautifully, last time I rode it. in 1982. Suitably forti-

fied by other well-designed Japanese stuff, I persevered and found out that, indeed, the serial circuit was not happy. But there was a fix, albeit expensive, so soon, the PI 350 will again turn dots into words for me. In spite of the so-called wizards.

They weren't wrong, of course. The laser printer is a huge improvement over the dot-matrix. And there's no way I can really justify putting untold hours and more bucks into the old printer. Except for the technical sweetness of the thing. The same technical sweetness that keeps us repairing and tinkering with old bikes and cars. When I peeled off the cover of that printer, I w'as looking at truly elegant engineering. I could no more toss it away than I could that one-ton Underwood or the TD2.

But as I thought about the speed of innovation in the infobiz, and compared it with motorcycles, 1 realized w hat had been bugging me for about five years—the lifespan of the PI 350. It was this: In motorcycles, compared with computers, not a lot has happened, innovation-wise.

When I think about motorcycling this way, as engineering rather than marketing, I begin to think that, just maybe, sales of bikes have slumped not because of too much innovation in a traditional and conservative avocation, but because of too little.

This is not a new criticism of motorcycling. When iconoclastic British writer Len Setright wrote, about a decade ago, of his disgust upon discovering that most of his motorcycling colleagues did not share his zest for “real improvement” of motorcy-

cles, but wanted only a “good old wrestle” with a beast they understood, many of those who worked in the world of concern for such things agreed, secretly if not openly. Maybe motorcyclists really were the Neanderthals of the motorhead world, they muttered. Motorcyclists might really be more interested in tribal displays than in quantum leaps in their two-w'heelers.

The issue Setright raised was drowned almost immediately by the noise of the new toys at the beginning of the ’80s. We were deluged with new' engine configurations, staggering jumps in raw performance and a model and marketing blitz that left a lot of us media-stunned if not futureshocked, reeling and wondering to which “niche” we now' belonged.

But after five years of slumping sales, the noise is muted. And what’s d i fie rent, now that the latest showroom ploy is to take us, via standardstyle bikes, back to the future? We’ve got cleaner-burning, smoother, more powerful engines, better brakes and suspensions, much better tires, and a lot more warnings and plastic plastered all over the machines. Yes, our thinly disguised production racersare easier than ever to take faster than ever around racetracks, and dirtbikes now wear stuff that used to only be seen on streetbikes. BMW will sell you ABS, Honda will sell you a Gold Wing with reverse, but that’s about it. breakthrough-wise.

If the computer biz were in this state, my poor old Toshiba w'ould still be leading-edge stuff. Not even the car business is as stuck in the mud as bikes are. In Bad-Bad-Biketown, we’re still debating whether decadesold “breakthroughs” like hub-center steering “belong” on a motorcycle, while smart car guys in Detroit and Osaka and Stuttgart are running around in seriously sci-fi devices, powered by everything from hydrogen to the sun. And what near-term developments do we see for motorcycles?

Well, I understand this year's crop of wonderbikes includes more upside-down forks.

Not, presumably, made by Toshiba. Unless they've found a new way to recycle old printers. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontNote To Edgar

March 1991 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsShould You Buy An Italian Bike?

March 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1991 -

Roundup

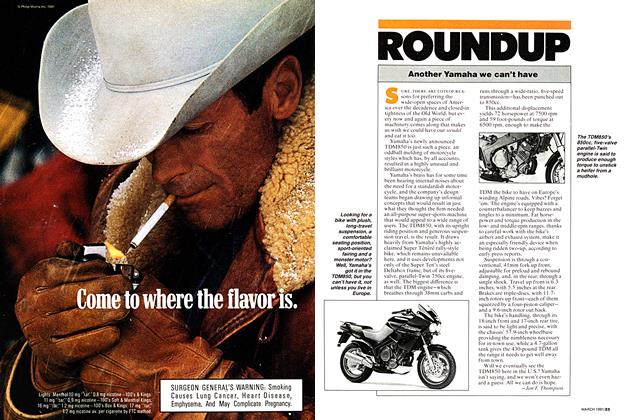

RoundupAnother Yamaha We Can't Have

March 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupLaverda Gsx-R: Italy's Orient Express

March 1991 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupIntruder 1400 Big Twin, Suzuki-Style

March 1991 By Ron Griewe