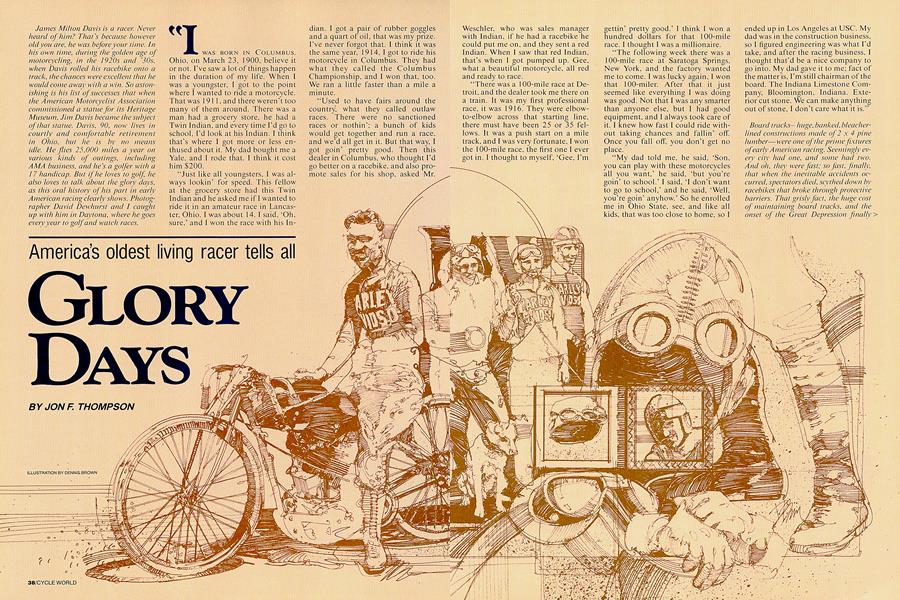

GLORY DAYS

America's oldest living racer tells all

JON F. THOMPSON

James Milton Davis is a racer. Never heard of him? That's because however old you are, he was before your time. In his own time, during the golden age of motorcycling, in the 1920s and '30s. when Davis rolled his racebike onto a track, the chances were excellent that he would come away with a win. So astonishing is his list of successes that when the American Motorcyclist Association commissioned a statue for its Heritage Museum, Jim Davis became the subject of that statue. Davis, 90, now lives in courtly and comfortable retirement in Ohio, but he is by no means idle. He flies 25,000 unites a j'ear on various kinds of outings, including AMA business, and /ie's' a go~fer wit/i a 17 handicap. But if/ic loves to go~f lie also loves to talk about tile glori' days. as this oral history of/i/s part in ear/v A u;ierican racing cleari~i' shows. Pholog rap/icr David Dewhurst and I caught up wit/i him in Daytona, where lie goes evemy year to golf and v~'atc/i races.

I WAS BORN IN COLUMBUS. Ohio, on March 23, 1900. believe it or not. I've saw a lot of things happen in the duration of my life. When I was a youngster, I got to the point where I wanted to ride a motorcycle. That was 1911. and there weren't too many of them around. There was a man had a grocery store, he had a Twin Indian, and every time I'd go to school. I'd look at his Indian. I think that's where I got more or less en thused about it. My dad bought me a Yale. and I rode that. I think it cost him $200.

"Just like all youngsters. I was al ways lookin' for speed. This fellow at the grocery store had this Twin Indian and he asked me if I wanted to ride it in an amateur race in Lancas ter, Ohio. I was about 14. 1 said, `Oh, sure,' and I won the race with his Indian. I got a pair of rubber goggles and a quart of oil, that was my prize. I've never forgot that. I think it was the same year, 1 9 1 4, I got to ride his motorcycle in Columbus. They had what they called the Columbus Championship, and I won that, too. We ran a little faster than a mile a minute.

"Used to have fairs around the countr~ what they called outlaw races. There were no sanctioned races or nothin': a bunch of kids would get together and run a race, and we'd all get in it. But .that way, I got goiri' pretty good. Then this dealer in Columbus. who thought I'd go better on a racebike, and also pro mote sales for his shop, asked Mr. Weschler, who was sales manager with Indian, if he had a racebike he could put me on, and they sent a red Indian. When I saw that red Indian, that’s when I got pumped up. Gee, what a beautiful motorcycle, all red and ready to race.

“There was a 100-mile race at Detroit, and the dealer took me there on a train. It was my first professional race, it was 1916. They were elbowto-elbow across that starting line, there must have been 25 or 35 fellows. It was a push start on a mile track, and I was very fortunate, I won the 100-mile race, the first one I ever got in. I thought to myself, ‘Gee, I'm gettin’ pretty good.’ I think I won a hundred dollars for that 100-mile race. I thought I was a millionaire.

“The following week there was a 100-mile race at Saratoga Springs, New York, and the factory wanted me to come. I was lucky again, I won that 100-miler. After that it just seemed like everything I was doing was good. Not that I was any smarter than anyone else, but I had good equipment, and I always took care of it. I knew how fast I could ride without taking chances and failin’ off. Once you fall off, you don’t get no place.

“My dad told me, he said, ‘Son, you can play with these motorcycles all you want,’ he said, ‘but you’re goin’ to school.’ I said, i don’t want to go to school,’ and he said, ‘Well, you’re goin’ anyhow.’ So he enrolled me in Ohio State, see, and like all kids, that was too close to home, so I ended up in Los Angeles at USC. My dad was in the construction business, so I figured engineering was what I’d take, and after the racing business, I thought that’d be a nice company to go into. My dad gave it to me; fact of the matter is, I'm still chairman of the board. The Indiana Limestone Company, Bloomington, Indiana. Exterior cut stone. We can make anything out of stone. I don’t care what it is.’’

Board trackshuge, banked, bleacherlined constructions made of 2 x 4 pine lumber—were one of the prime fixtures of early American racing. Seemingly every city had one, and some had two. And oh, they were fast; so fast, finally, that when the inevitable accidents occurred, spectators died, scythed down by racebikes that broke through protective barriers. That grisly fact, the huge cost of maintaining board tracks, and the onset of the Great Depression finally > put the board tracks out of business. But Davis remembers them well.

"MY FAVORITE TRACKS were board tracks. They were clean, and you could put a white shirt on, fact of the matter was, I'd ride with a white shirt and a damned gold polkadot tie. They were clean, they were fast. 'Course a lot of the wood, splinters and things, would fly and you'd get hit with quite a few of those. I run one through my foot and out the other side during a race. And it happens so quick, you don't even know it. This piece was bigger than a pen cil, about a foot long. It went through my foot and knocked the pedal off the machine. I knew something had happened, but I didn't know what it was. They took me to the hospital af ter the race and they asked me, should they pull it out or cut it out? They asked me! I said that was their business, I didn't know. But they did pull it out, swished it all out with some kinda medicine, I dunno what it was. I walked on crutches for maybe a couple of weeks or more be fore I could go on again. I went to races, though, that way. One of the promoters said, when I walked in his office, `Are you gonna ride?' I said, `Certainly! I don't push it, I ride it.' Hah! We got paid $250 appearance money. you know, to go to a race. I'd ride maybe one lap, get my appear ance money, then I'd call that a ride, that's all I had to do. Appear, run a lap, then they'd pay me. That foot stayed with me for almost a whole season before it got so I could use it, before it healed properly."

If Davis was adept at manipulation of a racebike, he also was adept at manipulating promoters and sanction ing bodies. His goal in these manipula tions? To race. Always, to race.

"WHEN WE WENT WEST the first time in `20, I got Suspended for a year. The Indian factory shipped two race machines out to Phoenix for me to ride. The referee said to me when I got out there, `You can't ride here.' I said, `Well, why not?' He said, `They've already picked the riders.' I said, `Why, that can't be. Why would the factory ship two machines out here for me to ride?' The ruling they made was they were gonna start two Excelsiors, two Harley-Davidsons and two Indians, which was six riders. Well, I wasn't there at all. So I said to the referee, `Well, now, if I get a wire from the Motorcycle and Allied Trades Asso ciation (the forerunner of the AMA) in Chicago, can I ride?' And he said yes, I could. So I went down to the Western Union in Phoenix, and I asked the young girl there if she would make me up a phony telegram. She said she wasn't allowed to do that, and I said, `Well, would you do it for a box of candy? I'll buy you a box of chocolate candy.' She said, `What do you want in it?' So I made up a letter. I said, `Permit Jim Davis to ride, letter following.' I had this little kid on a bicycle bring this tele gram up to me. I'm all ready to race. I'd practiced and got all ready to go, see, and I brought this telegram up, and the referee looked at it and said I could ride. They had four events there, and the way it ended up, I won the four events. The factory shipped me out there to win something. Then I went on to Los Angeles to ride at Ascot, and when I got out there, the referee said, `You can't ride here, we got a letter sayin' you been sus pended.' It was for that business in Phoenix.

"They used to have outlaw races, a bunch of kids would get together and run a race."

"That's when I left Indian. I quit, I was suspended for a year. Mr. Ray Werschaur with Harley, he said, `Why don't you ride Harley?' I said, `Well, I'm suspended for a year,' and he said, `Don't let that worry you.' I don't think I was out of a job for two or three days. Harley took me on, and they must have done something in Chicago, because they lifted my sus pension right away. Because Harley Davidson kept the M and ATA goin' ."

The most classic of classic match ups? Just this. Harley vs. Indian, In dian vs. Harley Davis rode both. Ah, but which did he prefer? Thai depended on the offei~

"I JUMPED BACK AND FORTH BEtween Harley and Indian. Whichever one would give me the most money, that's where I went. I'd ride the big money, I didn't care what it was. Har ley-Davidson, they didn't care if whether it was my name or who won, they wanted Harley to win. When they'd publicize a race, it was `Har ley-Davidson Wins,' not Jim Davis or Ralph Hepburn-they didn't care about your name. As long as I was gonna ride, I was gonna get as much money as I could. My first payroll with Indian was $57. I never forgot that. Now, if you put all those winnings together, you wouldn't have too much. Harley was a nice outfit to work for. Anything we wanted, they would make for us. I wanted a pair of little narrow handle bars for board tracks to get me closer to the tank, because you just lean on a board track, you don’t steer at all. They made ’em up for me right away.

“The first Dodge City race I got in on was in 1920. I tell you, they were still ridin’ horses and carryin’ guns. And they had what they called Boot Hill, almost at the entrance to the speedway. Years later, they moved Boot Hill downtown. The track itself, in recent years I’ve flown over it several times, and you know, you can still see the outline of that track in the wheat fields. It was banked on the turns and a mile long, all dirt. I don’t think we had over 30 riders in a 300miler, I know Harley started seven machines, and all seven of ’em finished the race, which was pretty good. I think we turned close to 85, 90 miles per hour, something like that, for 300 miles, and I know on our lap charts, our last lap was just as fast as the first one.

“In those days they didn’t have chloride or anything like that, and ridin’ on those dirt tracks was dusty. If you were out in front, you were in pretty good shape, but the fellows that were behind you, they couldn’t see anything. Chloride was salt, is actually what it was, it laid the dust down. The dust would raise maybe a couple of feet, then settle back down. They started using it way back in the 20s, but at some tracks they’d sprinkle light oil out to keep the dust down.”

Davis's career prospered, but towards the end of the 1930s, change was in the air. The end of Class A racing, with its purpose-built racebikes, was near, to be replaced with Class C racing, which called for race-prepped production bikes. This change was to spell the end of Davis's racing career.

"I STAYED WITH HARLEY QUITE a number of years, and I think in `26 I left Harley and went back with In dian. I got a little more money. I rode Harley at Altoona in a 100-mile race, and I beat the Indians with my Har ley. Then I left Harley Davidson, went to the factory Indian for `27, and damn, I beat the Harleys that I'd beat the Indians with the year before. I rode Indian then on for, oh, four years or more, then I went back to Harley. That was the end of Class A racing and Indian was not going to race anymore, this would be, I think, ’38 or’39.

“We’d built two race machines to bring to Syracuse, and got ’em all about ready to ship, and Sales Manager Jim Wright—the sales department ran the racing team—came upstairs and said we were not gonna go. Later, I thought I’d go anyway, so I hung those two racing machines on a car and went to Syracuse. When we got to Syracuse, Mr. Wright was sittin’ there, and we didn’t dare let him see the race machines, so I didn’t have nothing to ride. Harley-Davidson was there, Hank Syvertscn was in charge of’em, ’course I’d been riding Harley for a long time. I said, ‘How ’bout loaning me one of these race machines so I can ride?’ I rode it two laps and came in and made some changes on it. And when the afternoon was over, I won four nationals, see, on this borrowed machine. And when I stepped off of it, I said, that’s it, that’s the end of my racing career.

“That’s a long career, I never hurt myself too bad, so that was the end of the line, as far as I was concerned. I liked to win, I rode hard to win. Only way to win is to make up your mind that’s what you want to do. I never knew what second-place money was, because I wasn’t interested in it. And I won my share. In ’22 or ’23, I don’t remember which, they had 17 national championship events and I won all 17 of them. In the overall picture, I had close to 180 medals— 90 gold medals, close to 50 silver and I think about 45 bronze. Probably done 1200, 1500 races in my day, 30,000 miles, at least.

"I knew how fast I could go without taking chances and falling off. Once you fall off, you don't get no place'

“I wouldn’t quit if I was back second or third, I’d keep goin’, because you never know what’s gonna happen in front of you. I broke down a lot of times—that was racing—but to me, I lapped up every minute of it. But oh, I wouldn’t take anything in the world for the experience I got.”®

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontConversations

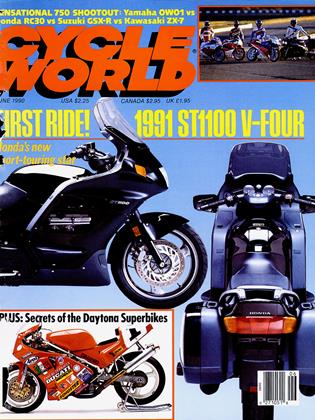

June 1990 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeThe Sport of the '90s

June 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsLegal Tender

June 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupBrm Spyder Upgrading the Gsx-R1 100's Flash Factor

June 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

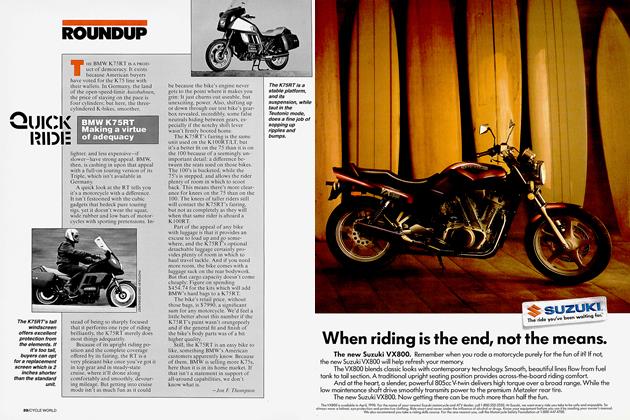

RoundupBmw K75rt Making A Virtue of Adequacy

June 1990 By Jon F. Thompson