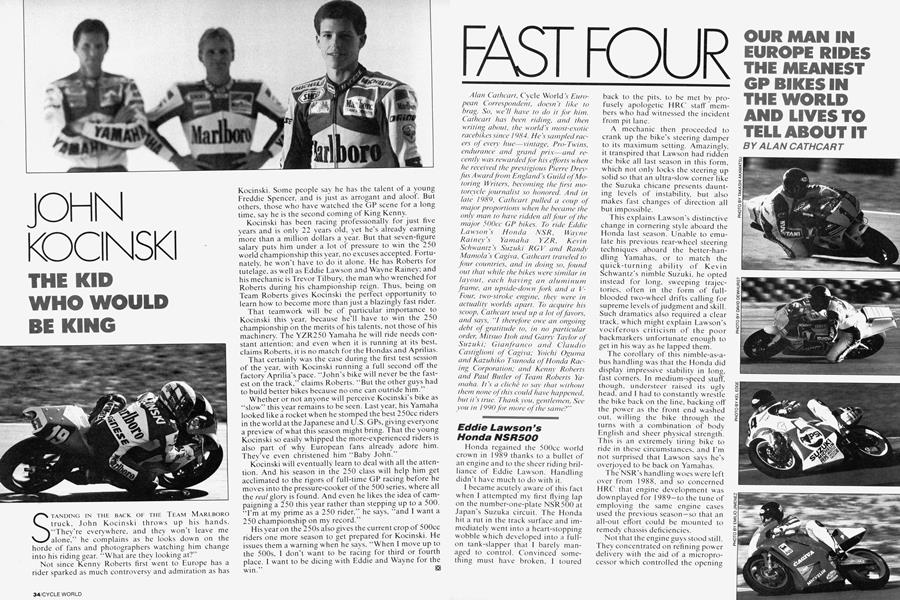

FAST FOUR

OUR MAN IN EUROPE RIDES THE MEANEST GP BIKES IN THE WORLD AND LIVES TO TELL ABOUT IT

ALAN CATHCART

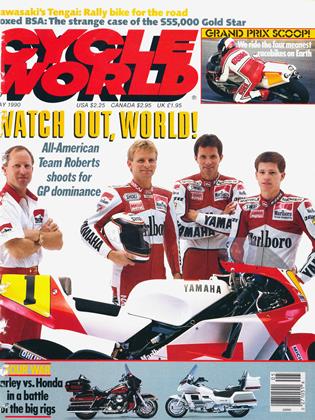

Alan Cathcart, Cycle World’s European Correspondent, doesn't like to brag. So, we II have to do it for him. Cathcart has been riding, and then writing about, the world's most-exotic racebikes since 1984. He's sampled racers of every hue—vintage, Pro-Twins, endurance and grand prix—and recently was rewardedfor his efforts when he received the prestigious Pierre Dreyfus Award from England's Guild of Motoring Writers, becoming the first motorcycle journalist so honored. And in late 1989, Cathcart pulled a coup of major proportions when he became the only man to have ridden all four of the major 500cc GP bikes. To ride Eddie Lawson's Honda NSR, Wayne Rainey's Yamaha YZR, Kevin Sch wantz's Suzuki RGV and Randy Mamola's Cagiva, Cathcart traveled to four countries, and in doing so, found out that while the bikes were similar in layout, each having an aluminum frame, an upside-down fork and a VEour, two-stroke engine, they were in actuality worlds apart. To acquire his scoop. Cathcart used up a lot of favors, and says, “I therefore owe an ongoing debt of gratitude to, in no particular order, Mitsuo ltoll and Garry Taylor of Suzuki; Gianfranco and Claudio Castiglioni of Cagiva; Yoichi Oguma and Kazuhiko Tsunoda of Honda Racing Corporation; and Kenny Roberts and Paul Butler of Team Roberts Yamaha. It's a cliché to say that without them none of this could have happened, but it's true. 7hank you, gentlemen. See you in 1990for more of the same?"

Eddie Lawson's Honda NSR500

Honda regained the 500cc world crown in 1989 thanks to a bullet of an engine and to the sheer riding brilliance of Eddie Lawson. Handling didn't have much to do with it.

I became acutely aware of this fact when I attempted my first flying lap on the number-one-plate NSR500 at Japan's Suzuka circuit. The Honda hit a rut in the track surface and immediately went into a heart-stopping wobble which developed into a fullon tank-slapper that I barely managed to control. Convinced something must have broken. I toured back to the pits, to be met by profusely apologetic HRC staff members who had witnessed the incident from pit lane.

A mechanic then proceeded to crank up the bike's steering damper to its maximum setting. Amazingly, it transpired that Lawson had ridden the bike all last season in this form, which not only locks the steering up solid so that an ultra-slow corner like the Suzuka chicane presents daunting levels of instability, but also makes fast changes of direction all but impossible.

Th is explains Lawson’s distinctive change in cornering style aboard the Honda last season. Unable to emulate his previous rear-wheel steering techniques aboard the better-handling Yamahas, or to match the quick-turning ability of Kevin Schwantz's nimble Suzuki, he opted instead for long, sweeping trajectories, often in the form of fullblooded two-wheel drifts calling for supreme levels of judgment and skill. Such dramatics also required a clear track, which might explain Lawson's vociferous criticism of the poor backmarkers unfortunate enough to get in his way as he lapped them".

The corollary of this nimble-as-abus handling was that the Honda did display impressive stability in long, fast corners. In medium-speed stuff, though, understeer raised its ugly head, and I had to constantly wrestle the bike back on the line, backing off the power as the front end washed out, willing the bike through the turns with a combination of body English and sheer physical strength.

T his is an extremely tiring bike to ride in these circumstances, and I'm not surprised that Lawson says he’s overjoyed to be back on Yamahas.

I he NSR's handling woes were left over from 1988, and so concerned HRC that engine development was downplayed for 1 989-to the tune of employing the same engine cases used the previous season—so that an all-out effort could be mounted to remedy chassis deficiencies.

Not that the engine guys stood still. They concentrated on refining power delivery with the aid of a microprocessor which controlled the opening rate of the engine's powervalves, working off not only rpm but also the degree of opening of the throttle. Four different computer chips altered the ratio in which the two factors were combined, while a muchwider choice of chips varied the curve of the computerized ignition system. This meant that the Honda boasted a true engine-management system of the type more usually associated with race cars.

HRC engineers also managed to extract more horsepower from the NSR engine for 1989, coyly quoting “over 160 horsepower" at 12.000 rpm. This figure is now the benchmark for GP power, and if you haven't got at least that much, you're not in the hunt. Taming these massive outputs by widening the spread of power and softening the delivery, as well as uprating the chassis to cope with it. is now' the name of the game, and a difficult one at that, as my ride aboard Lawson’s Honda showed.

Leaving the pits on the way to my run-in with the vicious tank-slapper,

1 was amazed by the ease with which the NSR trickled off from rest w ith a minimum of revs and almost no clutch slip, just like a mega-fast roadbike. It started to carbúrate well from as low as 7300 rpm. but came on the pipes very strongly at just over 8000 revs with a massive mid-range delivery that seemed strong enough to pull the side off Mt. Fuji. 1 he bike just rocketed forward in a way Fd never experienced on any other racebike—including the other three GP bikes ridden for this story—the power building very fast until it reached its peak at 12.000 rpm. But the NSR also offers a very useful 800 rpm “overrev" capacity, enabling a gear to be held between corners before the power drops off abruptly at 12.800 rpm.

Lawson’s fourth world title, and his first (perhaps only?) one on a Honda, was undoubtedly his hardestearned: He realized the limitations of the Honda chassis early on, had the frame beefed up with a sturdy crossbrace above the engine and with an extra layer of metal welded unprettily to the top of the frame spars, and from then on. rode the bike in every race to the maximum of its potential. Capitalizing on the NSR's strong points, and doggedly working around its weak ones, Lawson proved that he's a worthy champion if ever there was one.

Wayne Rainey's Yamaha YZR500

No other current grand prix racing motorcycle has been more patiently or painstakingly evolved than Yamaha's YZR500. Where Honda, Suzuki and especially Cagiva have constructed what are in effect completely new motorcycles for each season, Yamaha has refined its existing design, which has won three world titles Tn the last five years.

The team almost copped a fourth title in 1989. with Wayne Rainey leading the championship chase for most of the season until being overhauled by Lawson in the closing stages. Before this, Rainey had looked an unassailable champion, helped not only by the phenomenal reliability of the team Roberts Yamaha, but also by the team's eagerness to avail itself of every possible technological advantage.

Thus, Team Roberts debuted the first computerized data-acquisition system to be seen in the 500cc GP class, an on-board telemetry setup, developed in conjunction with Britain's Cranfield Institute of Technology. that could be programmed to monitor almost any aspect of the motorcycle's behavior, from suspension travel to power curve, from chassis flex to airbox pressure. It took the team a few races to figure out how to analyze this sudden wealth of information. but once they did. it was put to effective use in improving certain areas which had remained trouble spots on the YZR design —throttle response, for example.

Riding the Yamaha for my firstever laps at Laguna Seca Raceway was an interesting exercise. A fireeating, 500cc GP racer is hardly the ideal tool with which to learn such a sinuous track, but the YZR was so flexible and forgiving it could be ridden on and off' the throttle, in and out of the powerband, with impunity. The Yamaha’s responsiveness was truly impressive at all revs, carburating as low as 6500 rpm. transitioning cleanly into strong power at around 8000 revs and buildins strongly but not uncontrollably up to maximum power at 12.000 rpm, with an overrev to 12.600, though Roberts said that with a different combination of pipes and ignition chip, it would rev to more than 1 3,000, at the cost of some low-down tractability.

Unlike riding the Honda NSR. there wasn't the feeling that the bike was running away, out of control. Sure, the Yamaha had blisteringly quick acceleration, but 1 had the sense (illusion, maybe?) of being more or less in command. For a race engine, the YZR's V-Four really was a pussycat, albeit a breed of feline with more than 160 horsepower under its claws.

Over Laguna's occasional bumps and ripples, the behavior of the Öhlins suspension fitted front and rear was exemplary. Running over the ridge w here the new infieldsection meets the old track, cranked over to the left and with power on hard to get a good drive up the hill that follows, provided graphic illustration of the suspension's responsiveness. 1 he YZR took the bump as if floating on air. a tribute to long hours of experimentation fueled by feedback from the computer. There was no chatter, no hop, skip or jump, just . . .suspension. The way it should be.

While thé Yamaha's twin-spar frame was very similar to previous units, some alterations w ere made for 1989. including the fitting of a threequarter-inch shorter swingarm to improve traction by throwing more weight onto the rear wheel. The benefit was notably better drive out of turns than that of previous Yamahas I've sampled, though it had picked up a certain reluctance to flick from side to side. The YZR also exhibited understeer in turns, though not as vividly as the rival Honda. The Yamaha did require a certain physical commitment on the part of the rider, too: You couldn't just sit in the saddle and ride 'em cowboy, but a firm hand was amply rewarded, whereas with the Honda, it was barely tolerated.

The Team Roberts Yamaha epitomizes grand prix racing’s endless search for perfection: an" ultimately frustrating one, because there’s always something to improve. But if any team should ever achieve the nirvana of GP motorcycle development, it'll be learn Roberts, and with Eddie Lawson joining Wayne Rainey on the squad for this season, the odds must be very short that King Kenny will finally achieve his first world title as a team owner.

Kevin Schwantz’s Suzuki RGV500

I hough the 1989 championship may have gone to Eddie Lawson and Honda, there wasn't much doubt as to which was the dominant combination in 5()0cc GP racing last year: Kevin Schwantz and the Pepsi Suzuki XR74 RGV500.

“Revvin' Kevin won six races in total (twice as many as Lawson or Rainey), was leading two more when he crashed, and suffered mechanical retirement in three others while either well placed or seemingly certain to win. Without those DNFs he'd most assuredly been crowned champion. And even though racing is about achievement, not conjecture, fourth place at the end of the season seemed a poor reward for the combined brilliance of the lanky Texan and his high-flyin’ Suzuki.

This somewhat unexpected dominance on the machine front came after Suzuki completely redesigned its 3-year-old motorcycle. The bike went on a major slimming exercise to reduce weight as well as bulk. The result was that the heaviest Japanese works bike in '88, at more than 286 pounds, was the lightest in '89, at just over 264.

At the same time, the engine was revamped internally so that the twin crankshafts would counter-rotate like the Yamaha and Cagiva powerplants. This has so many benefits— reduced weight thanks to elimination of the intermediate gear, reduced vibration and reduced gyroscopic effect—it's a wonder it wasn't done sooner.

This was the first time I'd ridden the new-generation Suzuki, as I'd been kept off the '88 model XR73 because its powerband was considered to be so sudden and razor-thin that it was unsuitable for entrusting to the hands of a mere journalist. The '89 model I rode at England's Snetterton racetrack was 180 degrees in the opposite direction: While the engine had an almost-uncontrollable appetite for revs, it pulled from almost as low as an RC30 Honda motor and was nearly as tractable as a BMW Boxer. This was achieved with new cylinders and pipes, a revised powervalve system and a wider range of chips for the ignition system — though with no Team Roberts-type on-board computer, the team tended to stick to three or four chips they knew best.

Even with its easily modulated powerplant. the RGV proved to be a very, very fast bike, sending its front wheel pawing at the sky when I cracked open the throttle in almost any gear, indicating some radical chassis geometry as well as massive reserves of race-winning horsepower.

What this meant in riding terms is that I had to ride the Suzuki more like a four-stroke than a GP racer, using one gear higher than I would nor" mally, and letting the superb torque of the gutsy engine pull me out of turns, at which point. I'd scream the motor before hitting the next-higher gear. In fact, the Suzuki was more tractable than many Superbikes I've ridden, pulling cleanly away from rest without slipping the clutch. The engine came on strong at 7500 rpm, yet would overrev beyond the peak power mark at 1 3,000 revs to I 3,700 with only a slight drop in power. Within that rev range, there was no step in the powerband, only liquidsmooth delivery that, while not as intense as the Honda's mid-range, certainly felt more usable.

By common consent the RGV Suzuki was 1989’s best-handling 500 GP bike, to which I'd add, only if you can adjust to its quirky manners, tailored to Schwantz’s exuberant, almost-MX-style of riding. In designing the bike, Suzuki moved the engine further back and higher up compared to current conventional wisdom, which improved traction and sped up cornering by maximizing weight transfer front to rear and side to side. However, as I found out, it also meant that its riders needed fast reactions to catch the bike as it fell into turns. Pulling the Suzuki upright on the way out was a physically demanding act. until I learned to gas it at the apex and. as the front wheel reached for the sky. complete the turn by means of “body Texan.” This obviously is a highly specialized, acquired art and explains the unusual ergonomics favored by Schwantz: High-set. wide bars giving an upright riding position more like a Superbike than a GP racer.

But it does mean that the Suzuki is noticeably more nimble and tightturning than any of the other bikes except perhaps the Cagiva. which however has traction problemson the exit that the Suzy doesn't.

So. welcome back to the winner's circle, Suzuki. After two world 500cc crowns in succession at the start of the 1980s with the rot ary-valve. square-Four RGB. Suzuki had been out of contention for too long. Now, it s back, with the fastest, if not mostconsistent. rider in GP racing at the helm of an improved RGV500 for I 990. Who’s to say that Suzuki won’t start the new decade just as it did the old one by regaining the prized 500cc world title?

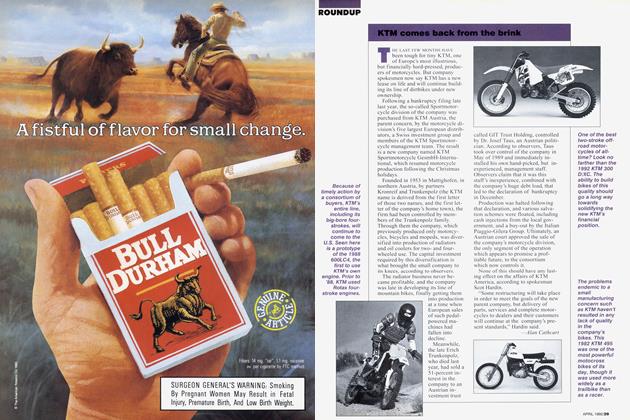

Randy Mamola’s Cagiva V589

If world titles were awarded on the basis of enthusiasm and dedication to a cause, the Italian Cagiva team would by now have been crowned champions several times over. The Quixotic campaign bv the hvperkeen Castiglioni brothers to tweak the noses of the Japanese giants by winning a 500cc GP or two attained its 10th birthday in 1989. but. ironically, the team ended up farther from its goal.

Rider Randy Mamola seemed more interested in entertaining the crowds than in actually going racing, though after a wheelie went horribly wrong cm the warm-up lap at Assen, he seemed to get serious at last and put in some reasonable rides in the second half of the year. But taking the season as a whole, the Cagiva’s results were a long way off those of just two years ago. when then-riders Raymond Roche and Didier de Radigues were regularly finishing in the top five, and a serious Furopean challenge to established Japanese supremacy seemed to have been born Sadly, 1989 showed that not to be the case, though as usual there was an identifiable reason, or should that be excuse? Yet again. Cagiva produced an all-new motorcycle for the season, and then proceeded to spend the whole of the first part of the year developing the bike. 1 his put them hopelessly behind the eight ball vis-avis the Japanese teams, which Mamola’s lack of serious commitment only underlined.

Yet on paper the V589 Cagiva had all that it takes to be competitive. Though still a little overweight at 282 pounds, the new bike was smaller and neater than before, with a stiffer chassis of Carpental 720 aircraft alloy (with distinctive scalloped grooves in the twin spars to add rigidity) and shapely new bodywork by master stylist Massimo Tamburini. But the steering geometry is radical in the extreme, with a forward weight distribution of 60/40 percent and a rake of just 2 1.3 degrees.

Not surprisingly, in view of those figures, the Cagiva proved to steer extremely quickly when 1 sampled it at Spain's switchback-laced Jerez circuit. It entered turns more easily than any of its Japanese rivals, especially under braking, and it also moved from side to side with relatively little effort. But there were serious traction problems when power was applied for the drive out, doubtless owing to a combination of that far-forward weight bias and inadequate rear-suspension response. Originally, the bike was designed for a horizontal Öhlins rear shock, to permit improved extraction of hot air from the engine, but this was changed to a vertical location after Mamola complained about the handling. The resultant compromise isn't a success: Basically, the bike feels unbalanced and could surely do with a shorter swingarm to move some of the weight rearwards and improve the drive out of turns. Revising the suspension linkage to offer more travel and progression wouldn’t hurt, either.

There were other problems, too. That steep head angle and minimal trail induced considerable straightline instability, especially under hard acceleration, which could only be cured by screwing the steering damper up tight, in turn subtracting from the chassis’ one strong point, its nimbleness in turns. Basically, the Cagiva was like a Hollywood matron, whose good-looking haute couture clothes conceal a host of flaws.

Like the Yamaha YZR engine which the Cagiva has lately resembled, the V589 featured a wider. 70degree angle between the cylinders to offer more space for the reed boxes and better airflow to the carbs. But the two engines were quite different in character to ride, for the Cagiva was all mid-range, with hardly any top-end and nil overrev capability. Peak power of 153 horsepower (about 10 less than the Japanese) was produced at 12,200 rpm, and that s exactly the mark on the tach at which the engine ran into a brick wall, and it was time to change gears. Since there was little power below 8000 revs and a step in the power delivery at 9200 rpm which would unhook the rear wheel if I wasn't ready for it. the Cagiva was awkward to ride by modern standards. The nature of the power delivery required that I use one or sometimes even two gears higher than I might otherwise do in a corner to take full advantage of the power-packed mid-range and avoid running out of revs at the wrong moment on the exit. This was not an easy or enjoyable motorcycle to ride, nor did it have the top-speed performance of the Japanese trio: Cagiva has some serious work to do if it's to regain the competitiveness it had a couple of seasons ago. Mamola will be joined by Englishman Ron Haslam, arguably the best development rider in the world today, for 1990, and the Castiglioni brothers' dream of GP victory continues.

Conclusions

All right, then. Which one of these four GP rocketbikes was the best? Ask a straight question and you get a straight answer: the Suzuki. Its handling and weight distribution wouldn’t suit every rider, but the incredible performance of the XR74 engine was sufficient to place it ahead of its rivals. No, it didn't have the top-end speed of the Honda and Yamaha, but what counted more was its combination of ultra-wide power spread and smooth delivery, overrev capability, ease of steering and speed of handling.

The Yarnaha was in many ways the best all-rounder, a bike that has been carefully honed over the years so that any bad points it may once have had have been gradually eliminated. A few more revs at the top-end. a bit more nimbleness in the handling—especially on the turn-in—and it would have been a match for the Suzuki. However, one can't help wondering if the YZR design-only mildly revised for 1990—has not reached the end of its evolutionary cycle. Is a redesign necessary, Suzuki-style, to make it a title-winner again?

In spite of being the world-championship winner, the Honda relied too strongly on its massive engine output tobeconsidered the best bike. Itschassis deficiencies seem to be a perennial Honda problem that won't go away. However, there is hope, because 1990 will see GP racing’s numberone chassis wizard, Antonio Cobas, working on an NSR500 tor the first time as Sito Pons returns to the 500cc class, and in view ol his achievements in other categories, if anyone can resolve the Honda’s handling problems, Cobas can. Whether that information will be shared with other Honda riders is another matter.

And finally, what of Cagiva? Well, the Italian stallion remains the only European bike in 500cc GP racing, and with the new three-man team of Haslam, Mamola and teenage Brazilian hotshot Alexandre Barros, perhaps 1990 will finally see the longawaited breakthrough for the Castiglioni's race team, to match the achievements of their Ducati cousins in Superbike racing. But the bike needs to be completely revamped, especially in the engine department so as to emulate the Suzuki (and Yamaha) trick of achieving more horsepower while at the same time broadening the spread of power. The Cagiva chassis steers as well or even better than any of its rivals at present, but only at the expense of so many other drawbacks that the overall result is seriously flawed.

As a new' decade dawns, the face of 500cc GP racing is changing, with fuel injection on the horizon, a different weight limit introduced for 1990 giving twin-cylinder bikes a 44pound weight advantage, and the Norton rotary accepted in principle for GP racing on a 1:1 swept-volume basis. My chance to compare the four works machines which contested in 1989 represents a freeze-frame image of a page in GP history which is even now turning: A decade trom now, the picture w ill be very different.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue