THE MAKING OF A CHAMPION

A dirt-tracker hits the road

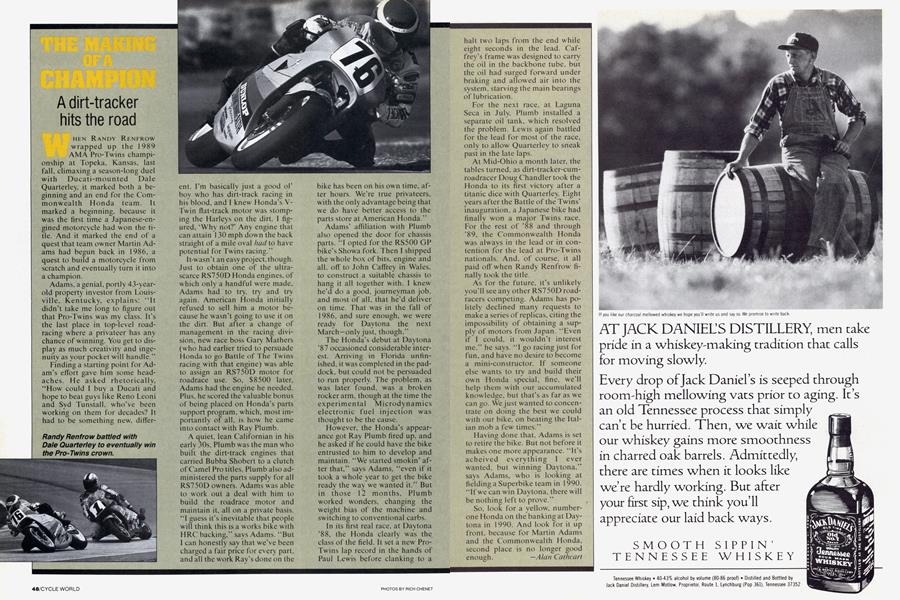

WHEN RANDY RENFROW wrapped up the 1989 AMA Pro-Twins championship at Topeka, Kansas, last fall, climaxing a season-long duel with Ducati-mounted Dale Quarterley, it marked both a beginning and an end for the Commonwealth Honda team. It marked a beginning, because it was the first time a Japanese-engined motorcycle had won the title. And it marked the end of a quest that team owner Martin Adams had begun back in 1986, a quest to build a motorcycle from scratch and eventually turn it into a champion.

Adams, a genial, portly 43-year-old property investor from Louis-ville, Kentucky, explains: “It didn’t take me long to figure out that Pro-Twins was my class. It's the last place in top-level road-racing where a privateer has any chance of w inning. You get to display as much creativity and ingenuity as your pocket will handle.” Finding a starting point for Adam’s effort gave him some headaches. He asked rhetorically, “How could I buy a Ducati and hope to beat guys like Reno Leoni and Syd Tunstall, who’ve been working on them for decades? It had to be something new. different. I'm basically just a good of boy who has dirt-track racing in his blood, and I knew' Honda's V-Twin flat-track motor was stomping the Harleys on the dirt. I figured, ‘Why not?’ Any engine that can attain 130 mph down the back straight of a mile oval had to have potential for Tw ins racing.”

It-wasn’t an easy project, though. Just to obtain one of the ultrascarce RS750D Honda engines, of w hich only a handful were made, Adams had to try, try and try again. American Honda initially refused to sell him a motor because he wasn’t going to use it on the dirt. But after a change of management in the racing division, new race boss Gary Mathers (who had earlier tried to persuade Honda to go Battle of The tw ins racing with that engine) was able to assign an RS750D motor for roadrace use. So, $8500 later, Adams had the engine he needed. Plus, he scored the valuable bonus of being placed on Honda's parts support program, which, most importantly of all, is how he came into contact with Ray Plumb.

A quiet, lean Californian in his early 30s. Plumb w'as the man who built the dirt-track engines that carried Bubba Shobert to a clutch of Camel Pro titles. Plumb also administered the parts supply for all RS750D owners. Adams was able to work out a deal with him to build the roadrace motor and maintain it, all on a private basis. ‘T guess it’s inevitable that people w'ill think this is a works bike with HRC backing,” says Adams. “But 1 can honestly sav that we’ve been charged a fair price for every part, and all the w'ork Ray’s done on the bike has been on his ow n time, after hours. We’re true privateers, with the only advantage being that we do have better access to the parts store at American Honda.”

Adams' affiliation with Plumb also opened the door for chassis parts. “I opted for the RS500 GP bike’s Showa fork. Then I shipped the whole box of bits, engine and all. off to John Caffrey in Wales, to construct a suitable chassis to hang it all together with. I knew he'd do a good, journeyman job. and most of all, that he’d deliver on time. That w'as in the fall of 1986. and sure enough, we were ready for Daytona the next March—only just, though.”

The Honda’s debut at Daytona ’87 occasioned considerable interest. Arriving in Florida unfinished, it was completed in the paddock. but could not be persuaded to run properly. The problem, as was later found, w'as a broken rocker arm, though at the time the experimental Microdynamics electronic fuel injection was thought to be the cause.

However, the Honda’s appearance got Ray Plumb fired up. and he asked if he could have the bike entrusted to him to develop and maintain. “We started smokin’ after that,” says Adams, “even if it took a whole year to get the bike ready the way we wanted it.” But in those 12 months. Plumb worked wonders, changing the weight bias of the machine and switching to conventional carbs.

In its first real race, at Daytona ’88, the Honda clearly w-as the class of the field. It set a new ProTwins lap record in the hands of Paul Lew'is before clanking to a halt two laps from the end while eight seconds in the lead. Caffrey’s frame was designed to carry the oil in the backbone tube, but the oil had surged forward under braking and allowed air into the system, starving the main bearings of lubrication.

For the next race, at Laguna Seca in July, Plumb installed a separate oil tank, which resolved the problem. Lewis again battled for the lead for most of the race, only to allow Quarterley to sneak past in the late laps.

At Mid-Ohio a month later, the tables turned, as dirt-tracker-cumroadracer Doug Chandler took the Honda to its first victory after a titanic dice with Quarterley. Eight years after the Battle of the Twins' inauguration, a Japanese bike had finally won a major Twins race. For the rest of ’88 and through '89, the Commonwealth Honda was always in the lead or in contention for the lead at Pro-Twins nationals. And, of course, it all paid off when Randy Renfrow finally took the title.

As for the future, it’s unlikely you’ll see any other RS750D roadracers competing. Adams has politely declined many requests to make a series of replicas, citing the impossibility of obtaining a supply of motors from Japan. “Even if 1 could, it wouldn't interest me.” he says. “I go racing just for fun, and have no desire to become a mini-constructor. If someone else wants to try and build their own Honda special, fine, we'll help them with our accumulated know ledge, but that’s as far as we can go. We just wanted to concentrate on doing the best we could with our bike, on beating the Italian mob a few' times.”

Having done that, Adams is set to retire the bike. But not before it makes one more appearance. “It’s acheived everything I ever wanted, but winning Daytona.” says Adams, who is looking at fielding a Superbike team in 1990. “If we can wán Daytona, there will be nothing left to prove.”

So, look for a yellow, numberone Honda on the banking at Daytona in 1990. And look for it up front, because for Martin Adams and the Commonwealth Honda, second place is no longer good enough.

Alan Cathcart

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

February 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

February 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

February 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1990 -

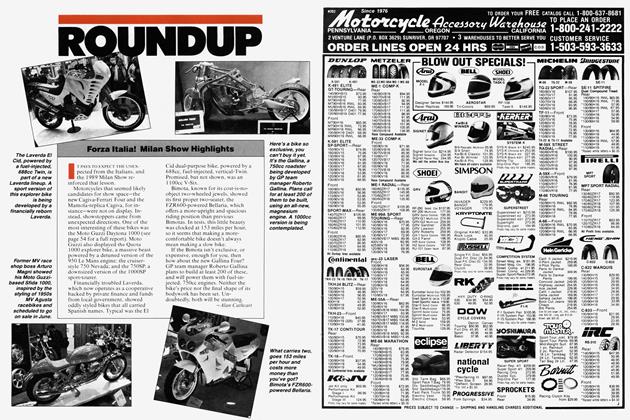

Roundup

RoundupForza Italia! Milan Show Highlights

February 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

Roundup1990 Ducatis, Husqvarnas: Don't Call 'em Cagivas Anymore

February 1990