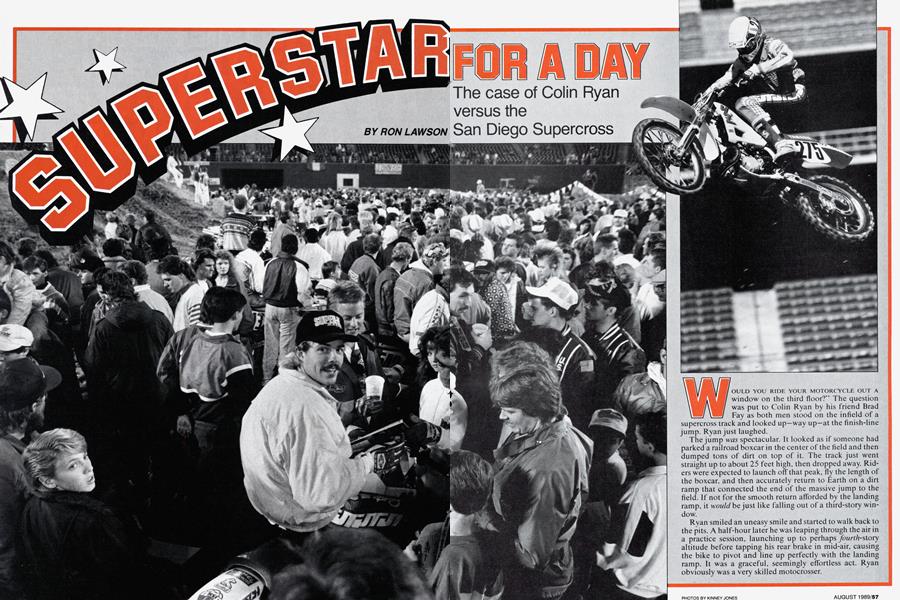

SUPERSTAR FOR A DAY

RON LAWSON

The case of Colin Ryan versus the San Diego Supercross

WOULD YOU RIDE YOUR MOTORCYCLE OUT A window on the third floor?" The question was put to Colin Ryan by his friend Brad Fay as both men stood on the infield of a supercross track and looked up—way up—at the finish-line jump. Ryan just laughed.

The jump was spectacular. It looked as if someone had parked a railroad boxcar in the center of the field and then dumped tons of dirt on top of it. The track just went straight up to about 25 feet high, then dropped away. Riders were expected to launch off that peak, fly the length of the boxcar, and then accurately return to Earth on a dirt ramp that connected the end of the massive jump to the field. If not for the smooth return afforded by the landing ramp, it would be just like falling out of a third-story window.

Ryan smiled an uneasy smile and started to walk back to the pits. A half-hour later he was leaping through the air in a practice session, launching up to perhaps fourth-story altitude before tapping his rear brake in mid-air, causing the bike to pivot and line up perfectly with the landing ramp. It was a graceful, seemingly effortless act. Ryan obviously was a very skilled motocrosser.

But skill only counts for so much, and very soon Ryan was going to be in way over his head. And he knew it.

You see, Ryan was a long way from his hometown of Yucaipa, California. Back there, everyone knows him, and everyone knows he’s just about the best rider in town. But this wasn't Yucaipa—this wasn’t like any place he had ever been before. This was San Diego’s Jack Murphy Stadium, and today Colin Ryan would be riding against the best motocrossers in the world. Team Honda’s Rick Johnson was there, so was Kawasaki’s Ron Lechien and Yamaha’s Micky Dymond; in fact, everybody who was anybody in supercross was there. This was Ryan’s first professional supercross. Realistically, he wasn’t there to win, place, or even make the final. His biggest concern was just to prove that he was good enough to belong there; that he could do it.

Like many riders across the country, Ryan has a lot of talent, but not much opportunity. For this one-shot deal, though, he had assembled the sponsors {Cycle World, JT and Race Tech) and the nerve to turn a dream into reality. His hometown friend Brad Fay came out, half to act as a mechanic and half to offer moral support. Ryan would need both. It was hard enough just convincing AMA officials that he could make the cut. Now he had to convince himself.

In practice, Ryan slowly worked on the various obstacles and jumps. Supercross racing has evolved in the 17 years since its inception from an indoor imitation of natural terrain motocross to a spectacular series of jumps linked by tight turns and washboard-like “stutter” sections. As such, there isn't much room for error, and mistakes can easily be career-ending. Ryan practiced accordingly: He would pull over and watch riders as they tried different lines and attempted to clear double-jumps. Doing a double-jump for the first time is like stepping out of a plane without looking to see whether that thing on your back is a parachute or a knapsack. Just because Rick Johnson made it to the other side doesn't mean you will. It’s a battle between the desire to achieve and the desire to survive. The balance between those two instincts is what separates the double-jumpers from everyone else.

During that practice session, the battle raged inside Ryan. There were seven double-jumps on the track, and Ryan was mastering them one by one. More experienced riders flew by, treating practice like a race in itself, but Ryan would stop and look, turn and watch. Most of the battle was focused on one particular double-jump that he had already figured out. The problem was that several riders had turned it into a m'/?/c-jump: They had hit the first jump so hard that they not only cleared the second one, but a third, too. Ryan watched and considered. Before he came to a conclusion, practice was over.

“That's a long way,” he said later, shaking his head. There was no trace of the humor he had shown earlier when he was estimating the height of the finish jump. “The finish-line jump is just big-there's nothing to it. But this thing has no run up to it; it has all these ruts and you have to fly a long way.” If you had strapped Ryan to a torture rack at that point, and if the Grand Inquisitor himself had waved a red-hot branding iron and asked whether or not he was going to do The Triple. Ryan couldn't have answered. He honestly didn’t know. And he wouldn’t know until the very instant came when he had to make the decision to hit the "brakes or the gas. So he sat by his van in a dark corner of the pits and waited for his heat race to come.

The stadium began to fill up. Being in a supercross is a cross between being a racer and being a circus act. The riders come expecting a race; the spectators come expecting a show. Sometimes both happen, sometimes neither happens. At the supercrosses, like San Diego, that Mickey Thompson Entertainment Group puts on, the circus act is heavily emphasized. The riders are poised on the field before the race like gladiators, and the spectators are allowed to swarm around them, to get one good look at the men who would soon be lion food. Ryan was told to report to the infield with the others, so he parked his bike on the field, still thinking about The Triple, and he prepared to get trampled by fans on their way to get Rick Johnson’s autograph.

That didn’t happen. As the infield filled with the spectators, young kids, middle-aged ladies and old men all gathered around Ryan, asking questions and holding out notepads. “They really wanted my autograph,” Ryan said, amazed. “They didn’t know who I was, they just wanted my name on a piece of paper. 1 felt like I was short-changing them.”

Colin Ryan, for the first time in his life, was a hero. He liked it. The autograph session lasted about an hour, and when it was all over, Ryan’s attitude was improved. Double-jumps? No problem. Triple-jumps? Cake. It was time to go racing.

Ryan’s qualifying heat had Rick Johnson, Micky Dymond and a handful of other stars lined up and waiting for the gate to drop. When it did, Johnson jumped into the lead and Ryan jumped into last place. But in the first turn, there was chaos.

“Dymond hit somebody and started to fall into me. I just had to gas it to get by him before he hit the ground in front of me,” said Ryan. With bikes dodging and swerving in every direction, Ryan exited the first turn in sixth place, not that far behind Johnson himself. Ryan had no idea what was happening behind him, he just watched the riders in front. The six of them hit the first set of whoops, then a set of doubles, then a long, rough straight. After that, there was a sharp turn and then The Triple. “I saw those first five riders clear the triple and I knew what I was going to do. I had to do it,” Ryan said.

He came out of that turn harder than he ever had before, and hit the first jump going as fast as he could go: “I was in the air forever. And when I landed, it was so smooth; it was perfect.” Ryan had done The Triple

The race continued, but after that first jump, Ryan had already done what he came to do. In the private battle called Colin Ryan versus The Triple, Ryan won, handsdown, no-contest on the first lap. Other, less-important laps came after that, and sometimes Ryan did the triple well, sometimes he did it poorly and sometimes he didn't do it at all. Didn’t matter. In fact, all the laps in all the races that came after that didn’t matter. Ryan fell short of making the main event by a few places in his heat, his semi and the last-chance qualifier, and even that didn’t matter. All that counted was that moment on the first lap of the heat race when Ryan proved to himself that he belonged there.

When the race was all over, Ryan looked as though the weight of the entire stadium had just been taken off his shoulders. He didn’t have much to say about the race. “I did that jump for me, nobody else,” he said, positively glowing with inner satisfaction. That night, Ryan, Fay and a handful of Yucaipa people from the stands celebrated a win. Oh, Rick Johnson might have thought he won as he took his bows to the crowd. Some people knew better. Whatever emotional high Johnson was going through at that time was just one of many in a career that will be noted in racing history.

But for Colin Ryan, who finished around 33rd that night, who you won’t ever find in any record books, and who Rick Johnson didn’t even notice, it was the win of a lifetime.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

August 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

August 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

August 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupNew, Top-Secret Triumph Revealed

August 1989 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupFor Japan Only: the High-Tech 250s

August 1989 By David Edwards