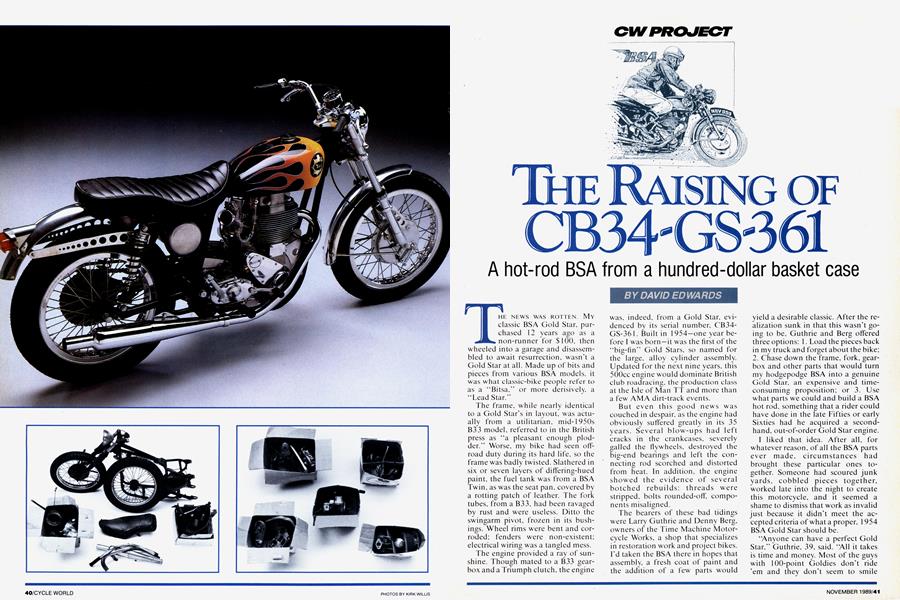

THE RAISING OF CB34-GS-361

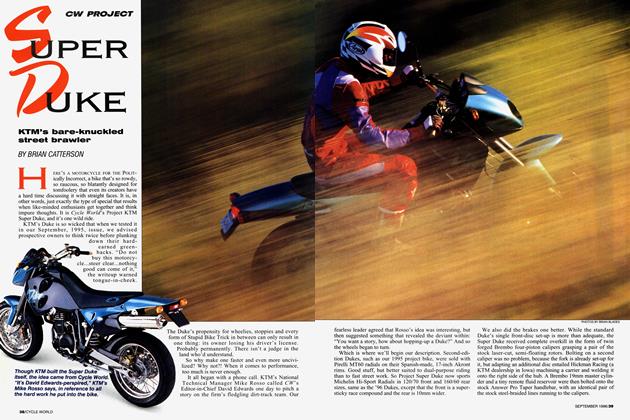

CW PROJECT

A hot-rod BSA from a hundred-dollar basket case

DAVID EDWARDS

THE NEWS WAS ROTTEN. MY classic BSA Gold Star, purchased 12 years ago as a non-runner for $100, then wheeled into a garage and disassembled to await resurrection, wasn't a Gold Star at all. Made up of bits and pieces from various BSA models, it was what classic-bike people refer to as a “Bitsa," or more derisively, a “Lead Star."

The frame, while nearly identical to a Gold Star’s in layout, was actually from a utilitarian, mid-1950s B33 model, referred to in the British press as “a pleasant enough plodder." Worse, my bike had seen offroad duty during its hard life, so the frame was badly twisted. Slathered in six or seven layers of differing-hued paint, the fuel tank was from a BSA Twin, as was the seat pan, covered by a rotting patch of leather. The fork tubes, from a B33, had been ravaged by rust and were useless. Ditto the swingarm pivot, frozen in its bushings. Wheel rims were bent and corroded; fenders were non-existent; electrical wiring was a tangled mess.

The engine provided a ray of sunshine. Though mated to a B33 gearbox and a Triumph clutch, the engine was, indeed, from a Gold Star, evidenced by its serial number, CB34GS-361. Built in 1954—one year before I was born—it was the first of the “big-fin" Gold Stars, so named for the large, alloy cylinder assembly. Updated for the next nine years, this 500cc engine would dominate British club roadracing, the production class at the Isle of Man TT and more than a few AMA dirt-track events.

But even this good news was couched in despair, as the engine had obviously suffered greatly in its 35 years. Several blow-ups had left cracks in the crankcases, severely galled the flywheels, destroyed the big-end bearings and left the connecting rod scorched and distorted from heat. In addition, the engine showed the evidence of several botched rebuilds: threads were stripped, bolts rounded-off, components misaligned.

The bearers of these bad tidings were Larry Guthrie and Denny Berg, owners of the Time Machine Motorcycle Works, a shop that specializes in restoration work and project bikes. I’d taken the BSA there in hopes that assembly, a fresh coat of paint and the addition of a few parts would yield a desirable classic. After the realization sunk in that this wasn’t going to be, Guthrie and Berg offered three options: 1. Load the pieces back in my truck and forget about the bike; 2. Chase down the frame, fork, gearbox and other parts that would turn my hodgepodge BSA into a genuine Gold Star, an expensive and timeconsuming proposition; or 3. Use what parts we could and build a BSA hot rod. something that a rider could have done in the late Fifties or early Sixties had he acquired a secondhand, out-of-order Gold Star engine.

I liked that idea. After all, for whatever reason, of all the BSA parts ever made, circumstances had brought these particular ones together. Someone had scoured junk yards, cobbled pieces together, worked late into the night to create this motorcycle, and it seemed a shame to dismiss that work as invalid just because it didn’t meet the accepted criteria of what a proper, 1954 BSA Gold Star should be.

“Anyone can have a perfect Gold Star," Guthrie, 39, said. “All it takes is time and money. Most of the guys with 100-point Goldies don't ride 'em and they don’t seem to smile much. We can build you a unique bike that’ll make you giggle.”

And so began three months of work that resulted in the bike you see here, a one-öf-a-kind BSA that will soon wear the personalized license plate GDASGLD, for “Good as Gold.”

The first task was to get the five cardboard boxes of engine parts back together. Even though Time Machine has complete engine-rebuilding facilities and had just done a Gold Star engine for another customer, the parts were given to BSA specialist George Lanyon, who raced a rigid-frame Gold Star at Daytona in 1957 and currently owns 19 Gold Stars, including a spotless replica of that racer. Of course, I didn’t help matters by insisting that the BSA’s suspension and carburetion be as up-to date as possible while still remaining true to the hot-rod theme. I knew that oldstyle Italian Ceriani fork assemblies were being made again in response to demands from restorers in England and America, and I wanted one for the BSA. Used on almost every flattracker in the '60s and early ’70s, the Cerianis matched the rest of the bike, even if it did mean that Berg had to fabricate a steering stem and front axle from bar stock in order to mate the assembly to the BSA’s steering head and front hub. While he was at it, Berg installed tapered Timken bearings and made brackets for the chromed Bates headlight and the Smiths Chronometrie speedometer.

Lanyon, 54, had the engine done in a couple of weeks and it looked great. But later, when the engine was bolted into the completed chassis, there would be problems. The rebuilt generator, which Lanyon had jobbed-out, wouldn’t deliver a fat, consistent spark until Berg fiddled with it. Worse, when the engine was started up, it emitted a clatter that didn’t get any better after a valve adjustment and a few break-in miles, necessitating that the top-end be torn down to locate the problem. As this story is being written, Lanyon and Berg are doing just that.

Nor was this the only time that the project ran into problems, as parts ordered from various sources often turned out to be incorrect and wouldn’t work without modification. The moral here is that the process of bringing timeworn bikes back to life, fulfilling though it may be, can be lengthy and frustrating.

At least someone like Berg can make the ordeal bearable. Thirty-five years old, he’s built hundreds of project bikes, everything from choppers to exact restorations, starting with the Honda custom that he and his father built on their farm in South Dakota, welding up their own frame and equipping the bike with lights off a combine. It is Berg, currently building his own hot rod, a rigid-tail Triumph he calls “Brando,” who is responsible for the sparkling, one-off touches on my BSA.

Chief among those are the engine plates, rear-fender brackets and brake-stay arms, all cut from 6061T6 aluminum, then polished and drilled for style and lightness. It was also Berg who suggested and then mounted the aluminum fenders from the British aftermarket firm Wassel, and the spun-aluminum, “Moon” oil tank, looking like it was just relieved of duty as the fuel container on an old-style rail dragster.

The carburetor caused headaches, as well. Because stock Amal carbs tend to wear quickly and can be persnickety about idling, I ordered a new, Italian-made, 34mm “Pumper” Dell’Orto. To match the carb to the cylinder head, though, Berg had to manufacture a manifold, welding a short section of steel tubing to flat stock, then cutting, grinding and filing to fit. At least the modern rear shocks, from Works Performance, mounted up with no tampering.

Topping off Berg’s handiwork and contributing greatly to the BSA's character are the seat and fuel tank. The seat, by Corbin, has a leather, “tuck-and-roll” top section and is roomy enough for two. The fuel tank, done in elongated, “canopener” flames, was painted by Charlie Bussard, father of Cycle World's Executive Editor Camron Bussard and one of the country’s best pin-stripers and muralists.

From its seat and fuel tank right down to the small brackets that Berg built from scratch, there’s a lot to look at on my Gold Star hot rod, a

bike that was literally brought back from the dead through the efforts of some very skilled people. At one point, just before the bike was completed, Berg and I sat in the shop, beers in hand, and talked about qual-

ity and craftsmanship, and about the difficulty he has in turning a machine over to somebody else after putting so much of himself into it.

“Sometimes it is tough to see them go out the door,” he said. “You just hope that people appreciate all the work that goes into building them. I think they do.”

I then asked if he ever considers the work he does to be artistry. Clearly a little uncomfortable with the concept, Berg said that he just thinks of himself as a skilled craftsman who puts together some pretty nice motorcycles.

Still, I think he liked it when I asked him to sign and date the top of my BSA’s oil tank. El

SUPPLIERS Research, planning, parts acquisition, fabrication, final assembly Time Machine Motorcycle Works 755 W.l7th St. #A Costa Mesa, CA 92627 714/548-4424 Price: $5500 Engine building George Lariyon Classic Restorations 396 N. Mountain View Bishop, CA 93514 619/873-6150 Price: $1500 Front fork, triple clamps Storz Performance 1362 Tower Square #2 Ventura, CA 93003 805/654-8816 Price: $750

Shock absorbers Works Performance 8730 Shirley Ave. Northridge, CA 91324 818/701-1014 Price: $240 Wheels Buchanan's 629 E. Garvey Ave. Monterey Park, CA 91754 818/280-4003 Price: $397 Seat Corbin Saddles 11445 Commercial Pkwy. Castroville, CA 95012-0880 800/538-7035 (in California, 800/6626296) Price: $199 FueI.tank painting The Toy Painter 130 High Street

Paris, KY 40361 606/987-1398 Price: $350 Tires J&D Walter Box 340 Old River Rd. Glenmont, NY 12077 8001833-3503 Price: $127 Carburetor Rivera Engineering 6416 S. Western Ave. Whittier, CA 90606 213/692-8944 Price: $75 Clutch plates1 control cables Barneti Tool & Engineering 9920 Freeman Ave. Sante Fe Springs, CA 90670 213/941-1284 Price: $89

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

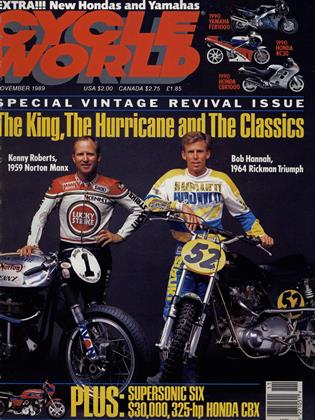

November 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

November 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

November 1989 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsLetters

November 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Update: Spicy News From Across the Sea

November 1989 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha Rings In the New Year

November 1989 By Camron E. Bussard