NESS VISION

RIDING IMPRESSION

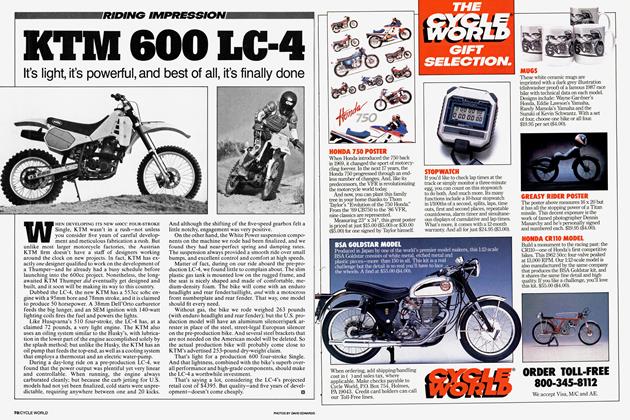

How's it look? Baaaad. How's it sound? Baaaad. How's it work? Not bad at all.

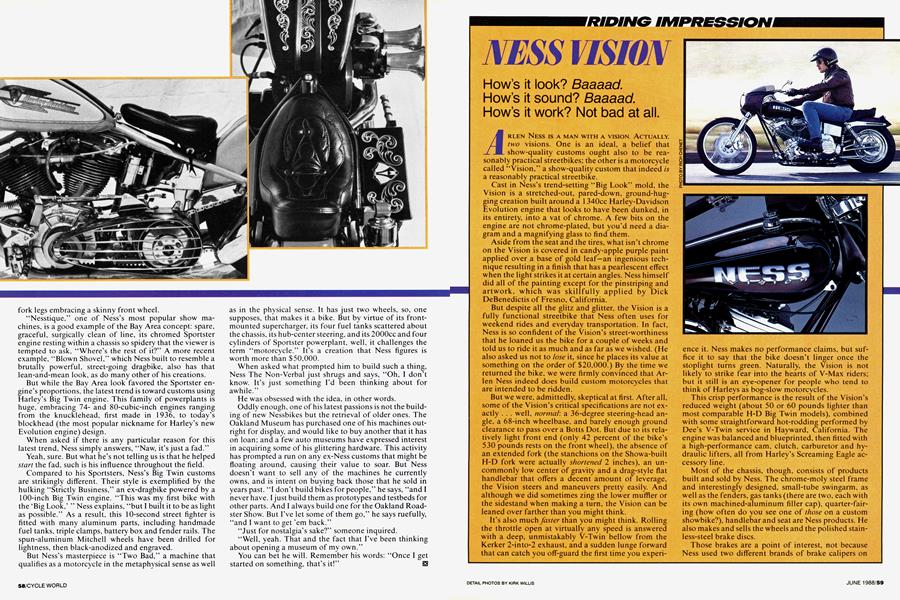

ARLEN NESS IS A MAN WITH A VISION. ACTUALLY, two visions. One is an ideal, a belief that show-quality customs ought also to be reasonably practical streetbikes; the other is a motorcycle called "Vision," a show-quality custom that indeed is a reasonably practical streetbike.

Cast in Ness’s trend-setting “Big Look” mold, the Vision is a stretched-out, pared-down, ground-hugging creation built around a 1340cc Harley-Davidson Evolution engine that looks to have been dunked, in its entirety, into a vat of chrome. A few bits on the engine are not chrome-plated, but you’d need a diagram and a magnifying glass to find them.

Aside from the seat and the tires, what isn’t chrome on the Vision is covered in candy-apple purple paint applied over a base of gold leaf—an ingenious technique resulting in a finish that has a pearlescent effect when the light strikes it at certain angles. Ness himself did all of the painting except for the pinstriping and artwork, which was skillfully applied by Dick DeBenedictis of Fresno, California.

But despite all the glitz and glitter, the Vision is a fully functional streetbike that Ness often uses for weekend rides and everyday transportation. In fact, Ness is so confident of the Vision’s street-worthiness that he loaned us the bike for a couple of weeks and told us to ride it as much and as far as we wished. (He also asked us not to lose it, since he places its value at something on the order of $20,000.) By the time we returned the bike, we were firmly convinced that Arlen Ness indeed does build custom motorcycles that are intended to be ridden.

But we were, admittedly, skeptical at first. After all, some of the Vision’s critical specifications are not exactly . . . well, normal-, a 36-degree steering-head angle, a 68-inch wheelbase, and barely enough ground clearance to pass over a Botts Dot. But due to its relatively light front end (only 42 percent of the bike’s 530 pounds rests on the front wheel), the absence of an extended fork (the stanchions on the Showa-built H-D fork were actually shortened 2 inches), an uncommonly low center of gravity and a drag-style flat handlebar that offers a decent amount of leverage, the Vision steers and maneuvers pretty easily. And although we did sometimes zing the lower muffler or the sidestand when making a turn, the Vision can be leaned over farther than you might think.

It’s also much faster than you might think. Rolling the throttle open at virtually any speed is answered with a deep, unmistakably V-Twin bellow from the Kerker 2-into-2 exhaust, and a sudden lunge forward that can catch you off-guard the first time you experience it. Ness makes no performance claims, but suffice it to say that the bike doesn’t linger once the stoplight turns green. Naturally, the Vision is not likely to strike fear into the hearts of V-Max riders; but it still is an eye-opener for people who tend to think of Harleys as bog-slow motorcycles.

This crisp performance is the result of the Vision’s reduced weight (about 50 or 60 pounds lighter than most comparable H-D Big Twin models), combined with some straightforward hot-rodding performed by Dee’s V-Twin service in Hayward, California. The engine was balanced and blueprinted, then fitted with a high-performance cam, clutch, carburetor and hydraulic lifters, all from Harley’s Screaming Eagle accessory line.

Most of the chassis, though, consists of products built and sold by Ness. The chrome-moly steel frame and interestingly designed, small-tube swingarm, as well as the fenders, gas tanks (there are two, each with its own machined-aluminum filler cap), quarter-fairing (how often do you see one of those on a custom showbike?), handlebar and seat are Ness products. He also makes and sells the wheels and the polished stainless-steel brake discs.

Those brakes are a point of interest, not because Ness used two different brands of brake calipers on the Vision—Performance Machine on the front, Grimeca on the rear—but because he put two separate calipers on the single rear disc, one above the swingarm and one below. “I did it just for fun,” says Ness, “and because I thought it looked kind of neat.” But once again, it’s functional: When you squeeze the Vision’s hand-machined aluminum front-brake lever or mash on its chromed rear-brake pedal, the bike stops.

It also rides half-decently, considering its short rear-wheel travel (about 2 inches) and a seat designed more for style and lowness (just 26 inches off the pavement) than for comfort. But the fat, 15-inch rear tire helps take the edge off most sharp bumps, while the long wheelbase keeps the ride from being too choppy. And the riding position is surprisingly comfortable, thanks to footpegs and handgrips that are rationally positioned.

But that’s not too surprising; “rational” is one of Arlen Ness’s favorite words. And one of his least favorite is “chopper,” the term commonly used to describe custom-style motorcycles with raked-out front ends and apehanger handlebars. “I don’t build choppers,” he says, “because I don’t like to ride them. One of the things I really look forward to when I’m building a new bike is finally being able to ride it when it’s done. If I can’t look forward to riding it, I don’t want to build it.”

Judging by the way the Vision looks, Ness must have had a lot to look forward to while he was building it. Judging by the way it works, he wasn’t disappointed.

Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialDown But Not Out

June 1988 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeMoto-Immortality

June 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsAlas, Albion

June 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1988 -

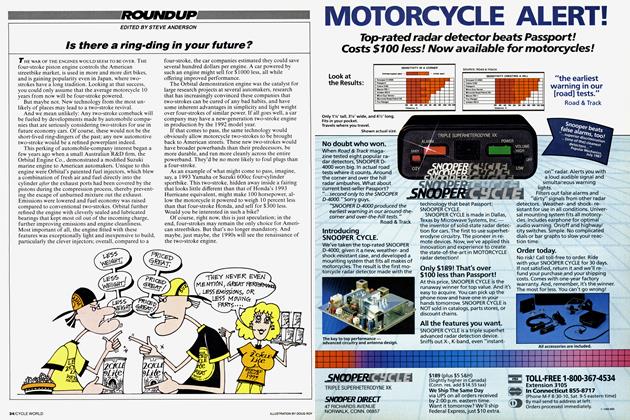

Rondup

RondupIs There A Ring-Ding In Your Future?

June 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Rondup

RondupLetter From Japan

June 1988 By Kengo Yagawa