EDITORIAL

Hometown hotshoes

IN MOTORCYCLING AS WELL AS IN MOST other motor sports, there’s racing, and then there’s racing. The former consists simply of a bunch of riders circulating a track at speed; the latter is what happens when most of the riders in an event engage in knock-down, drag-out, take-no-prisoners dicing for practically every lap of practically every race.

To me, that's racing. And I know where you can find plenty of it.

I’ll bet you think I’m talking about some world-famous events, like the roadraces at Laguna Seca or Loudon, or maybe the legendary dirt-track mile at San Jose or the Superbowl of Motocross in the L.A. Coliseum. But I’m not. The races I’m talking about don’t have familiar names, and they aren’t held just once a year in places so far away from most of you that relatively few of you can go see them. Rather, these are races held on some regular weekly or monthly basis, in places most of you have never heard of, involving riders whose names even fewer of you would recognize. But they’re races that almost all of you can easily go see.

What I’m referring to is local racing, the grass-roots, club-level competition that consists mostly of selfsponsored amateur riders. Like clockwork, they show up at the track every Thursday night or every third weekend or whatever and race their hearts out. And they don’t do it for high stakes; they do it for the thrill of competition and, if they play their cards right, a trophy that’s worth less than their pit pass. In essence, they do it for free.

But that’s why the competition at this level usually is so intense. Amateurs don’t race because they have contracts that say they must or because racing is the way they make their living; amateurs are there because they want to race, pure and simple. And that burning desire to compete motivates them to give it everything they’ve got, every time they’re on the track, all season long.

In professional racing, though, where big money enters the picture in the form of lucrative sponsorships, large purses, contingency payoffs and valuable championships, real racing often suffers, in quantity if not in quality. The sport becomes much more of a haves-versus-have-nots proposition in which the factory riders “have” the most talent and the best equipment. So the only riders with much of a chance of winning are the few who are factory-backed.

What’s more, if most of the factory machines at this highest level of competition aren’t more-or-less deadeven—and they often aren’t—the racing isn’t likely to be close among the few top riders, although the slowest factory riders will still probably outrun the fastest have-nots. But in amateur racing, where riders compete according to skill level, there is a much narrower range of talent and equipment in any given race, which usually results in more head-to-head racing throughout the field.

On top of that, a professional rider is more likely to have his desire to win late-season races overridden by a stronger desire—or that of his sponsor—to win a profitable series title or season championship. When that happens, he plays it safe, riding no harder than necessary to earn the required points. But the quality of racing is diminished as a result.

Factory riders also often show up at a non-points race in which they are contractually bound to ride, but don’t necessarily go out on the track and reall v race. I was reminded of this at the recent Nissan 200 roadrace at Laguna Seca, where winner Mike Baldwin admitted that he had deliberately tried to go as fast as he possibly could on every single lap during the entire weekend. He was criticized by many people for doing that rather than playing the wheelie game that has become a ritual at this annual event (most likely to be won by a rider competing for the world championship, but which earns him no points toward that title). I thought it utterly ludicrous that a race winner was criticized for racing, for wanting desperately to win and doing whatever it took to succeed.

As a race fan, I’m offended by all this non-racing business. I go to a bigtime race to see big-time racing, not show-biz monowheeling or a chessmatch of team strategy and high finance.

Not that the pros aren’t capable of real racing. Some of the best rides I’ve ever seen were by superheroes like Kenny Roberts or Bob Hannah or Jay Springsteen in an end-of-theseason race in which all they had to do is simply finish in the top ten—or sometimes just finish, period—to win a championship. But they didn’t play it safe and “back” into the championship; they rode like men possessed to win not just the title, but the race, as well. Strategy be damned; they were there to race.

That kind of unrestrained racing is found more consistently at a local level than anywhere else. Neither the bikes nor the riders are as fast, of course; but I don’t define “racing” as a world-class pro riding a highly sophisticated machine around a racetrack faster than anyone on the circuit that day. I define it as two or more competitors of any level fighting for any position on any kind of machine. Amateur racing isn’t always the prettiest, either, and you might not find the trickest bikes and the spiffiest riding gear. But you will see desire and determination that is unsurpassed at any level.

So if you’re looking for some real racing, you might not have to wander far from home. It’ll probably be promoted by a club with alphabet-soup initials, at a place where the closest thing to a grandstand is the lawn chair you bring with you, where the “restroom” facilities are anywhere you can find privacy in the tall grass, where the public-address system consists of someone droning unintelligibly through a battery-powered loudspeaker duct-taped to the roof of a dump truck. But with a little luck, you’ll see a collection of local heroes engaged in some of the most intense, most honest racing you’re likely to find. Anywhere.

Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

October 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupBeyond the Ten Best

October 1986 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

October 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

October 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

Features

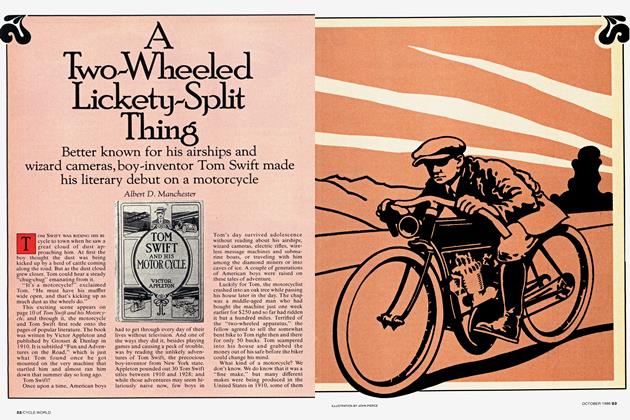

FeaturesA Two-Wheeled Lickety-Split Thing

October 1986 By Albert D. Manchester