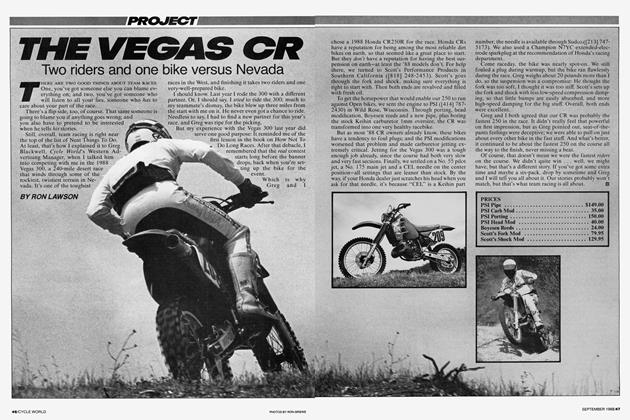

THE CALIFORNIA HUSKY

PROJECT

STARTED IN SWEDEN, FINISHED IN A GARAGE

RON GRIEWE

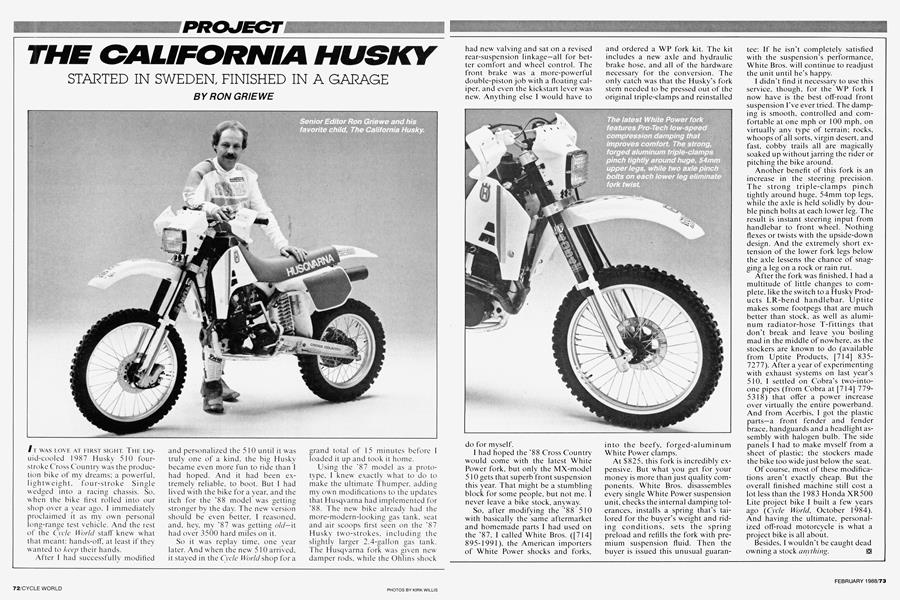

IT WAS LOVE AT FIRST SIGHT. THE LIQuid-cooled 1987 Husky 510 four-stroke Cross Country was the production bike of my dreams; a powerful, lightweight, four-stroke Single wedged into a racing chassis. So, when the bike first rolled into our shop over a year ago, I immediately proclaimed it as my own personal long-range test vehicle. And the rest of the Cycle World staff knew what that meant: hands-off, at least if they wanted to keep their hands.

After I had successfully modified and personalized the 5 10 until it was truly one of a kind, the big Husky became even more fun to ride than I had hoped. And it had been extremely reliable, to boot. But I had lived with the bike for a year, and the itch for the ’88 model was getting stronger by the day. The new version should be even better. I reasoned, and. hey, my ’87 was getting old— it had over 3500 hard miles on it.

So it was replay time, one year later. And when the new 5 10 arrived, it stayed in the Cycle World shop for a grand total of 15 minutes before I loaded it up and took it home.

Using the ’87 model as a prototype, I knew exactly what to do to make the ultimate Thumper, adding my own modifications to the updates that Husqvarna had implemented for ’88. The new bike already had the more-modern-looking gas tank, seat and air scoops first seen on the '87 Husky two-strokes, including the slightly larger 2.4-gallon gas tank. The Husqvarna fork was given new damper rods, while the Ohlins shock

had new valving and sat on a revised rear-suspension linkage—all for better comfort and wheel control. The front brake was a more-powerful double-piston job with a floating caliper, and even the kickstart lever was new. Anything else I would have to do for myself.

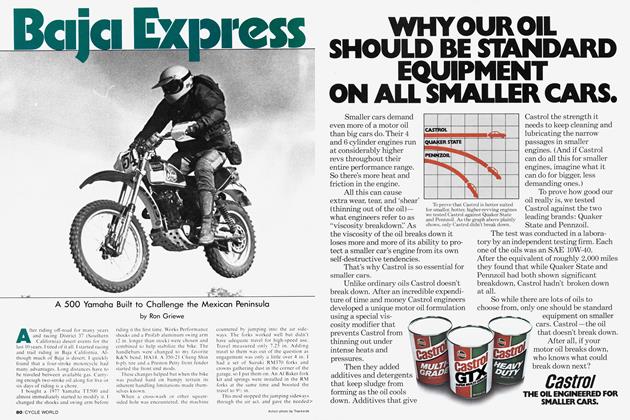

I had hoped the ’88 Cross Country would come with the latest White Power fork, but only the MX-model 5 10 gets that superb front suspension this year. That might be a stumbling block for some people, but not me. I never leave a bike stock, anyway.

So, after modifying the ’88 510 with basically the same aftermarket and homemade parts I had used on the '87, I called White Bros. ([714] 895-1991). the American importers of White Power shocks and forks, and ordered a WP fork kit. The kit includes a new axle and hydraulic brake hose, and all of the hardware necessary for the conversion. The only catch was that the Husky’s fork stem needed to be pressed out of the original triple-clamps and reinstalled

into the beefy, forged-aluminum White Power clamps.

At $825, this fork is incredibly expensive. But what you get for your money is more than just quality components. White Bros, disassembles every single White Power suspension unit, checks the internal damping tolerances, installs a spring that’s tailored for the buyer’s weight and riding conditions, sets the spring preload and refills the fork with premium suspension fluid. Then the buyer is issued this unusual guarantee: If he isn’t completely satisfied with the suspension’s performance, White Bros, will continue to readjust the unit until he’s happy.

I didn’t find it necessary to use this service, though, for the WP fork I now have is the best off-road front suspension I’ve ever tried. The damping is smooth, controlled and comfortable at one mph or 100 mph, on virtually any type of terrain; rocks, whoops of all sorts, virgin desert, and fast, cobby trails all are magically soaked up without jarring the rider or pitching the bike around.

Another benefit of this fork is an increase in the steering precision. The strong triple-clamps pinch tightly around huge, 54mm top legs, while the axle is held solidly by double pinch bolts at each lower leg. The result is instant steering input from handlebar to front wheel. Nothing flexes or twists with the upside-down design. And the extremely short extension of the lower fork legs below the axle lessens the chance of snagging a leg on a rock or rain rut.

After the fork was finished, I had a multitude of little changes to complete. like the switch to a Husky Products LR-bend handlebar. Uptite makes some footpegs that are much better than stock, as well as aluminum radiator-hose T-fittings that don’t break and leave you boiling mad in the middle of nowhere, as the Stockers are known to do (available from Uptite Products, [714] 8357277). After a year of experimenting with exhaust systems on last year’s 510, I settled on Cobra’s two-intoone pipes (from Cobra at [714] 7795318) that offer a power increase over virtually the entire powerband. And from Acerbis, I got the plastic parts—a front fender and fender brace, handguards and a headlight assembly with halogen bulb. The side panels I had to make myself from a sheet of plastic; the Stockers made the bike too wide just below the seat.

Of course, most of these modifications aren’t exactly cheap. But the overall finished machine still cost a lot less than the 1983 Honda XR500 Lite project bike I built a few years ago (Cycle World, October 1984). And having the ultimate, personalized off-road motorcycle is what a project bike is all about.

Besides, I wouldn’t be caught dead owning a stock anything.

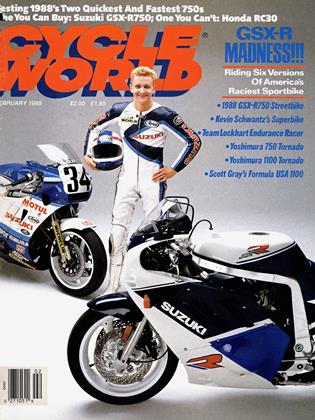

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsBad Raps And Bad Reps

FEBRUARY 1988 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsRaised Standards

FEBRUARY 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

FEBRUARY 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupNew Allies In the Atv Wars

FEBRUARY 1988 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

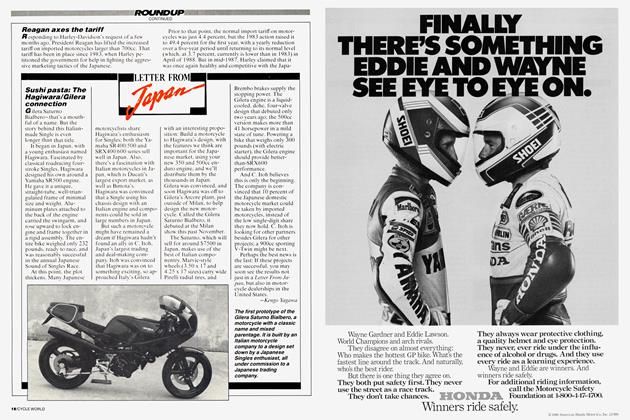

RoundupLetter From Japan

FEBRUARY 1988 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

FEBRUARY 1988 By Alan Cathcart