Engineers

AT LARGE

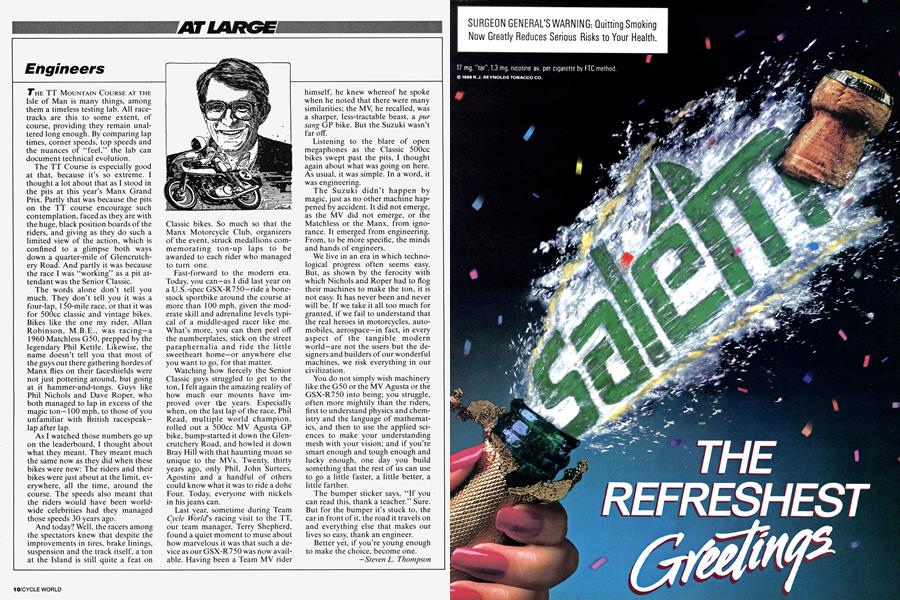

THE TT MOUNTAIN COURSE AT THE Isle of Man is many things, among them a timeless testing lab. All racetracks are this to some extent, of course, providing they remain unaltered long enough. By comparing lap times, corner speeds, top speeds and the nuances of “feel,” the lab can document technical evolution.

The TT Course is especially good at that, because it’s so extreme. I thought a lot about that as I stood in the pits at this year’s Manx Grand Prix. Partly that was because the pits on the TT course encourage such contemplation, faced as they are with the huge, black position boards of the riders, and giving as they do such a limited view of the action, which is confined to a glimpse both ways down a quarter-mile of Glencrutchery Road. And partly it was because the race I was “working” as a pit attendant was the Senior Classic.

The words alone don’t tell you much. They don’t tell you it was a four-lap, 150-mile race, or that it was for 500cc classic and vintage bikes. Bikes like the one my rider, Allan Robinson, M.B.E., was racing—a 1960 Matchless G50, prepped by the legendary Phil Kettle. Likewise, the name doesn’t tell you that most of the guys out there gathering hordes of Manx flies on their faceshields were not just pottering around, but going at it hammer-and-tongs. Guys like Phil Nichols and Dave Roper, who both managed to lap in excess of the magic ton—100 mph, to those of you unfamiliar with British racespeak— lap after lap.

As I watched those numbers go up on the leaderboard, I thought about what they meant. They meant much the same now as they did when these bikes were new: The riders and their bikes were just about at the limit, everywhere, all the time, around the course. The speeds also meant that the riders would have been worldwide celebrities had they managed those speeds 30 years ago.

And today? Well, the racers among the spectators knew that despite the improvements in tires, brake linings, suspension and the track itself, a ton at the Island is still quite a feat on Classic bikes. So much so that the Manx Motorcycle Club, organizers of the event, struck medallions commemorating ton-up laps to be awarded to each rider who managed to turn one.

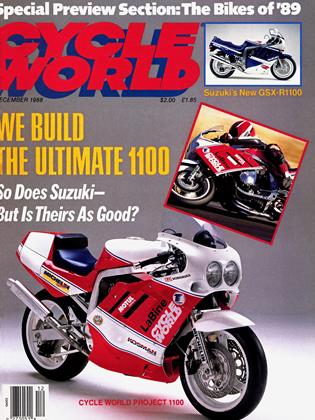

Fast-forward to the modern era. Today, you can—as I did last year on a U.S.-spec GSX-R750—ride a bonestock sportbike around the course at more than 100 mph, given the moderate skill and adrenaline levels typical of a middle-aged racer like me. What’s more, you can then peel off the numberplates, stick on the street paraphernalia and ride the little sweetheart home—or anywhere else you want to go, for that matter.

Watching how fiercely the Senior Classic guys struggled to get to the ton, I felt again the amazing reality of how much our mounts have improved over the years. Especially when, on the last lap of the race, Phil Read, multiple world champion, rolled out a 500cc MV Agusta GP bike, bump-started it down the Glencrutchery Road, and howled it down Bray Hill with that haunting moan so unique to the MVs. Twenty, thirty years ago, only Phil, John Surtees, Agostini and a handful of others could know what it was to ride a dohc Four. Today, everyone with nickels in his jeans can.

Last year, sometime during Team Cycle World’s racing visit to the TT, our team manager, Terry Shepherd, found a quiet moment to muse about how marvelous it was that such a device as our GSX-R750 was now available. Having been a Team MV rider

himself, he knew whereof he spoke when he noted that there were many similarities; the MV, he recalled, was a sharper, less-tractable beast, a pur sang GP bike. But the Suzuki wasn’t far off.

Listening to the blare of open megaphones as the Classic 500cc bikes swept past the pits, I thought again about what was going on here. As usual, it was simple. In a word, it was engineering.

The Suzuki didn’t happen by magic, just as no other machine happened by accident. It did not emerge, as the MV did not emerge, or the Matchless or the Manx, from ignorance. It emerged from engineering. From, to be more specific, the minds and hands of engineers.

We live in an era in which technological progress often seems easy. But, as shown by the ferocity with which Nichols and Roper had to flog their machines to make the ton, it is not easy. It has never been and never will be. If we take it all too much for granted, if we fail to understand that the real heroes in motorcycles, automobiles, aerospace—in fact, in every aspect of the tangible modern world—are not the users but the designers and builders of our wonderful machines, we risk everything in our civilization.

You do not simply wish machinery like the G50 or the MV Agusta or the GSX-R750 into being; you struggle, often more mightily than the riders, first to understand physics and chemistry and the language of mathematics, and then to use the applied sciences to make your understanding mesh with your vision; and if you’re smart enough and tough enough and lucky enough, one day you build something that the rest of us can use to go a little faster, a little better, a little farther.

The bumper sticker says, “If you can read this, thank a teacher.” Sure. But for the bumper it’s stuck to, the car in front of it, the road it travels on and everything else that makes our lives so easy, thank an engineer.

Better yet, if you’re young enough to make the choice, become one.

Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialAdios, Specialization

December 1988 By Paul Dean -

Learnings

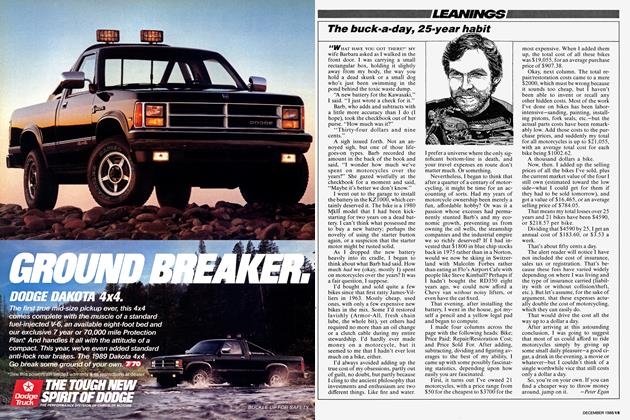

LearningsThe Buck-A-Day, 25-Year Habit

December 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1988 -

Roundup

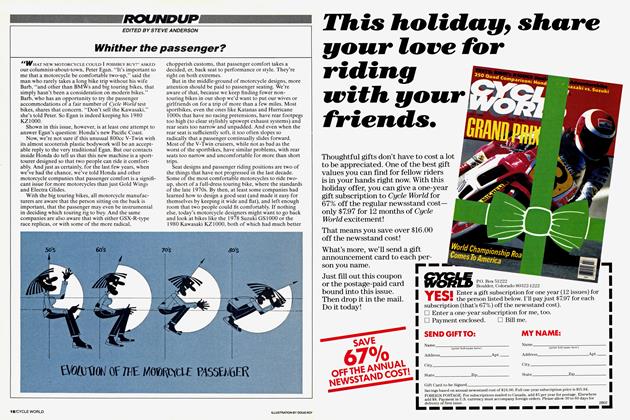

RoundupWhither the Passenger?

December 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

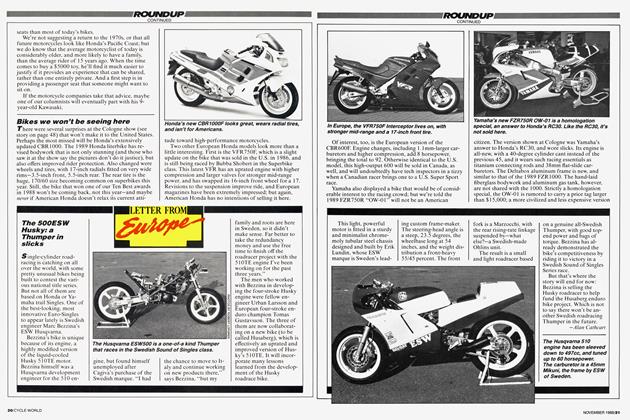

RoundupLetter From Europe

December 1988 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupDestinations

December 1988 By Steve Anderson