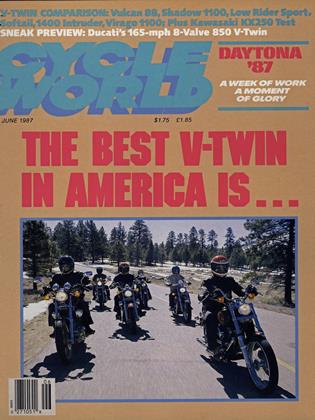

V-TWIN TOURING

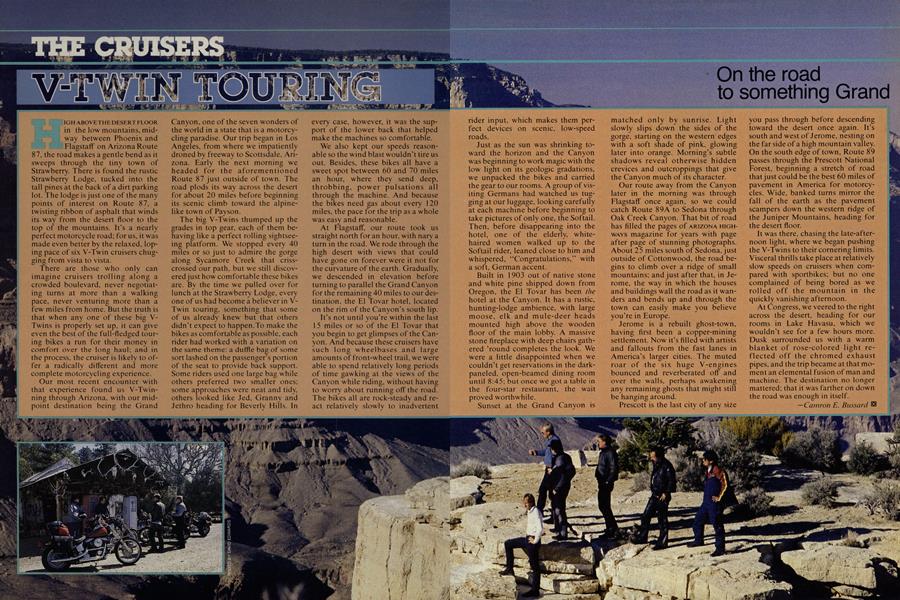

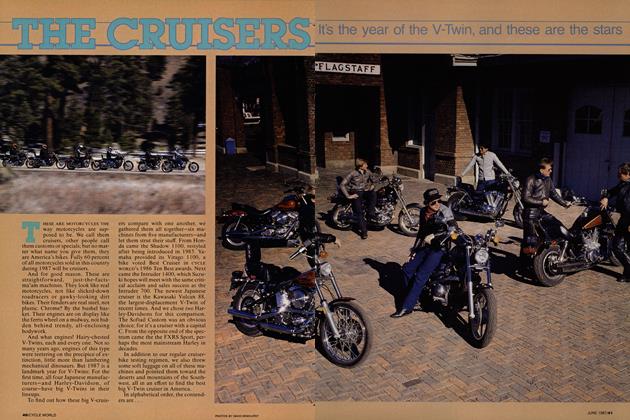

HIGH ABOVE THE DESERT FLOOR in the low mountains, midway between Phoenix and Flagstaff_on Arizona Route 87, the road makes a gentle bend as it sweeps through the tiny town of Strawberry. There is found the rustic Strawberry Lodge, tucked into the tall pines at the back of a dirt parking lot. The lodge is just one of the many points of interest on Route 87, a twisting ribbon of asphalt that winds its way from the desert floor to the top of the mountains. It’s a nearly perfect motorcycle road; for us, it was made even better by the relaxed, loping pace of six V-Twin cruisers chugging from vista to vista.

There are those who only can imagine cruisers trolling along a crowded boulevard, never negotiating turns at more than a walking pace, never venturing more than a few miles from home. But the truth is that when any one of these big VTwins is properly set up, it can give even the best of the full-fledged touring bikes a run for their money in comfort over the long haul; and in the process, the cruiser is likely to offer a radically different and more complete motorcycling experience.

Our most recent encounter with that experience found us V-Twinning through Arizona, with our midpoint destination being the Grand

Canyon, one of the seven wonders of the world in a state that is a motorcycling paradise. Our trip began in Los Angeles, from where we impatiently droned by freeway to Scottsdale, Arizona. Early the next morning we headed for the aforementioned Route 87 just outside of town. The road plods its way across the desert for about 20 miles before beginning its scenic climb toward the alpinelike town of Payson.

The big V-Twins thumped up the grades in top gear, each of them behaving like a perfect rolling sightseeing platform. We stopped every 40 miles or so just to admire the gorge along Sycamore Creek that crisscrossed our path, but we still discovered just how comfortable these bikes are. By the time we pulled over for lunch at the Strawberry Lodge, every one of us had become a believer in VTwin touring, something that some of us already knew but that others didn’t expect to happen.To make the bikes as comfortable as possible, each rider had worked with a variation on the same theme: a duffle bag of some sort lashed on the passenger’s portion of the seat to provide back support. Some riders used one large bag while others preferred two smaller ones; some approaches were neat and tidy, others looked like Jed, Granny and Jethro heading for Beverly Hills. In

every case, however, it was the support of the lower back that helped make the machines so comfortable.

We also kept our speeds reasonable so the wind blast wouldn’t tire us out. Besides, these bikes all have a sweet spot between 60 and 70 miles an hour, where they send deep, throbbing, power pulsations all through the machine. And because the bikes need gas about every 120 miles, the pace for the trip as a whole was easy and reasonable.

At Flagstaff, our route took us straight north for an hour, with nary a turn in the road. We rode through the high desert with views that could have gone on forever were it not for the curvature of the earth. Gradually, we descended in elevation before turning to parallel the Grand Canyon for the remaining 40 miles to our destination, the El Tovar hotel, located on the rim of the Canyon’s south lip.

It’s not until you’re within the last 15 miles or so of the El Tovar that you begin to get glimpses of the Canyon. And because these cruisers have such long wheelbases and large amounts of front-wheel trail, we were able to spend relatively long periods of time gawking at the views of the Canyon while riding, without having to worry about running off the road. The bikes all are rock-steady and react relatively slowly to inadvertent rider input, which makes them perfect devices on scenic, low-speed roads.

On the road to something Grand

Just as the sun was shrinking toward the horizon and the Canyon was beginning to work magic with the low light on its geologic gradations, we unpacked the bikes and carried the gear to our rooms. A group of visiting Germans had watched us tugging at our luggage, looking carefully at each machine before beginning to take pictures of only one, the Softail. Then, before disappearing into the hotel, one of the elderly, whitehaired women walked up to the Softail rider, leaned close to him and whispered, “Congratulations,” with a soft, German accent.

Built in 1903 out of native stone and white pine shipped down from Oregon, the El Tovar has been the hotel at the Canyon. It has a rustic, hunting-lodge ambience, with large moose, elk and mule-deer heads mounted high above the wooden floor of the main lobby. A massive stone fireplace with deep chairs gathered ’round completes the look. We were a little disappointed when we couldn’t get reservations in the darkpaneled, open-beamed dining room until 8:45; but once we got a table in the four-star restaurant, the wait proved worthwhile.

Sunset at the Grand Canyon is matched only by sunrise. Light slowly slips down the sides of the gorge, starting on the western edges with a soft shade of pink, glowing later into orange. Morning’s subtle shadows reveal otherwise hidden crevices and outcroppings that give the Canyon much of its character.

Our route away from the Canyon later in the morning was through Flagstaff once again, so we could catch Route 89A to Sedona through Oak Creek Canyon. That bit of road has filled the pages of ARIZONA HIGHWAYS magazine for years with page after page of stunning photographs. About 25 miles south of Sedona, just outside of Cottonwood, the road begins to climb over a ridge of small mountains; and just after that, in Jerome, the way in which the houses and buildings wall the road as it wanders and bends up and through the town can easily make you believe you’re in Europe.

Jerome is a rebuilt ghost-town, having first been a copper-mining settlement. Now it’s filled with artists and fallouts from the fast lanes in America’s larger cities. The muted roar of the six huge V-engines bounced and reverberated off and over the walls, perhaps awakening any remaining ghosts that might still be hanging around.

Prescott is the last city of any size you pass through before descending toward the desert once again. It’s south and west of Jerome, nesting on the far side of a high mountain valley. On the south edge of town, Route 89 passes through the Prescott National Forest, beginning a stretch of road that just could be the best 60 miles of pavement in America for motorcycles. Wide, banked turns mirror the fall of the earth as the pavement scampers down the western ridge of the Juniper Mountains, heading for the desert floor.

It was there, chasing the late-afternoon light, where we began pushing the V-Twins to their cornering limits. Visceral thrills take place at relatively slow speeds on cruisers when compared with sportbikes; but no one complained of being bored as we rolled off the mountain in the quickly vanishing afternoon.

At Congress, we veered to the right across the desert, heading for our rooms in Lake Havasu, which we wouldn’t see for a few hours more. Dusk surrounded us with a warm blanket of rose-colored light reflected off the chromed exhaust pipes, and the trip became at that moment an elemental fusion of man and machine. The destination no longer mattered; that it was farther on down the road was enough in itself.

Camron E. Bussard

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialA Crash Course In Career Counseling

June 1987 By Paul Dean -

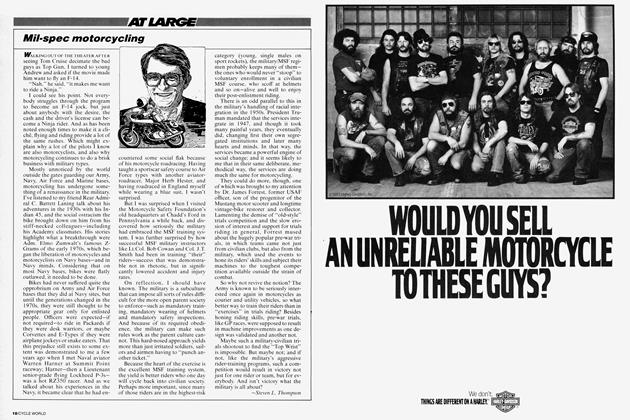

At Large

At LargeMil-Spec Motorcycling

June 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Shape of Things To Come

June 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

June 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

June 1987 By Alan Cathcart