KING of the QUARTER

FEATURES

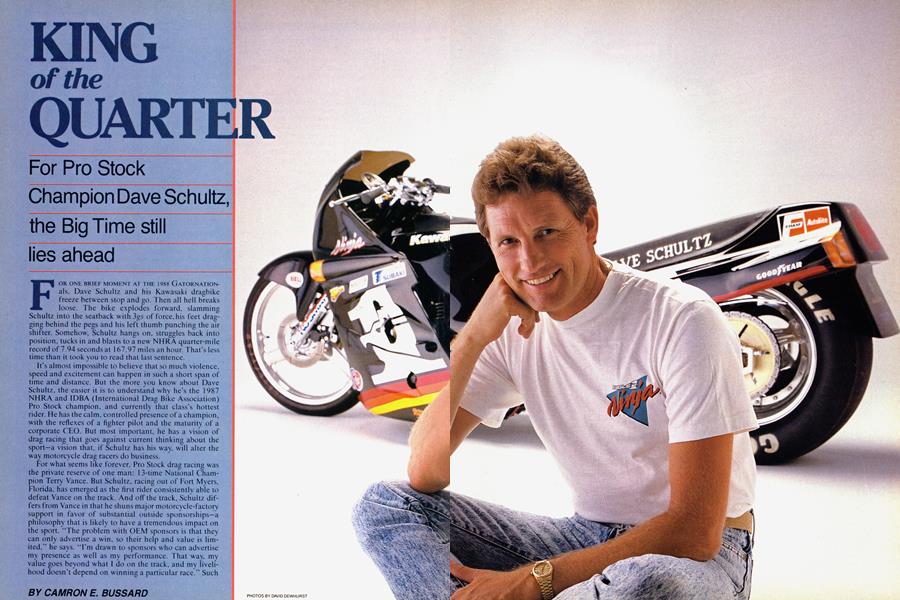

For Pro Stock Champion Dave Schultz, the Big Time still lies ahead

FOR ONE BRIEF MOMENT AT THE 1988 GATORNATIONals, Dave Schultz and his Kawasaki dragbike freeze between stop and go. Then all hell breaks loose. The bike explodes forward, slamming Schultz into the seatback with 3gs of force, his feet dragging behind the pegs and his left thumb punching the air shifter, Somehow, Schultz hangs on, struggles back into position. tucks in and blasts to a new NHRA quarter-mile record of 7.94 seconds at 167.97 miles an hour. That's less time than it took you to read that last sentence.

It’s almost impossible to believe that so much violence, speed and excitement can happen in such a short span of time and distance. But the more you know about Dave Schultz, the easier it is to understand why he’s the 1987 NHRA and IDBA (International Drag Bike Association) Pro Stock champion, and currently that class’s hottest rider. He has the calm, controlled presence of a champion, with the reflexes of a fighter pilot and the maturity of a corporate CEO. But most important, he has a vision of drag racing that goes against current thinking about the sport—a vision that, if Schultz has his way, will alter the way motorcycle drag racers do business.

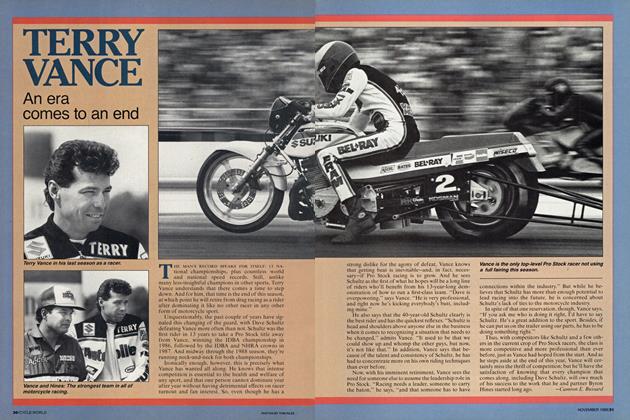

For what seems like forever. Pro Stock drag racing was the private reserve of one man: 13-time National Champion Terry Vance. But Schultz, racing out of Fort Myers, Florida, has emerged as the first rider consistently able to defeat Vance on the track. And off the track, Schultz differs from Vance in that he shuns major motorcycle-factory support in favor of substantial outside sponsorships-a philosophy that is likely to have a tremendous impact on the sport. “The problem with OEM sponsors is that they can only advertise a win. so their help and value is limited,” he says. “I’m drawn to sponsors who can advertise my presence as well as my performance. That way, my value goes beyond what I do on the track, and my livelihood doesn’t depend on winning a particular race.” Such thinking is prevalent among NHRA automobile competitors but is unheard of in motorcycling drag racing, where winning is key to survival.

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

123

When he talks about potential sponsors, Schultz mentions familiar names like Tide, Hawaiian Punch and the oil companies, all corporations with huge advertising budgets. "I want to market drag racing outside of the sport," he says. “ I want it to be more than a large club race."

Schultz’s approach to racing is strictly first-class, which makes him very attractive to possible backers. His sponsor this year is Eagle One, a manufacturer of car-care products, which keeps him busy going to auto shows and expositions throughout the year promoting the company’s goods. As part of the deal, his spectacular 68-foot tractor and trailer are painted in the knockout Eagle One colors, a virtual custom-built, rolling billboard for his sponsors.

Schultz has a lot going for him right now, but other than having a much larger budget, his overall attitude hasn't changed much from when he first started drag-racing cars for fun in 1974. When his high-tech automotive repair business began taking more of his time, though, he stopped racing cars, and by 1976 had switched to motorcycles. “I didn’t want my profession and my hobby to be one and the same, but I had to get racing out of my system,’’ he recalls. “I started with a two-stroke Kawasaki 400, and before I knew it, I had that thing into the 10s, and set a record of 121 miles an hour with it.”

Throughout the Seventies and into the Eighties, Schultz stayed with bike drag-racing, but strictly for recreation; in his mind, weekends were for enjoyment. He continued to campaign Kawasakis, including the 750cc two-stroke Triples. Of that period Schultz says, “I think I irritated people more than I made them my friends because 1 took racing so casually. I won when I raced, and because I was riding bikes that everyone said were not competitive, 1 kind of salted their wounds.”

Schultz turned pro in 1985, and began taking matters a little more seriously. But when he tried to line up sponsors, they all wanted to see a championship before parting with any money. So, in 1986, Schultz set national ET and MPH records at each event on the way to becoming the IDBA champion. Then, as the 1987 season drew to a close, he found himself in a close battle for the prestigious NHRA championship with the reigning champ, the seemingly invincible Vance.

That season’s outcome went down to the last meet, which Schultz won. But that particular championship chase was more than just Vance versus Schultz and Suzuki versus Kawasaki; it was the first time in years that Vance had lost the NHRA championship. And it marked the beginning of the end of Vance/Suzuki dominance of Pro Stock drag racing, although, ironically enough, Schultz had bought his modified Kawasaki engines—and still does, for that matter—from Terry Vance’s company, Vance & Hines Racing.

Schultz’s decision to race a Kawasaki rather than a Suzuki was easy. “I’m a loyalist,” he claims. “I have never raced anything but Kawasakis.” So. when others thought the two-valve Kawasaki engine was dead, he convinced the mechanical half of Vance & Hines Racing, Byron Hines, to try to squeeze more power out of it. The latest manifestation of Hines’ efforts is an air-cooled, over-210horsepower hybrid of Kawasaki parts based on 903cc Z-l engine cases fitted with a GPzl 100 top end punched-out to 1 134cc. “We use the best parts from each and make a better engine,” says Schultz. “I bought my 7.94 engine in 1984, and it’s still going strong.”

Currently, Schultz spends about $25,000 a year at VHR. and counts on Hines—considered by most to be the premier builder of motorcycle drag-racing motors—to make his engines as fast and reliable as possible. But their relationship goes beyond money, as exemplified by what happened earlier in the season after Schultz broke both wrists working around the house. When Hines learned that Schultz was considering racing that weekend, he paid him a visit. “I told him if he tried to race, he wouldn’t get his next motor on time." recalls Hines. The concern shown by Hines persuaded Schultz to hold off until his wrists had healed a bit more. “Even though Byron really is my competitor," he says, “1 trust him. because he has more intégrité than anyone I know."

Hines also helped convince Schultz that even though the older Kawasaki engines don't have the horsepower potential of the newer ones—particularly the Kawasaki ZX-10 engine—they are considerably stronger, especially in the transmission and crankshaft. “I would love to use the ZX-10 engine."says Schultz, “but when you hook up 200 horsepower to a 10-inch-wide slick, rev the engine to 8000 rpm and dump the clutch, you're either going to accelerate or break. The new engines will break."

While the two-valve engine may seem low-tech by today’s production-bike standards, the rest of the bike is as specialized and sophisticated as a factory GP roadracer— even more so. in the case of the on-board Race Pak computer Schultz uses. The computer has no control func-

tions, but simply collects data, monitoring over 1 1 functions on each pass, including air flow around and through the fairing, wheelspin, g-forces and even lean angles of the bike. After each run, Schultz examines a readout of the collected information, giving him an objective base from which to work; it also gives him an edge over those who still rely on observers for vital feedback.

And, since competitors can. for the first time in Pro Stock racing, use a specially designed chassis rather than a modified production unit, Schultz runs a Kosman Racing Pro Stock Replica rigid-rear frame mated to a front fork and wheels also made by Kosman. The frame is designed so that as much power as possible is transferred to the rear wheel on the launch. And the .5-gallon fuel tank is actually the backbone of the frame, holding just enough fuel for one complete run.

Covering the whole works is a fairing and bodywork that Schultz designed himself. Pro Stock rules dictate that the bike resemble a stock machine, so Schultz’s fairing is based on the Ninja 1000’s. It comprises Kevlar, carbon fiber and graphite bonded with epoxy resin, and weighs under 10 pounds. The original fairing cost Schultz about $14,000, but he now sells bodywork for Kawasakis and Suzukis—he designed the body on Vance's machine—for about $1500. He claims to have sold about 80 complete units, and has standing orders for more.

Schultz is the first rider to experiment with fully faired drag bikes, and so far, he has had the most success. The goal is to manage the air flow around and through the machine, and to this point it has been trial-and-error engineering. “Last year we changed the fairing four times, working on the shape and air management," he said. “I can still improve the design without wind-tunnel time, but we would be able to see large improvements much faster with it."

It’s clear that not all of Schultz’s attention has been focused on performance, because his bike itself is a thing of beauty. Polished aluminum pieces abound, and the paint has been flawlessly laid on by crew member Kenny Williams. Says Schultz, “If my bike isn’t ready to go either to the strip or to a show, I’m not ready to race." After every event, it is completely disassembled and cleaned by Schultz’s crew chief, his wife Meredith.

The attention to detail evident on Schultz’s machine is just one example of his almost fanatically thorough approach to racing. He believes that the guys who go the fastest are the ones who pay the best attention to details. As he puts it, “Enough pennies make a dollar."

And it's that attention to little things that makes Schultz so consistently tough on the track. “I'm usually a slow qualifier because I never stop trying new things. I think I’m a more deadly competitor coming from a lower qualifying position because I have to concentrate more on the little things.” Before each run, he disappears into his rig to clear his mind, and to try to imagine a complete run from the burnout to the finish line. “I do this over and over until I have made the perfect run in my mind. Then I’m ready. That perfect pass is what I want to remember when I slip on my leathers.”

Fortunately for Pro Stock racing, Schultz is more than just a talented racer. He’s a man who sees the sport as something more than the winning of championships and the setting of records—although he acknowledges that these are worthy enough goals. But he thinks that motorcycle racers have a lot to learn about professionalism and sponsorship from NHRA automobile racers like Kenny Bernstein, whose Top Fuel funny car has over a million bucks worth of backing. And when you consider that the NHRA draws overa million people at 14 events, this series gives motorcycle drag racers more exposure than any other motorcycle competition by far.

It makes sense, then, that Schultz talks of drag racing in terms of The Show, not just the competition. “The Show,” he says, “is what the spectators come to see, and what the sponsors have to sell.” That view runs counter to Vance’s belief that the leader of the sport has to keep tight relations within the motorcycling community if Pro Stock racing is to grow.

Schultz’s pragmatic view about sponsors also affects his ideas about the people in the grandstands, as well, for he sees a distinction between spectators and fans. “We are after the spectator, not the racing fan,” he says. “The fan knows what he wants to see, and will be there regardless. But the spectator is there to see The Show, and may not even be a motorcycle rider.” Considering Schultz’s ideas about the need to attract non-motorcycle sponsors, it's easy to understand why he feels “spectators” are so important. Still, he admits that the key is intense, top-level competition on the track. “After all,” he says, “it’s hard to draw crowds to a chess match.”

There are some who question not just Schultz's ideas, but also his commitment to drag racing and his motivations to push the sport upscale. He candidly responds. “I do have a commitment to the sport, but I can’t honestly say that I will always be here. As soon as this is just a job and is no longer fun, we’re out of here. Other things are

more important than racing, things like my family and my church. And there are more things I would like to do than I have the time for.”

For now, Schultz is proud of the contributions he has made to racing, and is convinced that the vision he has for the future of Pro Stock can only benefit the sport. He believes that drag racing is in many ways a profile sport, and its success comes in large part because the fans can get up close to the racers in the pits, and rub shoulders with their heroes. And he believes that The Show has to entertain the crowds with larger-than-life feats of courage and daring if those spectators are to return. He acknowledges that Terry Vance brought respectability to Pro Stock drag racing, but Schultz wants to take it even higher, with more money, more power and more independence given to the better riders and the successful teams.

“Ultimately,” Schultz admits, “I may not be around to see the rew-ards of what I am doing, but already things are beginning to change. Sponsors are asking me what I am doing next year, and if they can’t get me, they’ll get someone else.” The tremendous popularity of the bikes at the car-dominated NHRA events has convinced him that the big time is ready for motorcycle drag racing; the next couple of seasons will tell if the motorcycles are ready to step up the pace in sponsorship, professionalism and showmanship enough to become really big-time racing.

Schultz thinks all this will come to pass, so he's already moving in that direction; the rest will have to catch up if they hope to keep up. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialHumble Beginnings

NOVEMBER 1988 By Paul Dean -

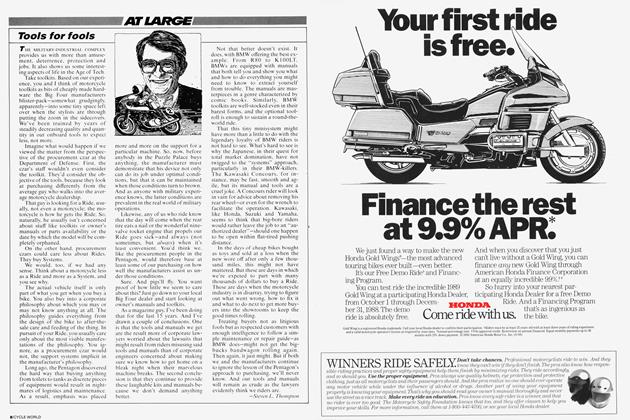

At Large

At LargeTools For Fools

NOVEMBER 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Importance of Being Earnest

NOVEMBER 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

NOVEMBER 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupElections 1988

NOVEMBER 1988 -

Letter From Japan

NOVEMBER 1988 By Koichi Hirose