MOTORCYCLES ON THE MALL

At last, a proud American heritage is acknowledged

STEVEN L. THOMPSON

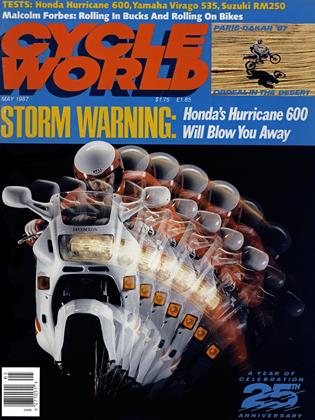

GIVEN THIS COUNTRY'S ATTItudes toward motorcycles over the years, it’s not surprising that two-wheelers have been poorly represented in the nation’s museums of history, even as simple artifacts. Not surprising, but irritating to those of us who know the special rewards of motorcycling, particularly to those who sense how significant those rewards were in the earliest years of the wheeled century. Thus, even a token gesture of acknowledgement is like an invigorating breeze on a stifling day; and when something comes along such as the motorcycle exhibit now on display in the Road Transportation Hall at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, the effect is magnified almost ludicrously.

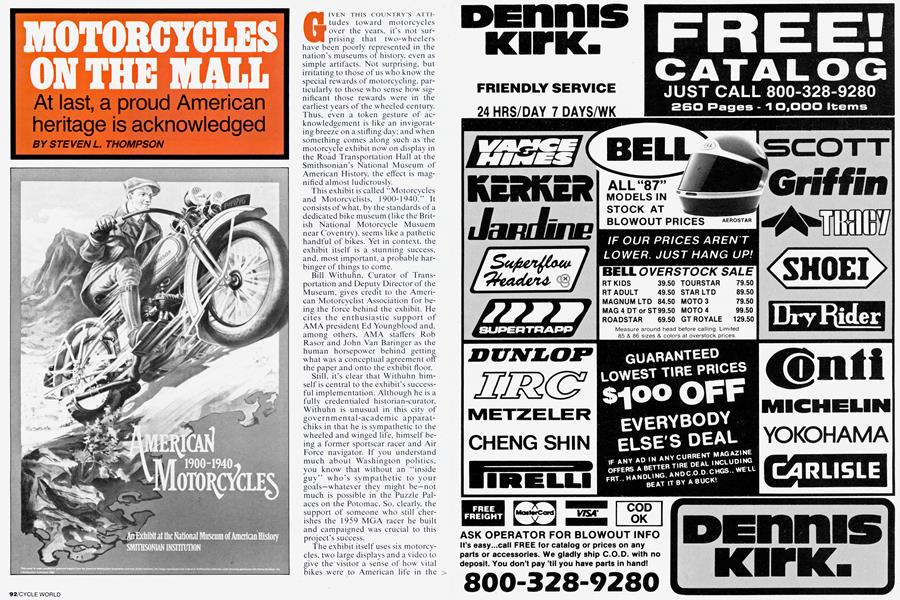

This exhibit is called “Motorcycles and Motorcyclists, 1900-1940.” It consists of what, by the standards of a dedicated bike museum (like the British National Motorcycle Musuem near Coventry), seems like a pathetic handful of bikes. Yet in context, the exhibit itself is a stunning success, and, most important, a probable harbinger of things to come.

Bill Withuhn, Curator of Transportation and Deputy Director of the Museum, gives credit to the American Motorcyclist Association for being the force behind the exhibit. He cites the enthusiastic support of AMA president Ed Youngblood and, among others, AMA staffers Rob Rasor and John Van Baringer as the human horsepower behind getting what was a conceptual agreement off the paper and onto the exhibit floor.

Still, it’s clear that Withuhn himself is central to the exhibit’s successful implementation. Although he is a fully credentialed historian-curator, Withuhn is unusual in this city of governmental-academic apparatchiks in that he is sympathetic to the wheeled and winged life, himself being a former sportscar racer and Air Force navigator. If you understand much about Washington politics, you know that without an “inside guy” who's sympathetic to your goals—whatever they might be—not much is possible in the Puzzle Palaces on the Potomac. So, clearly, the support of someone who still cherishes the 1959 MGA racer he built and campaigned was crucial to this project’s success.

The exhibit itself uses six motorcycles, two large displays and a video to give the visitor a sense of how vital bikes were to American life in the first 40 years of the century. The five main display bikes—a 1902 Indian Single, a 1914 Harley-Davidson 1 1K board-track racer, a 1918 Cleveland touring bike, a 1923 Indian Chief with a Princess sidecar, and the 1937 H-D world speed record bike used by Joe Petrali at Daytona to go 1 36.1 83 mph—give the museum-goer a good idea of the shape of that past.

But perhaps today’s motorcyclists will be intrigued most by the addition to the exhibit of a sixth bike: Charley Perethian’s 1982 Vetter High-Mileage Contest winner powered by a 185cc Yamaha engine. Withuhn grins when asked why this modern machine is displayed alongside historic oldtimers, and says that the spirit and concept of Perethian’s bike are entirely in keeping with that of the others. Eyes twinkling, he’ll then point out that standing only a few feet from the Petrali racer—although not a part of the 1 900-1940 exhibit— his museum has what he believes to be th e oldest motorcycle in the world: the 1869 Roper Steam Velocipede. which looks remarkably trim and sleek compared to the “official” title-holder, the Gottlieb Daimler monstrosity.

The value of these bikes being on display at the Smithsonian lies in their context. You can go to many a concours and see better-restored vehicles, in numbers that'll make you dizzy; but only at a museum like this one can you begin to catch the meaning of the bikes. Around them are cars of their eras, and elsewhere in the museum are well-described displays and other artifacts, from clothes to printing presses and weapons, that combine to help put the motorcycles in the proper perspective. In this regard, the small but superb collection of moto-memorabilia assembled by Withuhn and the AMA, and arranged by the museum’s exhibit designer, Russ Cashdollar, provide just the right flavoring for understanding who the people were, what they did with their bikes and, perhaps, even why.

Aiding immensely in the latter is the exhibit’s video made by the AMA about early American racing. That five-minute repeating tape focuses on celebrated H-D racer Jim Davis, whose commentary on the highlighted 1 923 Dodge City 300 makes a modern motorcyclist realize that some things —like racers —never change, no matter what bikes they ride or what clothes they wear.

Yet some things about motorcycling do change; that much is made obvious by Withuhn’s reply when asked why he chose 1940 as the cutoff date for the exhibit. It came

down, he said, to matters of practicality—such as available floor space (he’s used about 20 percent of his entire Road Transportation Hall for the bikes alone, which is why the exhibit must come down on August 27th of 1987)—as well as to matters of history. Before World War II, he pointed out, motorcycles were considered viable alternatives to cars as means of transportation; but after the war—at least in America—they were not, as the postwar boom made it possible for just about every American to own a car.

Nevertheless, Withuhn acknowledged that a most compelling reason for making 1940 the cutoff point can be summarized by a single word: Hollister. The infamous terrorizing of that small California town by a bunch of motorcycle hoodlums in 1947 became the impetus for Marlon Brando’s later screen transformation of the image of motorcyclists, and for all the subsequent social ostracism that ensued.

Withuhn, as a historian, is well-acquainted with this event and its effects; and he states plainly that in itself, this country’s reversal of its views of motorcycling warranted not just further serious study, but documentation and explanation in a future museum exhibit. That exhibit, however, like the many others involving America's love/hate affair with all forms of automotion, will have to wait—not just for what might be termed a “power constituency” to fund and drive it inside the labyrinthine Washington bureaucracy, but also for someplace to hold it. The current National Museum of American History, built in 1959. is simply and ironically too small to tell more than a small part of the incredible story of Americans and their wheels.

But even that small part is compelling. And no motorcyclist—indeed, no American—should fail to visit the museum to discover the rich world of those who made our Interceptors and Low Riders and Daytona 200 possible and, perhaps, inevitable. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue