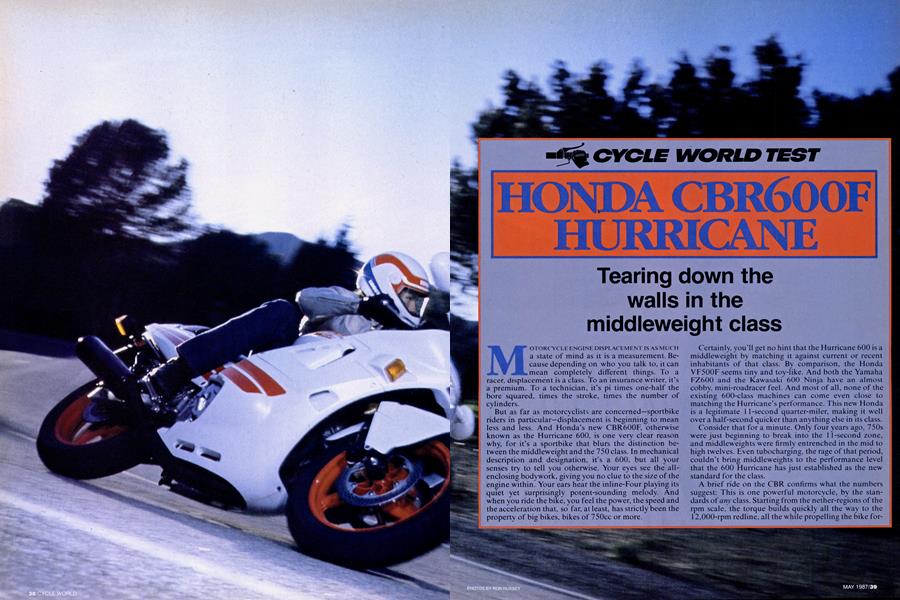

HONDA CBR600F HURRICANE

CYCLE WORLD TEST

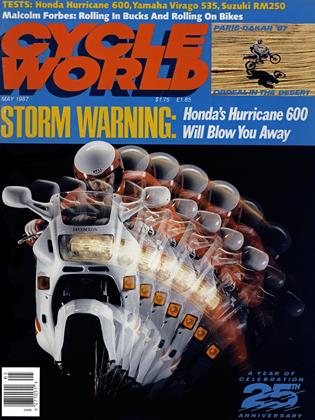

Tearing down the walls in the middleweight class

MOTORCYCLE ENGINE DISPLACEMENT IS AS MUCH a state of mind as it is a measurement. Be cause depending on who you talk to, it can mean completely different things. To a racer, displacementis a ëlass. To an insurance writer, it's a premium. To a technician, it's pi times one-half the bore squared, times the stroke, times the number of cylinders.

But as far as motorcyclists are concerned—sportbike riders in particular—displacement is beginning to mean less and less. And Honda’s new CBR600F, otherwise known as the Hurricane 600, is one very clear reason why, for it’s a sportbike that blurs the distinction between the middleweight and the 750 class. In mechanical description and designation, it’s a 600, but all your senses try to tell you otherwise. Your eyes see the allenclosing bodywork, giving you no clue to the size of the engine within. Your ears hear the inline-Four playing its quiet yet surprisingly potent-sounding melody. And when you ride the bike, you feel the power, the speed and the acceleration that, so far, at least, has strictly been the property of big bikes, bikes of 750cc or more.

Certainly, you’ll get no hint that the Hurricane 600 is a middleweight by matching it against current or recent inhabitants of that class. By comparison, the Honda VF500F seems tiny and toy-like. And both the Yamaha FZ600 and the Kawasaki 600 Ninja have an almost cobby, mini-roadracer feel. And most of all, none of the existing 600-class machines can come even close to matching the Hurricane’s performance. This new Honda is a legitimate 1 1-second quarter-miler, making it well over a half-second quicker than anything else in its class.

Consider that for a minute. Only four years ago, 750s were just beginning to break into the 1 1-second zone, and middleweights were firmly entrenched in the mid to high twelves. Even tubocharging, the rage of that period, couldn’t bring middleweights to the performance level that the 600 Hurricane has just established as the new standard for the class.

A brief ride on the CBR confirms what the numbers suggest: This is one powerful motorcycle, by the standards of any class. Starting from the nether-regions of the rpm scale, the torque builds quickly all the way to the 12,000-rpm redline, all the while propelling the bike forward at near-literbike velocity. The Hurricane accelerates promply up to about 132 mph, and then creeps up to its 134 top speed rather slowly. But once again, that’s a level that would have been considered good for a 1000 just a few years ago.

For an engine with such remarkable performance, its technical credentials seem oddly ««remarkable. Removing the engine cowling reveals an unimpressive-looking powerplant that looks more like an industrial pump of some sort. The design of the engine follows the welltraveled path of the dohc, 16-valve, liquid-cooled inlineFour. The horsepower, therefore, comes strictly from good engineering, from providing relatively straight intake tracts and keeping friction-loss to a minimum.

It’s important to know that Honda’s goal with the CBR wasn’t simply to build the fastest motorcycle around, but to build the fastest, most affordable motorcycle around. That’s why Honda abandoned the rather difficult-to-produce V-Four configuration. A second cost-saving feature is the use of a cam chain. For the Japanese domestic market, this would be unacceptable; all of Honda’s recent home-market sportbikes have used gears to drive the cams. But according to Honda, gears add about 4.4 pounds to the bike and $200 to the retail price. And according to an American Honda spokesman, leaving the engine’s appearance in the unfinished state may have saved $200 on retail, compared to the normal buffed and painted engines we’ve seen in the past.

THE MISSING LINK IN THE CBR FAMILY

Here in the States, Honda's CBR line is limited to the 600 and the 1000. But there are others. First came the CBR400, and now there's the CBR75O, pictured here. Called the Super Aero, the CBR 750 is targeted at the Japanese domestic market, and is therefore somewhat detuned to meet government restrictions. In virtually all measurements, the machine falls between the 600 and the 1000. Don't look for it stateside, though; American Honda feels the VFR75OF is more than adequate to deal with the 750 market.

Yet another cost-saver is having the generator on the end of the crank. This makes the engine a few inches wider; but it increases crankshaft inertia and probably results in an overall weight saving because the crankshaft itself can be relatively lighter. And no gears or chains are required to drive the generator. Also, the CBR uses a cable-controlled clutch, which is lighter, cheaper, and offers better feel than Honda’s hydraulic clutches; it’s sole penalty is that it isn't self-adjusting.

When it came to the finish, though, Honda turned around and respent much of the cost that was saved in the engine. The Hurricane’s appearance is nothing short of breath-taking, for its plastic body parts completely enclose its unfinished engine. And unlike Japanese fairings in the past, the Honda’s is constructed of thick, wellrounded material, nothing light or flimsy. The elaborately sculptured bodywork also makes the CBR600 an aerodynamically slick package. The company claims the bike has three-percent less drag than a Ninja 600.

Perhaps more important is the increased attention paid to internal air flow once the air has passed through one of the fairing orifices; Honda has provided escape routes so air can flow through the machine. The most obvious result of the bodywork, though, is that the overall lines of the machine are downright sexy. As one admirer put it, whoever designed the Hurricane has an appreciation for pretty women. That perhaps slightly sexist remark sums up the Hurricane well. The lines are smooth, the finish is excellent and the overall package leaves the viewer with a feeling of admiration.

Aside from looks, though, there’s a lot to admire about the Hurricane—including its outstanding brakes. In fact, once we got used to the twin-piston, double-disc front brake on the CBR. we suddenly started wondering if there was something wrong with the brakes on just about everything else we rode. A single finger on the front brake lever is all we ever needed to slow down. The rear brake is good, too. but hardly ever necessary. During our 60-mph braking tests, in fact, the rear brake contributed very little to the CBR’s 121-foot stopping distance, primarily because the rear wheel wasn’t even on the ground for half that distance. That’s because the Hurricane has more weight on its front wheel than on the rear, even with the fuel tank empty.

That front-end weight bias has an effect on handling, as well. When cornering, you don’t have to lean forward over the tank and weight the front wheel to help the Hurricane turn, because there’s already enough weight up there. You do have to provide considerable handlebar input, though. The steel-framed Hurricane has wide, 17inch wheels, front and rear, and the steering is noticeably heavy. Nothing unreasonable, mind you, and the Hurricane certainly would have been considered an ultraquick-handling racer-replica just a few years ago. But since the advent of the 16-inch front wheel, the Hurricane ranks a bit on the slow-handling side.

That’s especially noticeable when you compare the Honda to the current class handling champ, the Yamaha FZ600. On a twisty road at a quick pace, the Yamaha seems ever-willing to dart and dive from corner to corner, while bending the Honda through the turns requires deliberate negotiation. And the same CBR front end that seemed so willing to stick to the asphalt at low speed seems just the opposite as the pace increases, always making you feel like the limits of traction are much nearer than they really are. So as you push harder and harder, the Honda becomes less and less perfect.

That’s not really surprising, though; the Hurricane wasn’t designed for the track. Instead, it is the only current 600-class sportbike whose design reflects a significant concern for cost and comfort. The seat, for example, is relatively plush—a veritable bean-bag compared to the FZ600’s seat—but still too thin for long-trip comfort. The handlebars are on the tall side for a true sportbike, so even though the footpegs are rather high, the seating postion is the most spread-out of any 600 short of a Yamaha Radian.

In suspension, too, the CBR was designed less for the racetrack, more for the steet. The ride is smooth and comfortable by sportbike standards, even if the rear end is a little stiff. Honda has made use of some clever engineering techniques in designing the rear suspension system, most notably the tire-hugging rear fender. This design so dramatically increases air flow around the rear shock, that the damper’s normal operating temperature is only about 104 degrees F, compared to 176 degrees for the much more shrouded VFR750F design. It’s one reason the rear suspension of the CBR600 is superior to the VFR’s, and much more fade-resistant.

Honda also tossed out its rather dated notion of using a single washer stack to control both compression and rebound damping in the Showa shock. The two damping functions now are controlled by separate stacks, enabling Honda’s engineers to be much more precise about damping rates.

When it comes to the reasons that the Hurricane works so well, though, what matters more than how Honda did it is that Honda did it. The Hurricane is a rational middleweight sportbike that demonstrates an almost irrational level of performance. Irrational, at least, by the old standards of middleweight sportbiking—the standards that seemed so impressive just four years ago.

But four years can be a very long time. For middleweight sportbikes, it’s been long enough to witness the passing of the era of the pocket rocket. And the dawn of the age of the 600cc Superbike. E3

HONDA

CBR600F HURRICANE

$3698

View Full Issue

View Full Issue