KAWASAKI GPz 750

CYCLE WORLD TEST

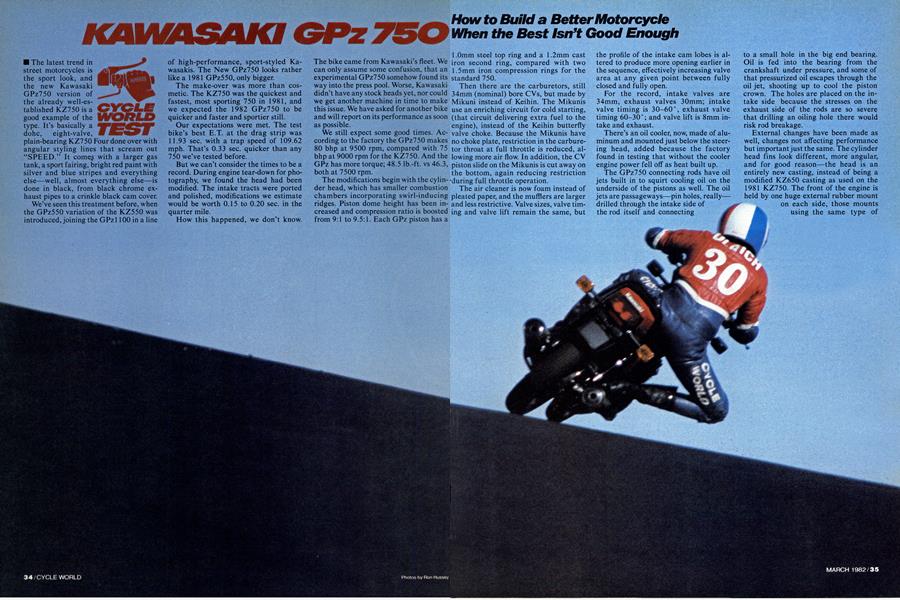

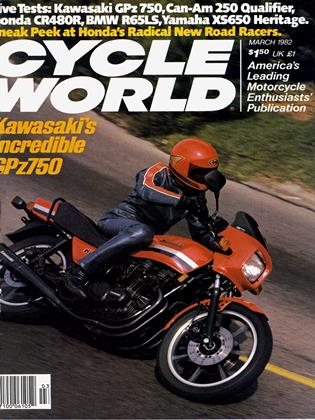

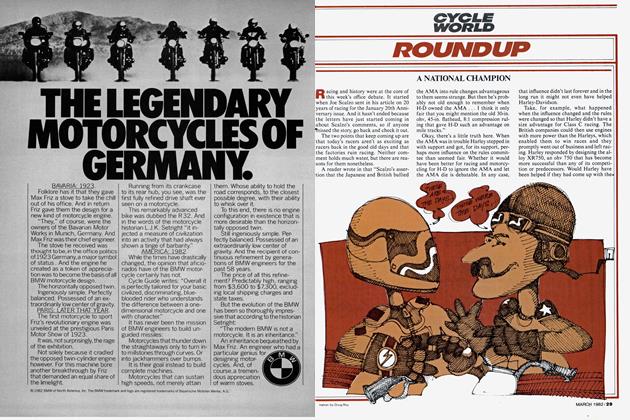

The latest trend in street motorcycles is the sport look, and the new Kawasaki GPz750 version of the already well-established KZ750 is a good example of the type. It’s basically a dohc, eight-valve, plain-bearing KZ750 Four done over with angular styling lines that scream out “SPEED.” It comes with a larger gas tank, a sport fairing, bright red paint with silver and blue stripes and everything else—well, almost everything else—is done in black, from black chrome exhaust pipes to a crinkle black cam cover.

We’ve seen this treatment before, when the GPz550 variation of the KZ550 was introduced, joining the GPzl 100 in a line of high-performance, sport-styled Kawasakis. The New GPz750 looks rather like a 1981 GPz550, only bigger.

The make-over was more than cosmetic. The KZ750 was the quickest and fastest, most sporting 750 in 1981, and we expected the 1982 GPz750 to be quicker and faster and sportier still.

Our expectations were met. The test bike’s best E.T. at the drag strip was 11.93 sec. with a trap speed of 109.62 mph. That’s 0.33 sec. quicker than any 750 we’ve tested before.

But we can’t consider the times to be a record. During engine tear-down for photography, we found the head had been modified. The intake tracts were ported and polished, modifications we estimate would be worth 0.15 to 0.20 sec. in the quarter mile.

How this happened, we don’t know. The bike came from Kawasaki’s fleet. We can only assume some confusion, that an experimental GPz750 somehow found its way into the press pool. Worse, Kawasaki didn’t have any stock heads yet, nor could we get another machine in time to make this issue. We have asked for another bike and will report on its performance as soon as possible.

We still expect some good times. According to the factory the GPz750 makes 80 bhp at 9500 rpm, compared with 75 bhp at 9000 rpm for the KZ750. And the GPz has more torque; 48.5 lb.-ft. vs 46.3, both at 7500 rpm.

The modifications begin with the cylinder head, which has smaller combustion chambers incorporating swirl-inducing ridges. Piston dome height has been increased and compression ratio is boosted from 9:1 to 9.5:1. Each GPz piston has a 1.0mm steel top ring and a 1.2mm cast iron second ring, compared with two 1.5mm iron compression rings for the standard 750.

How to Build a Better motorcycle When the Best Isn’t Good Enough

Then there are the carburetors, still 34mm (nominal) bore CVs, but made by Mikuni instead of Keihin. The Mikunis use an enriching circuit for cold starting, (that circuit delivering extra fuel to the engine), instead of the Keihin butterfly valve choke. Because the Mikunis have no choke plate, restriction in the carburetor throat at full throttle is reduced, allowing more air flow. In addition, the CV piston slide on the Mikunis is cut away on the bottom, again reducing restriction •during full throttle operation.

The air cleaner is now foam instead of pleated paper, and the mufflers are larger and less restrictive. Valve sizes, valve timing and valve lift remain the same, but

the profile of the intake cam lobes is altered to produce more opening earlier in the sequence, effectively increasing valve area at any given point between fully closed and fully open.

For the record, intake valves are 34mm, exhaust valves 30mm; intake valve timing is 30-60°, exhaust valve timing 60-30°; and valve lift is 8mm intake and exhaust.

There’s an oil cooler, now, made of aluminum and mounted just below the steering head, added because the factory found in testing that without the cooler engine power fell off as heat built up.

The GPz750 connecting rods have oil jets built in to squirt cooling oil on the underside of the pistons as well. The oil jets are passageways—pin holes, really— drilled through the intake side of the rod itself and connecting jjf

to a small hole in the big end bearing. Oil is fed into the bearing from the crankshaft under pressure, and some of that pressurized oil escapes through the oil jet, shooting up to cool the piston crown. The holes are placed on the intake side because the stresses on the exhaust side of the rods are so severe that drilling an oiling hole there would risk rod breakage.

External changes have been made as well, changes not affecting performance but important just the same. The cylinder head fins look different, more angular, and for good reason—the head is an entirely new casting, instead of being a modified KZ650 casting as used on the 1981 KZ750. The front of the engine is held by one huge external rubber mount on each side, those mounts

Ak using the same type of rubber pieces as the GPzl 100/KZ 1000J engines without requiring changes to the KZ750 crankcase casting (The KZ750 has two setsof rigid front engine mounts). The GPz750’s rear engine mount is rigid, as it is on the larger Kawasakis, to maintain the relationship between the countershaft sprocket and the swing arm pivot, necessary for long chain life. To keep the frame rigid without the bracing effect of a solidly - mounted engine, a crosstube is welded between the frame downtubes just below the engine’s rubber mounts.

At 57.25 in. the KZ750’s wheelbase is short for the class, which made it steer easily and turn quickly, too quickly for some riders. The GPz’s wheelbase is 58 in., with the extra length added to the swing arm. The steering head angle of 27° is the same, which adds up to steering that’s a fraction slower, just as precise and perfectly stable in a straight line.

And when they lengthened the swing arm, Kawasaki engineers extended the gussets aft of the pivot, which makes it less likely to flex.

Steering head bearings are tapered rollers vs. the KZ’s ball bearings. The upper triple clamp is changed, too, and missing are the usual handlebar clamps. That’s because the GPz750 has forsaken conventional steel tube handlebars for forged aluminum bars. I-beam risers clamp around the fork tubes above the upper triple clamp, and solid bars clamp into the I-beams.

The result is handlebars that are flatter but have almost normal rise, bars that look racy and work without the arm and wrist agonies caused by clip-ons or the lower back pain induced by pullbacks. Not only do the GPz bars work for the racer careening around corners, but for the street rider cruising to the store as well. The combined weight of the new bars and upper triple clamp is 0.9 lb. less than the combined weight of 1981 KZ750 handlebars and upper triple clamp.

The forks have less travel, 5.9 in. vs. 6.3 in. a change accomplished by inserting a small top-out spring in each leg. Kawasaki engineers said the change was designed to reduce the tendency to topout and wheelie under hard acceleration.

Those same forks are still air-assisted, with a suggested pressure setting of 10 psi, but now the legs are linked through an O-ring sealed passageway in the lower triple clamp, and air is added through a valve on the right side of that triple clamp.

At the same time that fork travel was reduced, rear wheel travel was increased, from 3.7 in. on the KZ750 to 4.4 in. on the GPz750.

Making the seat base out of plastic instead of steel and the rear brake pedal out of forged aluminum instead of tubular steel reduced weight, as did eliminating the second set of front motor mounts, making the front master cylinder more compact, and replacing the conventional tach cable with a wire running to the new electronic tachometer. But fitting the GPz750 with its sport fairing and rectangular headlight and oil cooler and dual horns (vs. the KZ750’s single horn) and new instruments (including LCD fuel gauge and sidestand warning light and battery fluid level warning light) and fork air pressure equalizer tube and rubber engine mounts and new frame bracing to accommodate those mounts and larger mufflers and longer swing arm and a new, larger gas tank (holding 5.7 gal. to the KZ’s 4.6 gal.) all added weight. That the GPz750 weighs just 15 lb. more than the KZ750 with half a tank of gas (506 lb. vs. the KZ’s 491 lb.) is somewhat of a technical miracle.

Despite the current fascination with electronic and automatic everythings, the GPz750’s instrument panel is new and technical . . . and restrained. There’s a warning light to tell the rider when fuel level is reaching reserve, or when the sidestand is down, or that the battery needs water. But it’s a small light and it informs without interfering. The tachometer contains a voltmeter: push the button and the tach needle moves to a scale in the center of the dial and tells you the battery’s voltage, i.e. state of charge. The fuel gauge is a stack of small LCD squares, nine in all. As fuel level drops, the squares empty. When only two remain, the modest warning light comes on.

The horns are loud and the turn signals are rider controlled, that is, non-automated. Without getting into that debate, it’s fair to comment that lack of automation seems to fit a sports bike.

So does the quartz-halogen headlight, although the fairing makes adjustment difficult, and the instruments are easy to read in sunlight and at night. We would have liked longer stalks for the mirrors, as they sat low enough for the rider’s sleeves to partially block the view to the rear. Not all riders liked the control pod on the left bar, because the turn signal switch was a reach for some and the fourway flasher seemed too automotive. The rocker switch for the horn fell readily to thumb, as they say.

The simplicity of a carb-mounted choke control vs the convenience of the bar-mount is another fair debate. The GPz’s is on the carb, and worked well.

The choke has three distinct positions, being off, full on and about half-on. With the choke (or, more correctly, the enrichening circuit) full on, the GPz750 starts quickly in cold weather and settles into a slightly-faster-than-normal (1500 rpm) idle. It can then be ridden away, but the rider must be careful not to use the brakes too hard before the engine warms up, because doing so will flood the engine and cause it to die. If the rider prefers to let the bike warm up in the driveway, a few minutes after starting the fast idle turns into a 3000-4000 rpm roar and the choke can be clicked back to half-on. A few miles later the choke can be turned off and forgotten.

Unless it is cold or raining. On cold mornings, the bike demanded half choke for at least a dozen miles, and on one cold and rainy night it covered 35 freeway miles at 60 mph and still refused to carbúrate normally without half choke.

That’s unusual, and may be related to the cylinder head porting and polishing mentioned earlier, since smoother intake ports don’t do as good a job of atomizing fuel when the engine is anything but blazing hot.

The carburetors, which flow more air and improve top-end horsepower, have a flat spot that shows up at high rpm when the rider goes from full throttle to no throttle and back again. The hesitation is momentary, usually occurring when it’s time to roll on the gas and steam out of a corner, the engine gasping for air and then kicking in again. It’s something the KZ750 didn’t do.

But both the above are minor glitches. There was no dissension regarding performance. Everybody who rode the GPz750 approved and the harder they rode, the more fervent the approval. Once again Kawasaki has taken the classic, basic approach to high performance. The lightweight engine—remember, it’s a 750 built from a 650—was given more compression and more mid-range camshaft timing, which added power to the lower and center parts of the dial. Then the lowrestriction carbs let the engine flow more air, so it breathes better at high revs, moving the power peak up and adding to total power. The extra 5 bhp are an addition rather than a relocation.

Once again, it’s a shame we can’t report stock figures. The KZ750 came off corners harder than its class rivals in 1981 and the GPz750 has even more of a charge. We wouldn’t be surprised to see the 750 do to box stock racing what the GPz550 has already done, that is, clean up.

By the book, the GPz750’s suspension is as basic as the engine. And in use, it’s just as effective.

There is no race-derived single rear shock, no anti-dive front suspension. Instead the forks have air assist and the rear shocks come with a choice of six preload settings and five choices of rebound damping, adjusted by turning a collar on the shock body. Damping increases by about 20 percent with each click of the control, and the No. 5 position offers approximately twice the resistance of No. 1.

Through trial and error we found the suspension worked well at speed with 25 psi in the forks, No. 5 (maximum) damping for the shocks and No. 3 (of six) on the rear spring preload.

Because this all ties together, there should be a special mention for the tires. Our test bike came with Dunlops, 100/90-19 F8 Mk. II in front, a 120/90-18 K427 in the rear. These are tubeless tires, they are designated OE, that is, built to be sold to the factory and delivered on production bikes.

And they were terrific. Better than any Japanese OE tires we could remember. We’d heard about Dunlop’s Elite series, the DOT-legal stickies seen mostly in box-stock racing, but this Mk. II and K427 stuff was news.

Dunlop calls them second-generation OE tires. Three or four years ago the big factories began cranking out fast motorcycles that also handled. It quickly became known, by riders and the press, that tires built to a price were adequate but no more, and that engines and suspensions were promising more than the tires could deliver. So the factories, Kawasaki in this case, arranged to have good tires built for their sporting models, better tires at a higher price.

Next, hardware. As some of us learn the hard way, when you lean a motorcycle far enough, things scrape. Fact. Can’t be

helped, not unless you have tires that slide before there’s much lean, or unless you’re on a dresser with floorboards.

What touches, or perhaps where the touch-down point is located within the wheelbase, is vital. In the GPz750’s case, first come the folding footpegs, then the centerstand tab on the left and the exhaust pipe on the right.

These touchdown points are toward the rear.

Okay. As they say after the thrill shows, kids, don’t try this at home. This is racetrack business and we don’t like letters from guys who’ve crashed riding too fast.

But. If the bike does scrape hard enough to lever itself, the rear wheel will slide. This can be corrected. If the rider

sits up and closes the throttle the GPz snaps upright, the rear tire comes back down and the rider continues on his way, rubber sid-e down. That’s good. It means the motorcycle is forgiving.

Back to the suspension. With the settings mentioned above and with the tires inflated to 32 psi in front, 35 psi in back, the GPz750 inspired total confidence. The extra wheelbase gives neutral steering, that is, the bike goes where it’s pointed and reacts as fast as the rider’s input; no darting sooner or further than expected. There’s plenty of ground clearance, and the tires are so good they aren’t at their limits when things strike sparks and when that happens, less enthusiasm will save the day.

Confidence.

This extends even to the controls. We seldom let an issue pass without carping about how the pullback bars so popular elsewhere make fast riding difficult. We seldom admit to the opposite, that the clip-ons and ace bars of the cafe crowd are just as demanding in a different way, that being that low and that narrow makes it damned difficult to climb off a road bike and onto the road racer and ride with any degree of control. But the GPz’s bars are just where they should be, low enough and high enough at the same time.

We never did find the sporting limit of the tires, while at normal pressures, on the highway they worked fine, even in the rain.

Our wild hair rider came back to the office, dialed the suspension down to full soft and the humdrum crowd reported the GPz’s ride was better than the average touring bike.

The brakes rated four out of five. They turned good numbers at the test track and held up well at racing speeds. Kawasaki engineers say the brake components, as in calipers, pads and leverage ratios, aren’t changed. We suspect the superior results on the track are due to the new dogleg levers: maximum power comes with the lever closer to the grip, making effort easier to modulate. The only complaint was that for some riders effort wasn’t linear enough, meaning that pulling twice as hard gave more than twice the braking.

Time to remind all parties that this isn’t a perfect motorcycle, or even a perfect sporting motorcycle. The tires are great, for original equipment, but the next grade up will be better. The shocks are great, for original equipment, but the aftermarket offers better control and longer life, admittedly at a price. And anti-dive forks and progressive-rate solo shocks can be at least as good and not need adjustment between fast and featherbed.

What we have here is an improved KZ750, already the best in its class. There’s more performance—despite the' unfortunate disqualification mentioned earlier—and the various changes in chassis, suspension, etc., make the GPz750 not just more sporting, but more useful. Riders who felt the ’81 KZ was a little too small liked the longer seat and lower bars as well as they did the slower steering. The GPz seems heavier at rest or being rolled around the garage, but once under way it feels like ... a Kawasaki; that distinctive sense of raw strength, muscular and unbreakable.

In sum, Kawasaki has done a good job of making a sporting bike more sporting without sacrificing comfort or streetpracticality.

The GPz750 is a nice piece of work.

KAWASAKI

GPz 750

$3349