Idol speculation

EDITORIAL

EVERYBODY LOVES A HERO. I GUESS that’s why we all have role models of some sort, people whom we try to emulate in the shaping of our own lives. In that respect, there’s no difference between grade-schoolers who idolize sports figures, teenagers who worship rock stars or middle-aged businessmen who revere famous executives; they all are living under the influence of heroes.

I’m no exception; I have my own list of heroes, extraordinary people of both sexes whom I find admirable and inspirational. I'm pretty fussy, though, when it comes to allowing anyone into that select group. Not that I’m snooty or have unreasonably high standards; it’s just that I don’t consider people heroes simply because they’re exceptionally good at their jobs. And that applies in particular to the superstars of motorcycle racing. If any of them are to make my list of heroes, they’ll have to do so for reasons other than their ability to work magic with a motorcycle.

Don't get me wrong; I have nothing but respect for the Eddie Lawsons and Ricky Johnsons and Bubba Shoberts of the world. Many times over the years, I’ve watched in awe as riders who possessed this highest order of talent turned the operation of a racebike into poetry in motion. I’ve been lucky enough to see many of the sport’s legends in action, to feel chills running up and down my spine while watching the likes of Kenny Roberts and Bob Hannah and Jay Springsteen defy the laws of physics.

But as far as I’m concerned, that’s what top professional racers are supposed to do. They’re paid to win. They’re paid to thrill. They’re paid to be the best there is. And I just can’t bring myself to consider someone a hero—by my definition of the word, at least—simply for excelling at the one thing at which he or she is paid handsomely to excel.

Rather, my heroes tend to be people who excel at something they’re not paid to do: being exemplary, inspirational human beings with exceptional strength of character.

Many of my heroes are sports luminaries past and present, but not just from the world of motorcycling. One of my favorites is Willie Stargell, a baseball Hall of Fame candidate who was a feared homerun hitter before retiring a few years ago. He earned a permanent spot in my hall of fame not for his ability to lose baseballs, but for his ability not to lose sight of reality, even under very stressful circumstances. He never forgot that his job was not to negotiate world peace or find a cure for cancer, but simply to hit the ball with the stick. Once, when asked how he was always able to stay so calm and collected, even in the face of bitter defeat, he just smiled and replied, “Listen to what the umpire says at the beginning of every game. He doesn’t say 'Work ball'; he says 'Plciv ball.’ We’re just big kids lucky enough to get paid an incredible amount of money for playing a little kid's game.”

An ability to maintain that same kind of equilibrium has made stockcar racing’s Richard Petty another of my heroes. Petty is unflappable, a class-act human being who never is publicly bitter about or critical of the hand fate deals him, even if a fellow driver mindlessly causes a crash that destroys Petty’s car. injures his body and costs him valuable championship points. Instead, Petty invariably climbs out of the smoking wreckage with a smile for the camera, a wave for his fans and a philosophical, “Well, that’s racing” outlook on the entire incident. Sure, he’s the winningest driver in stock-car racing history, but that has little bearing on my opinion of him as a magnificent role model for us all.

I feel the same way about Dick Mann. Although he arguably was the most versatile motorcycle racer ever. I admired him most of all for the courage and press-on-regardless tenacity he displayed during his years on the AMA circuit. Today, when I read about millionaire sports stars who are sidelined because of things like stubbed toes or upset stomachs,

I can't help but think about Dick Mann, who was not above sawing off a leg cast or duct-taping crushed fingers together just so his relentless pursuit of the Number One plate could continue uninterrupted. Even now, at age 53, Mann carries on in the same spirit, still racing motorcycles despite a body that has been hobbled by a lifetime of injuries.

Not all of my role models are such legendary figures as Mann and Petty, however. I'll bet, for instance, you've never heard of Reinhard Knoll, an-

p .....

other of my heroes. Riding in the 1976 ISDT held in his native Austria, Knoll crashed big-time on the morning of Day Five, mangling his left hand so badly it was rendered useless. But he finished the event anyway, riding the remaining two days in excruciating pain while one-handedly negotiating terrain that was difficult for riders with two hands. A courageous man, indeed.

That goes double for Dick Miller, former Editorial Director of MOTOCROSS ACTION magazine and accomplished off-road racer of the Seventies. While pre-running the Baja 1000 about 10 years ago. Miller was hit head-on by a pickup in a desolate area of Baja and left for dead by the truck’s driver. Despite injuries that would have instantly killed a lot of people, Miller somehow survived more than eight hours of pain, exposure and blood loss as he lay alone and helpless on his back atop his shattered leg. And after finally being found by his riding companions, he had to endure yet another hours-long wait for a Med-Evac helicopter to arrive and rush him to a military hospital in the States. The doctors who treated him said they had never before encountered anyone with such an iron-willed desire to live, for by all rights, he should have died within a few hours of the accident. But Miller refuse to succumb, and lived to ride again another day.

That’s my idea of courage-and my definition of a hero. —Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

At Large

At LargeService Bulletins

December 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsDesmo Fever

December 1987 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1987 -

Roundup

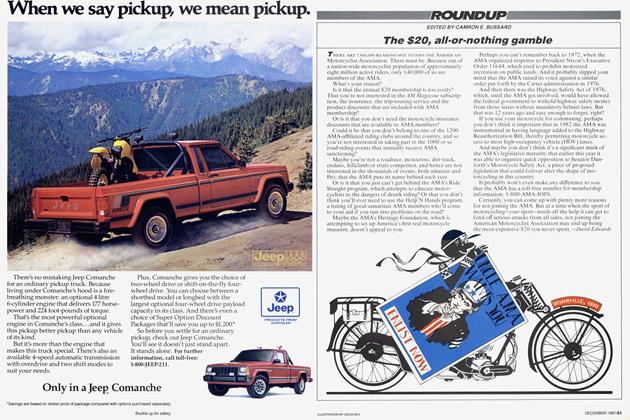

RoundupThe $20, All-Or-Nothing Gamble

December 1987 By David Edwards -

Roundup

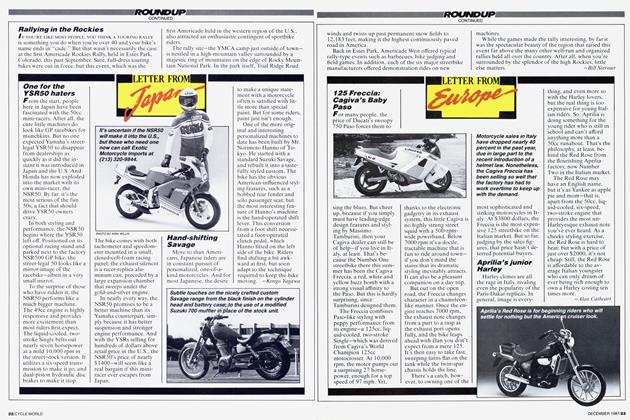

RoundupRallying In the Rockies

December 1987 By Bill Stermer -

Roundup

RoundupOne For the Ysr50 Haters

December 1987