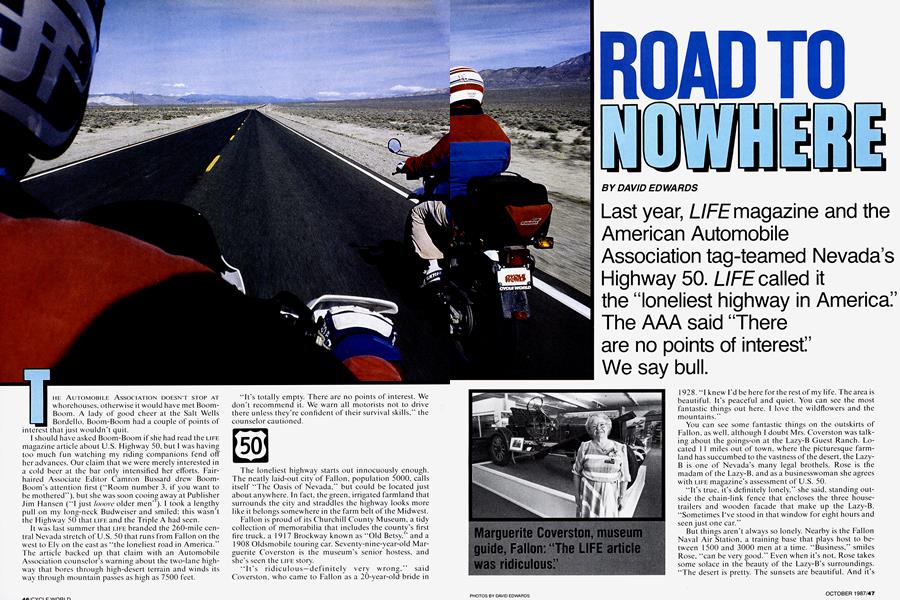

THE AUTOMOBILE ASSOCIATION DOESN'T STOP AT whorehouses, otherwise it would have met Boom-Boom. A lady of good cheer at the Salt Wells Bordello, Boom-Boom had a couple of points of interest that just wouldn’t quit.

I should have asked Boom-Boom if she had read the LIFE magazine article about U.S. Highway 50, but I was having too much fun watching my riding companions fend off her advances. Our claim that we were merely interested in a cold beer at the bar only intensified her efforts. Fairhaired Associate Editor Camron Bussard drew Boom-Boom's attention first (“Room number 3, if you want to be mothered"), but she was soon cooing away at Publisher Jim Hansen (“I just hoove older men"). I took a lengthy pull on my long-neck Budweiser and smiled; this wasn’t the Highway 50 that LIFE and the Triple A had seen.

It was last summer that LIFE branded the 260-mile central Nevada stretch of U.S. 50 that runs from Fallon on the west to Ely on the east as “the loneliest road in America." The article backed up that claim with an Automobile Association counselor’s warning about the two-lane highway that bores through high-desert terrain and winds its way through mountain passes as high as 7500 feet.

“It’s totally empty. There are no points of interest. We don’t recommend it. We warn all motorists not to drive there unless they're confident of their survival skills," the counselor cautioned.

50

The loneliest highway starts out innocuously enough. The neatly laid-out city of Fallon, population 5000, calls itself “The Oasis of Nevada," but could be located just about anywhere. In fact, the green, irrigated farmland that surrounds the city and straddles the highway looks more like it belongs somewhere in the farm belt of the Midwest.

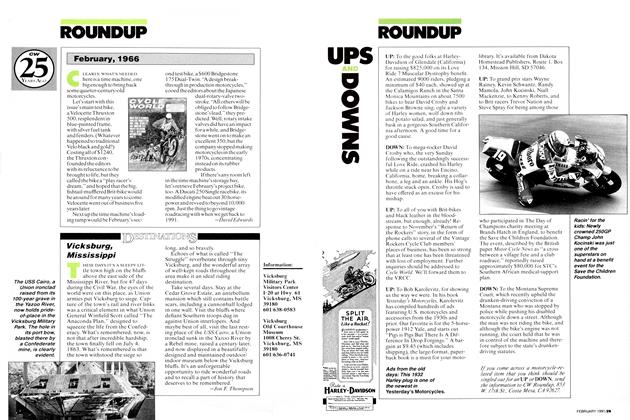

Fallon is proud of its Churchill County Museum, a tidy collection of memorabilia that includes the county’s first fire truck, a 1 91 7 Brockway known as “Old Betsy," and a 1908 Oldsmobile touringcar. Seventy-nine-year-old Marguerite Coverston is the museum’s senior hostess, and she’s seen the LIFE story.

“It’s ridiculous —definitely very wrong,’’ said Coverston, who came to Fallon as a 20-year-old-bride in 1928. “I knew I’d be here for the rest of my life. The area is beautiful. It’s peaceful and quiet. You can see the most fantastic things out here. I love the wildflowers and the mountains.”

ROAD TO NOWHERE

DAVID EDWARDS

Last year, LIFE magazine and the American Automobile Association tag-teamed Nevada's Highway 50. LIFE called it the "loneliest highway in America." The AAA said "There are no points of interest." We say bull.

You can see some fantastic things on the outskirts of Fallon, as well, although I doubt Mrs. Coverston was talking about the goings-on at the Lazy-B Guest Ranch. Located II miles out of town, where the picturesque farmland has succumbed to the vastness of the desert, the LazyB is one of Nevada’s many legal brothels. Rose is the madam of the Lazy-B, and as a businesswoman she agrees with LIFE magazine’s assessment of U.S. 50.

“It’s true, it’s definitely lonely,” she said, standing outside the chain-link fence that encloses the three housetrailers and wooden facade that make up the Lazy-B. “Sometimes I’ve stood in that window for eight hours and seen just one car.”

But things aren’t always so lonely. Nearby is the Fallon Naval Air Station, a training base that plays host to between 1500 and 3000 men at a time. “Business,” smiles Rose, “can be very good.” Even when it’s not. Rose takes some solace in the beauty of the Lazy-B’s surroundings. “The desert is pretty. The sunsets are beautiful. And it’s deathly quiet; sometimes you can almost hear forever,” she says.

NOWWHERE

At other times on Highway 50 it seems as if you can see forever. It’s 1 10 miles from Fallon to Austin, with just one gas station in between, and most of the road is as straight as the crease in a Marine’s dress blues. Brake to a stop in one of the shallow valleys that the highway bisects, switch off the engine and you are confronted with the most amazing panorama. The road stretches out east and west for what could easily be a thousand miles. The sky is an immense, blue canopy, dotted with clouds that stand out in 3-D relief. On the horizon, a ring of jagged, brown mountains frames the whole scene.

David Jenkins had a lot of time to contemplate that scenery. Jenkins, 39, was a hitchhiker in the 1960s, and now does the same thing but calls himself a “road person.”

Thirty miles out of Fallon, on his way from Seattle to North Carolina, Jenkins wasn’t having much luck in shagging a ride. “In the late Sixties, this trip took two to three days, but now it’s two to three weeks,” Jenkins shrugged. Still he didn’t seem to mind.

“I like it out here,” he said as yet another car ignored his upturned thumb. “It’s nice and peaceful. Yeah, it might be the loneliest road in America, but sometimes that’s an advantage; sometimes that’s exactly what you need.”

Martin Jackson, also a Seattle resident, but one with a slightly more speedy mode of transportation, had good things to say about the solitude of U.S. 50, too. In the midst of a 5000-mile “break-in run” on his new Honda Gold Wing, Jackson had merrily eschewed the more mundane travel available on Interstate 80, 100 miles to the north. “I always avoid interstates and metropolitan areas when I’m touring. The backroads are a lot more beautiful, and you can relax more. I’ll tell you, though, right-now I’m wishing for a Hurricane 1000,” Jackson laughed, sighting along the shimmering asphalt that reached out for the mountains in the distance.

50

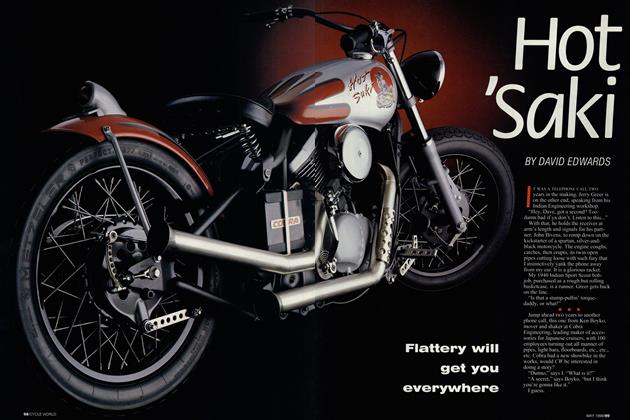

The perfect motorcycle for Highway 50 is neither a feature-filled touring bike nor a wind-racing sportbike. Instead, that honor goes to a type of machine a few pegs down on motorcycling's evolutionary scale, the dual-purpose bike. So for our trek across the loneliest highway, we chose a Honda XL600R, a Yamaha XT600 and a Kawasaki KLR650.

Having off-road capabilities is helpful if you’re in search of those elusive points of interest that the AAA had such a hard time finding. There are turn-offs to ghost towns, abandoned mining camps and archeological sites all along the highway. Just outside Fallon, there’s even a little slice of the Sahara, a 600-foot-high dune system called Sand Mountain. Most of these attractions are accessible by road bike, car or even motorhome, but no streetlegal vehicle will come close to a dual-purpose bike when a smoothly graded dirt road peters out to a narrow, bumpy cow trail.

NEVADA

Las Vegas

That’s how we found F-14 Hill.

From the highway it looked close. Two miles of puckerbush-dodging later, we were atop a rocky knoll overlooking a dry lake bed. The vista spread out before us was impressive, but nothing compared to what was about to happen a few hundred feet above our heads. What had been a pastoral afternoon sky was suddenly beseiged by the streaks and shrieks of a flight of F-14 Tomcats in mock dogfight. The boys at NAS Fallon sure know how to put on a show.

In the kind of tough slogging it took to get to F-14 Hill, the Honda was at its best. The XL600R simply has more dirt bike in it than do the other two machines; it feels lighter and more responsive, and it’ll wheelie the knickers clean off the KLR and XT. Unplug its lights and turnsignals, lever on a set of knobbies, and the XL probably wouldn't lose too many points in a local enduro.

The XT600 Yamaha, largely unchanged since its introduction in 1984, takes the traditional approach to dualpurpose riding, striving for a 50/50 compromise in its on/ off-road abilities. This means it won’t hang with the Honda during dirt excursions, but tends to be more comfortable out on the open road.

The Kawasaki takes a different tack: While it provides enough off-road competence to get by, it’s far happier on the road. Styled after long-distance rally bikes, the KLR650 has a six-gallon fuel tank (twice the capacity of the XL and XT), which gives great peace of mind when the nearest gas station is two counties away. The bike’s minifairing and handguards make highway cruising less tiring, although we ended up removing the small, dark-tinted windshield because it set up an annoying turbulence at helmet level. The KLR also has an electric starter, and thumbing its liquid-cooled engine to life was a far more pleasant experience than going through the kick-and-pant routines that sometimes afflicted the riders of the Honda and Yamaha. As a device for Highway 50 exploration, the KLR650 has a lot going for it.

NOWWHERE

50

Austin comes as a relief. The former mining boom-town was built along Pony Canyon, which forces Highway 50 into its first serious curves for more than 100 miles. In 1865, some 5000 people lived in Austin, brought there by dreams of a strike in the silver mines. Now a mere 600

residents keep Austin alive, and the owners of the shops, restaurants, hotels and filling stations that line Austin’s two-mile run of Highway 50 were none too happy with the prospect of the LIFE article scaring travelers—and their wallets—away.

Enter the quick-thinking Nevada Commission on Tourism (Capitol Complex, Carson City, NV 89710). The commission, along with the civic and business leaders of the towns along the route, came up with the “Highway 50 Survival Kit.” The kit includes a Nevada state map, a list of attractions, services and facilities, and a stylized Highway 50 map that can be stamped at places of business and tourist centers in each of the towns. A completed map earns its owner an “I Survived Highway 50” certificate signed by the governor. The state is even installing road signs officially proclaiming Highway 50 as The Loneliest Road.

“What we’ve done is turn lemons into lemonade,” said Bert Lewis, the president of Austin’s Chamber of Commerce. “Since we started the program, we’ve had increased traffic and more people stopping in town.”

Lewis came to Austin in 1978 with her husband, a Bureau of Land Management official, and didn’t take long to adapt to the Highway 50 lifestyle. “You don’t see any facades down here,” she said, pointing through her office window to a row of 100-year-old brick buildings. “This is real, just the way it was.”

In response to LIFE’S “loneliest highway” charge, she said: “I suppose you could say that 50 is more challenging than a four-lane interstate, but it’s a lot more entertaining. There’s constant change as you cross the valleys and mountain ranges. There are more points of interest than I can name; there’s always something to look for. We have a variety of plant life, there are historical and archeological sites, and as far as wildlife is concerned, you can see antelope, deer and wild horses from the highway.”

Austin gas station owner Joe Ramos is the kind of guy who’ll fix a fiat tire on your Kawasaki KLR650 and then matter-of-factly refuse payment for the chore. He raised his worn baseball cap and scratched his head when told that the AAA has suggested that Highway 50 travelers bone-up on their survival skills.

“Oh, every once in a while we’ll have somebody who runs out of gas. People aren’t used to 100 miles between gas stops. Sometimes it gets 'em in a pinch. But most people have more good than bad to say about the road. They like the scenery, and can make pretty good time,” he said.

Seventy miles to the east. Bill Tilton makes sure that you don’t make too good time, at least not in the town of Eureka, where he’s a Sheriff’s Department sergeant. He’ll allow you a few clicks over the town’s 25-mph limit, but don’t press your luck.

Anyway, it would be a shame to rip through Eureka. The town, population 450, has made the transition into the 20th century with a little more grace than has Austin, which is a trifle rough around the edges. During the mining heyday. Eureka was the second-largest city in Nevada, with almost 10,000 hardy souls hoping to get rich quick. Today the county courthouse and the opera house, along with several hotels, have been nicely restored. And there’s talk about resurrecting at least part of the town's underground tunnel system, which was used for delivering beer in the winter, and by the Chinese miners as opium dens.

If you like nosing around cemeteries and reading epitaphs on tombstones, Eureka is just the place. There are cemeteries for each major religion, as well as a posh final

resting place for those fortunate enough to have had money, and a less-well-kept burial ground for those unfortunate enough to have died from contagious diseases. The dead outnumber the living in Eureka by a wide margin.

Sgt. Tilton found the Triple A’s warnings about the highway that runs past the restored buildings and graveyards of Eureka a bit overstated. “If you do break down, somebody will inform the authorities about it in the next town. Personally, I like the road. I’d much rather travel 50 than 1-80; it’s just more scenic. And I’d definitely take 50 if I was on a motorcycle,” he said.

50

The loneliest highway in America ends in Ely, population 4500. Ely is a nice enough place, with all the convenience-store, fast-food trappings of a modern small town, but, unfortunately, none of the boom-town charm of Austin or Eureka, LIFE and the AAA were probably glad to get to Ely. Bussard, Hansen and I enjoyed a good dinner at the Jailhouse Restaurant and spent the evening drinking free whiskey and trading money with a nice lady behind a blackjack table. In the morning we got on the bikes and and gladly pointed their noses back towards Fallon.

As two-time survivors of the Highway 50 crossing, we’ve got some suggestions for LIFE magazine and the Triple A:

1 ) If you make the trip again, stop worrying about the lousy radio reception. Get out of the car and engage the locals in some good, old-fashioned conversation. Amazingly, they don’t bite.

2) Dust off your sense of curiosity and make sure you pack it along. Believe us, this “no points of interest” stuff is all in your minds.

3) You should have known this: To really make an adventure out of Highway 50, to fully savor its beauty and solitude, do it on a motorcycle, preferably a dual-purpose model, although any old two-wheeler will do just fine. Give yourself two days.

4) And say hi to Boom-Boom for us. ®

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialOh, Why, Tell Me Why

October 1987 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeSherlock And the Golden Hour

October 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1987 -

Roundup

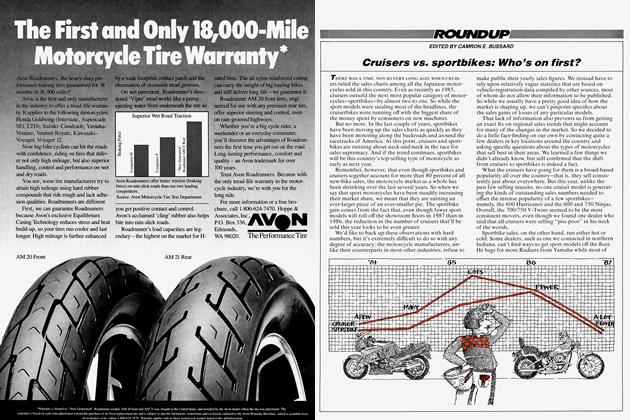

RoundupCruisers Vs. Sportbikes: Who's On First?

October 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Sdr Rocket

October 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia's Expansion Plans

October 1987 By Alan Cathcart