A crash course in career counseling

EDITORIAL

"WELL DOES THIS MEAN YOU'RE GOing to stop playing around with those dangerous motorbikes?"

I long ago lost count of how many times I've been asked that question in one form or another. Invariably, it's been posed by someone of the medical persuasion, a doctor or nurse or physical therapist who was doing his or her part to glue me back together after a motorcycle get-off. And although I know that those angels of mercy had good intentions, it’s not the counseling I’ve minded so much as the patronizing tone of voice and the icy, won’t-you-idiots-ever-learn stares that generally accompany it.

Now, please understand that I’m not a compulsive crasher; it’s just that in close to a million miles of piloting all kinds of motorcycles—including 14 years of testing, more than 20 years of racing and over 30 years of all-around pleasure riding—I've been presented with an astronomically high number of opportunities to bail off. Realistically, there was no way I could have avoided all of them. So while the list of motorcycle-related injuries I’ve compiled thus far seems rather extensive, I still have about a .999 batting average; and I’m particularly pleased that all of my OEM parts are still attached and in good working order.

But there’s no doubt that I’ve become intimate with more than my share of emergency rooms and doctor’s offices over the years. There’s also no question that I’ve grown weary of the unsolicited career counseling offered by the medical community. Once, in fact, when I pleaded with my family doctor to get my broken wrist back in working order pronto because I couldn’t do my job without it, he simply told me to find another line of work.

I had a better idea: I found another family doctor.

They just don’t understand, do they?

Oh, they know that we motorcyclists are somehow different, but they don’t quite know how and why. Sometimes they think we’re impervious to pain or have some kind of death wish, other times they conclude that we simply aren't bright enough to look after our own well-

being. Admittedly, any or all of those things could be said of some riders, but it's absolutely not true about the vast majority of us. All that biker death-wish business is pure horse puckey, and motorcycle riders are no more or no less capable of taking care of themselves than anyone else. And pain? Hey, we feel it just like everyone else does. The difference is in how we react to it.

Hard-core motorcyclists, you see, seem to have a slightly different program burned into their mental microchips. The result is a cause-andeffect logic that is highly atypical when it comes to the interpretation of pain.

No matter who you are, the logical reaction to pain is to avoid its cause. And when casual, uncommitted riders fall down and get hurt, they perceive the motorcycle as the cause of the pain; therefore, riding motorcycles must be avoided in the future. But to devoted motorcyclists who end up in plaster city, the crash is what caused the pain, not the bike, so it’s crashing that must be avoided. Rather than swearing off motorcycles forever, then, these riders react by figuring out what went wrong, and making the necessary adjustments in their riding techniques to insure that such a thing won’t happen again. “Let’s see, next time maybe I should take those jumps one at a time . .

I know all of this, of course, and so do most of you, especially if you’ve done enough racing or aggressive offroad riding to have bailed off quite a few times. But the medicos do not. So, being the type of people they

are—and believe me, I thank God they’re that way—their instinctive reaction is to chide us for being so immature as to get involved with motorcycles in the first place, and suggest that we come to our senses and give it up before it’s too late.

What I find curious about all this is that—to the medical profession, as well as to most non-motorcyclists— not all broken limbs are equal. If you snap a fibula or fracture a humerus while participating in one of the more socially acceptable sports, say, skiing or horseback riding, you're given the cheerful assurance by the doctors and nurses that “you'll be back in the saddle/on the slopes in no time.” And when you’re finally wheeled out the door and sent home, you wear your new cast like a badge of courage.

But when a motorcycle accident is the reason you’re being wrapped in plaster, the ambience is altogether different. The doctors and nurses shake their heads and cluck their tongues in disbelief, and—if anything—try to discourage you from climbing back aboard your twowheeled bucking bronco. No badge of courage here; on a motorcycle rider, a cast is more like a symbol of stupidity.

Actually, not all medical types treat injured motorcyclists in this fashion. I have, on rare occasion, encountered a doctor or a nurse who was reasonably sympathetic and very supportive of my fervent desire to get back on motorcycles as soon as humanly possible. And let’s face it—we all know that there are quite a few motorcycle riders who really should “hang it up” after a crash, either because their injuries are extensive enough to make any future riding a life-threatening proposition, or because they simply have proven to be such unsafe, crash-prone riders that they pose a hazard to themselves and everyone around them.

But the rest of us? Well, I guess we’ll just go on cluttering up outpatient wards from coast to coast, baffling the hired help and hoping they won’t berate us for being so mindless as to ride motorcycles—and wondering if we really should use a little more front brake next time in Turn Two.

Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

At Large

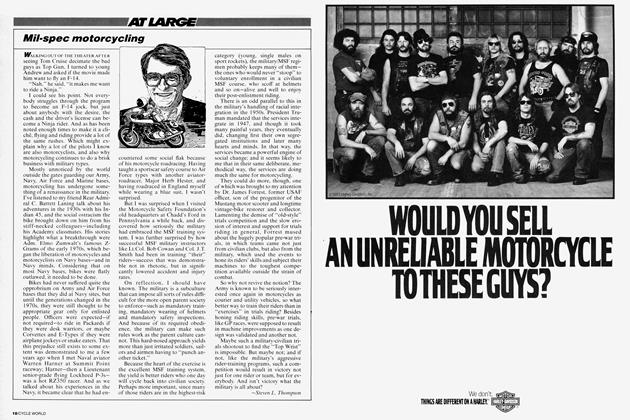

At LargeMil-Spec Motorcycling

June 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Shape of Things To Come

June 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

June 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

June 1987 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

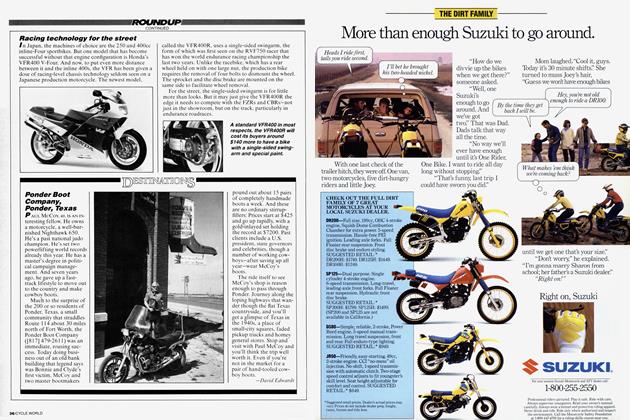

RoundupPonder Boot Company, Ponder, Texas

June 1987 By David Edwards