American Style in France and Finland

AT LARGE

THE BALANCE SHEET ON AMERICANEuropean trade, style-wise, is still seriously tilted in Europe’s favor. If your exposure to Europe consists of some package tours and a quick flip through whatever bike magazine happens to be in the local lingo, you’ll agree that Europeans don’t seem to be lining up at local bike shops to buy The American Look.

Okay. But what, exactly, is the American Look? Most obviously, there’s the cruiser/low-rider/Harley look, which certainly does have a presence in Europe, if not a major one. Then there is the Moto Cowboy look, typified by a battered dual-purpose bike, nowadays usually sporting a Paris-Dakar overlay. And that, you might imagine, is just about it—the cowboy and the low-rider. Period.

Wrong. A trend is emerging in Europe that’s ripe with irony and amusing to contemplate. It’s the trend toward American-style touring bikes. Every time I go to Europe, I see more and more evidence of it.

Take the summer evening I was in Rouen, France. I sat and sipped some potent red stuff in a small corner brasserie at about 10 o'clock, simply watching France stroll and roll past. A lot of the rollers did so on bikes, and, naturally, bistros like this one being a place where boy meets girl, a lot of the bikes were of the look-atme variety—snarling superbikes, in other words. The pattern of their arrival consisted of a high-speed stunt followed by a ferocious braking act to a halt, then a nonchalant kick of the sidestand and an insouciant stroll to a table, preferably one at which attractive young women strove without success to appear uninterested.

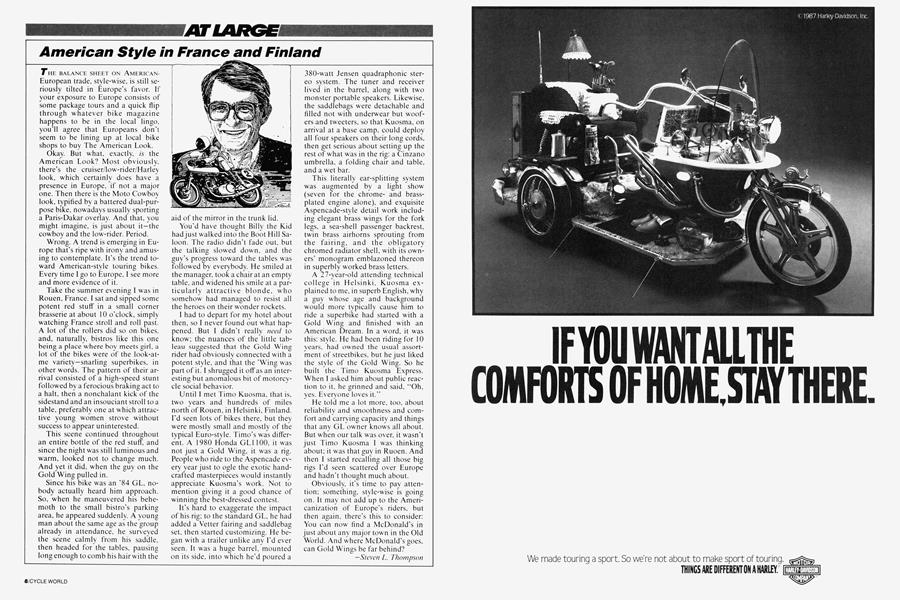

This scene continued throughout an entire bottle of the red stuff, and since the night was still luminous and warm, looked not to change much. And yet it did, when the guy on the Gold Wing pulled in.

Since his bike was an ’84 GL. nobody actually heard him approach. So, when he maneuvered his behemoth to the small bistro’s parking area, he appeared suddenly. A young man about the same age as the group already in attendance, he surveyed the scene calmly from his saddle, then headed for the tables, pausing long enough to comb his hair w ith the aid of the mirror in the trunk lid.

You'd have thought Billy the Kid hadjust walked into the Boot Hill Saloon. The radio didn't fade out, but the talking slowed down, and the guy’s progress toward the tables was followed by everybody. He smiled at the manager, took a chair at an empty table, and widened his smile at a particularly attractive blonde, who somehow' had managed to resist all the heroes on their wonder rockets.

I had to depart for my hotel about then, so I never found out w'hat happened. But I didn't really need to know; the nuances of the little tableau suggested that the Gold Wing rider had obviously connected with a potent style, and that the 'Wing was part of it. I shrugged it off as an interesting but anomalous bit of motorcycle social behavior.

Until I met Timo Kuosma, that is, two years and hundreds of miles north of Rouen, in Helsinki, Finland. I'd seen lots of bikes there, but they were mostly small and mostly of the typical Euro-style. Timo's was different. A 1980 Honda GL1 100, it was not just a Gold Wing, it was a rig. People who ride to the Aspencade every year just to ogle the exotic handcrafted masterpieces would instantly appreciate Kuosma’s work. Not to mention giving it a good chance of winning the best-dressed contest.

It’s hard to exaggerate the impact of his rig; to the standard GL. he had added a Vetter fairing and saddlebag set, then started customizing. He began with a trailer unlike any I'd ever seen. It was a huge barrel, mounted on its side, into which he'd poured a 380-watt Jensen quadraphonic stereo system. The tuner and receiver lived in the barrel, along with two monster portable speakers. Likewise, the saddlebags were detachable and filled not with underwear but woofers and tweeters, so that Kuosma, on arrival at a base camp, could deploy all four speakers on their long cords, then get serious about setting up the rest of what was in the rig: a Cinzano umbrella, a folding chair and table, and a wet bar.

This literally ear-splitting system was augmented by a light show (seven for the chromeand brassplated engine alone), and exquisite Aspencade-style detail work including elegant brass wings for the fork legs, a sea-shell passenger backrest, twin brass airhorns sprouting from the fairing, and the obligatory chromed radiator shell, with its owners’ monogram emblazoned thereon in superbly worked brass letters.

A 27-year-old attending technical college in Helsinki. Kuosma explained to me, in superb English, why a guy whose age and background would more typically cause him to ride a superbike had started with a Gold Wing and finished with an American Dream. In a word, it was this: style. He had been riding for 10 years, had owned the usual assortment of streetbikes, but he just liked the style of the Gold Wing. So he built the Timo Kuosma Express. When I asked him about public reaction to it, he grinned and said. “Oh, yes. Everyone loves it.”

He told me a lot more, too, about reliability and smoothness and comfort and carrying capacity and things that any GL owner knows all about. But when our talk was over, it wasn't just Timo Kuosma I was thinking about; it was that guy in Ruoen. And then I started recalling all those big rigs I'd seen scattered over Europe and hadn't thought much about.

Obviously, it’s time to pay attention; something, style-wise is going on. It may not add up to the Americanization of Europe's riders, but then again, there’s this to consider: You can now find a McDonald’s in just about any major town in the Old World. And where McDonald’s goes, can Gold Wings be far behind?

Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

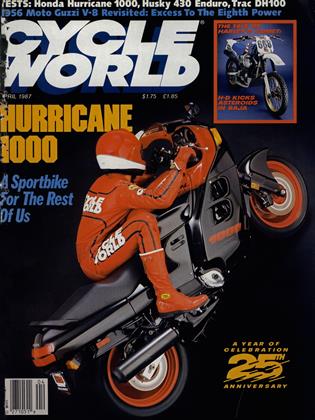

EditorialThe Best of Rides, the Worst of Bikes

April 1987 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupLending History A Helping Hand

April 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

April 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

April 1987 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupHood Bakery

April 1987 By Camron E. Bussard