THE 125 MOTOCROSSERS

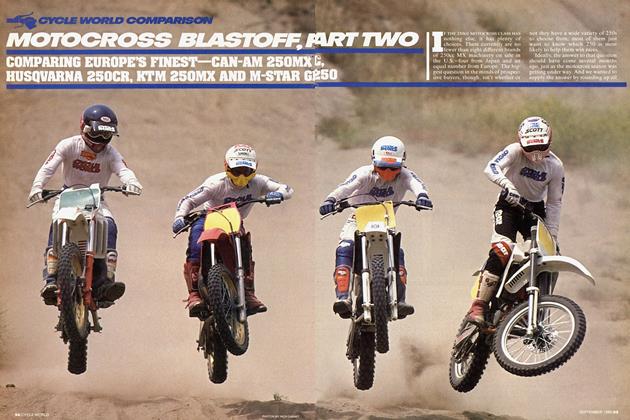

CYCLE WORLD COMPARISON

SUZUKI RM125 KTM 125MX KAWASAKI KX125 CAGIVA WMX125 YAMAHA YZ125 HONDA CR125

OVER THE PAST COUPLE OF years, picking the most competitive 125 motocross bike has been a fairly easy job. Kawasaki’s KX125 has been the most powerful and best handling bike in the class, and in stock form it was the one most likely to win. The KX has been so good that our test riders usually were able to detect its superiority early in the first day of testing.

Finding the winner of this 125 MX comparison wasn’t so easy. Not by a long shot. Three of the six bikes were still neck-and-neck at the close of the first day of testing on DeAnza’s demanding, rock-hard, hillside track. Only after three solid days of flogging by six riders on two different tracks was it possible to pick a winner. But it still wasn’t easy. The difference between the top three finishers is very small, and the fourth-place bike isn’t far off the mark at all.

Day Two found our test crew at Perris Raceway’s fully prepped and watered track. Big, loamy, bermed turns, a couple of double jumps, a long stutter-bump section, several high-speed straights and numerous pinnacle-type jumps all combine to make Perris an interesting and challenging motocross course. About 15 times a lap, Perris forces a bike to land on flat ground after being pitched into the air over short, steep > jumps. That’s quite demanding, for suspensions as well as for riders.

H1~1AVYDUTY WARFARE BETWEEN THE LIGHTWEIGHTS

HONDA CR125

WHAT HONDA WANTS. HONDA USUALLY GETS. That’s been true in everything from racing to marketing. But for years, Honda has been denied the honor of having the best 125cc motocrosser. Since 1975, the CR125 has been close, but never good enough.

This year marks Honda’s most serious effort. No, the CR125R is not all-new—last year’s bike was too good to be thrown away—but it is seriously refined, particularly in its front and rear suspension. The linkage on the Pro-Link rear system yields a more-progressive lever ratio, and the front fork now has positionsensitive compression damping.

In the engine, there’s a smaller, lighter barrel, along with changes in the porting, ignition timing, airbox and exhaust-pipe that are claimed to result in more horsepower. The bike still has an oval-slide Keihin carb and the Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber (ATAC), but the ATAC’s subchamber now is made of aluminum. The idea there, of course, is to reduce overall weight. Weight also has been pared from the radiators, the frame, the front axle and the front brake. And Honda’s ounce-scavenging efforts have paid off: At 192 pounds, the CR125R is the lightest 125 motocrosser available.

Dozens of detail refinements round out the new package, but there are no unnecessary changes on the CR. Honda’s new philosophy seems to be based on changing the bike to make it better, not changing it just to make it different.

Under those conditions, the Honda CR125R’s suspension proved the most comfortable and effective, yet it worked equally well when crossing smaller bumps at speed. Most testers, in fact, rated the CR’s fork above the others. The KX125 was a close second in the suspension department; the new Uni-Trak rear end is smooth and plush, but the fork is on the harsh side when landing from killer jumps, and the front wheel sometimes bounces back into the air after landing, indicating a lack of rebound damping. The YZ125 has much better suspension than past efforts from Yamaha, but it, too, has a few problems. The rear wheel tends to kick when braking on rough downhills, and the fork is mushy under some circumstances and harsh under others. The RM’s rear suspension behaves beautifully, but its fork is harsh and doesn’t feel like it is working in harmony with the rear.

The Cagiva and the KTM had suspension problems of their own, even though they both use quality fork and shock components. Both bikes have damping and spring rates calibrated for European preferences, with soft springs and heavy compression damping. Most American riders pre fer just the opposite—stiffer spn~ and softer compression damping. The KTM misses the mark the most. Its White Power shock has external damping-adjustment knobs, but their range is limited; the shock needs internal revalving. The KTM’s White Power fork can’t be externally adjusted, and only an experienced mechanic should attempt internal valving changes. In the past, we’ve had ^ood results with revalving of the up'"-down fork on KTMs. All of the right parts are there, but they’re in the wrong places for American tracks.

KAWASAKI KX125

IN REALITY, KAWASAKI DIDN’T HAVE TO DO A thing to its 125 motocrosser for 1986; the KX125 already was the best. But the KX has been changed more this year than it has in the last three years combined. Obviously, Kawasaki has made a serious effort to keep the KX125 on top.

The biggest change is in the rear suspension. Gone is the traditional Uni-Trak layout in which a large rocker arm under the seat compressed the shock. Instead, there’s a linkage mounted under the swingarm and a stationary mount at the top of the shock. The shock still features independently adjustable highland low-speed compression damping and rebound damping.

This new rear suspension allows the use of a removable rear-frame section like those Honda and KTM have been using for several years; the KX’s rear section, though, is aluminum. Also new for 1986 is the Kayaba front fork, which features position-sensitive compression damping, and a rear disc brake. The hydraulic caliper mounts directly on the swingarm, so the brake is not a full-floating unit.

There are no radical changes in the KX’s powerplant. It still uses a non-boreable Electrofusion cylinder, the Kawasaki Integrated Powervalve System (KIPS)—a kind of YPVS and ATAC combined—and a “Keyhole” Mikuni carb, so named because of its inverted egg-shaped venturi. Minor port changes are intended to give the KX more low-end power, but otherwise, the engine is still the same single-radiator trump-card that Kawasaki has used to stay on top of the 125 class for two years. With the effort Kawasaki has put into the rest of the machine, it’s clear that the company is aiming for three in a row.

The Cagiva’s Ohlins shock is fairly close on valving, but it’s hampered by a soft, heavily preloaded spring that makes the rear end misbehave when entering whooped turns. Still, the shock would be acceptable if the fork worked properly. We played with the adjuster knob on the lower right fork leg and experimented with oil levels and oil weight throughout the test, but never found a setting that felt right. Redrilling or replacing the Marzocchi damper rods will probably be necessary to make the fork competitive.

Steering characteristics also vary considerably on these bikes. They all steer well on high-speed straights and through sweeping turns. But when the course gets tight, the Honda emerges the clear winner, with the Cagiva, the Yamaha and the Kawasaki tied for second. Actually, with a fork that worked properly, the Cagiva would steer as well as the CR. The KTM, on the other hand, wants to turn but the suspension works against it on rough ground; the rider has to make too many corrections to stay on line, and the bike sometimes tries to climb the berm when exiting a turn.

YAMAHA YZ125

T’S NO SECRET THAT FOR YEARS, YAMAHA HASN'T been in the ballpark with its 125 motocross bikes. Everyone knows it, especially Yamaha. That explains why the YZ125 is a totally new machine for 1986, from the knobbies up.

Really, the engine’s 56mm-by-50mm bore-andstroke measurements are about all that this year’s YZ 125 has in common with last year’s. The layout of the engine’s internals has been reversed, and the output shaft (and, therefore, the chain) is now on the left side rather than on the right. The new engine also has a rack-and-pinion-style clutch-release mechanism that Yamaha claims makes for an easier clutch pull than with the previous YZ’s pushrod setup.

Yamaha has gone to a flat-slide Mikuni carburetor on the 125 this year, like those that Suzuki has been using since 1984. The carb feeds ports that have had their dimensions and locations juggled slightly, but the basics are the same. And the Yamaha Power Valve System (YPVS) is still used to alter the effective exhaust-port height according to engine rpm.

In the rear-suspension department, the transformation of the old-style, horizontal-shock Monocross system into a more modern, vertical-shock layout is now complete. Just about every year, the shock has been moved into a more-vertical position, and now the system is hard to distinguish from Honda’s. The only real difference is in the way the links are positioned at the base of the shock. The shock itself still features Yamaha’s Brake Actuated Suspension System (BASS), which decreases compression damping when the rear-brake lever is depressed, but the rest of the shock is new, with what Yamaha calls an “Ohlinsstyle" damper design.

So much more of the Yamaha is new that a list of all the detail changes would go on and on. There was, after all. a lot wrong with the old 125. Yamaha simply did what had to be done to get the bike back in the hunt—and then did just a little more.

SUZUKI RM125

A FEW YEARS AGO, THE 125 CLASS AT MOST LOCAL races could have been renamed the RM125 class. In recent years, however, Suzuki's 125 motocrosser has been merely good, not ex ceptional. But for 1986, the RM 125 has a new engine, rear suspension and frame as part of Suzuki's all-out effort to get back on top of the 125 class.

Among the new features in the engine is an exhaust-control device that routes exhaust gases into a chamber located in the engine’s cylinder head at low engine revs, then bypasses the chamber as engine speed increases. The idea is to have an exhaust system tuned for both low-end and top-end power. A stronger connecting rod and a flat-top piston are aimed at increasing engine longevity. The water pump is now a direct-drive unit that Suzuki claims is better than the gear-driven unit on previous models. A new closeratio transmission and rack-and-pinion clutch-release mechanism are further refinements.

Cradling the engine is a new frame that uses ovalsection side tubes to reduce chassis width. Complementing the narrower chassis is a new exhaust tailpipe that is tucked in tightly by being routed through a circular frame member. But despite all of its new features, the RM’s chassis uses the same 29-degree steering-head angle that it has for years—geometry that makes for great straight-line stability, but comparatively slow steering.

Suzuki has joined the ranks of manufacturers switching to rear-suspension linkage located under the swingarm à la Honda Pro-Link. Suzuki’s new system contains fewer parts than the previous Full Floater setup, is lighter and helps lower the bike’s center of gravity. A low, 36.7-inch seat lets shorter riders touch the ground easily, but the seat is a little thin, especially in the rear. The new gas tank is narrow and placed lower on the chassis. The side numberplates are reshaped and, when combined with the new frame and gas tank, make for a slim mid-section.

In short, there are a lot of changes on the RM125; but only the racetrack will tell if they work.

Despite having an all-new frame and chassis, the Suzuki retains the 29-degree steering-head angle it has used for some time. This kicked-out rake makes for nice straight-line control over high-speed bumps, but it causes slow steering in the tight stuff. And, like past RMs, the front tire will skate if the rider gets sloppy and doesn’t weight the front end heavily in tight turns.

By the time we returned to DeAnza for the third day of testing, engine-performance differences were becoming stabilized in the riders’

minds. The Honda proved to have the broadest powerband, one that starts at fairly low revs, continues smoothly through the mid-range and ends fairly high. The KX has the most low-end power and good mid-range before signing off rather suddenly.

Yamaha’s YZ125 has vastly improved engine characteristics. The power starts meekly, but hits hard in the lower mid-range and continues to pull strongly all the way up to high revs. The Cagiva has almost no lowend at all, then hits violently as the mid-range is reached. Mid-range power continues over a reasonably broad range, but it falls off abruptly. When kept in the powerband, however, the Cagiva is truly fast. And despite its lack of low-end urge, the engine is fairly easy to keep in the powerband if the rider is quick with his clutch hand.

Suzuki’s latest 125 engine is disap-

pointing, with feeble low-end power that makes a smooth but slow transition into the less-than-exciting midrange before tapering off quickly. But the KTM’s powerbandds by far the shortest of the bunch. There’s no low-end power (it’s almost impossible to keep the engine in its powerband at times), followed by a sudden surge into the mid-range; but partway through the mid-range the engine falls off the pipe. If you wait too long to shift, the bike acts like you hit the brakes. Acceleration is strong within the limited powerband but it simply doesn’t last long enough.

Shifting precision and smoothness is extremely important on a 125 MX bike, and the Honda, Cagiva and Suzuki are the best shifters. The Kawasaki can be a little notchy at times, and the Yamaha shifts a bit hard. The KTM has a short shift lever and shifts poorly, resulting in occasional missed >

shifts. The Cagiva’s clutch has the most progressive engagement, while the KTM, CR, RM and KX clutches engage more suddenly but still controllably. The YZ’s clutch was rough and sudden from the outset, and it got worse as the days wore on. By the third day, the YZ clutch was erratic and quite noisy, although it never slipped.

There’s not so much dissimilarity in the behavior of the brakes on these

six 125s. They all offer good, secure braking, each with a slightly different feel. All have hydraulic front discs, but the CR’s requires the least amount of lever effort, with the KX and YZ a close second. The RM’s front brake has a mushy feel that bothered most of our riders. The Cagiva front brake requires more pull than the Japanese brakes do, but it is an improvement over the ’85 model. The KTM brake requires the most oomph by the rider and also has a mushy feel, but it, too, is better than last year’s brake.

A disc rear brake is standard on the KTM and the KX, but our test riders preferred the drum rear brakes on the other bikes. The KX’s brake is overly sensitive, offers little feedback and binds the rear suspension if applied too hard. A KX125 owner would probably adapt to the brake fairly quickly and then have no problem,

CAGIVA WMX125

WITH THE 1985 WORLD 125 CHAMPIONSHIP BE-

But at the same time, the Cagiva isn’t just an Italian imitation of Japanese technology; the WMX has some special features all its own. For example, the front fork has only one spring, and its compression damping is handled mainly by the left fork leg while the bulk of the rebound damping occurs in the right leg. This year, an external adjuster knob on the lower part of the righthand slider gives the rider four different rebound-damping settings. The Cagiva is the only one of the six 125s to come with an Ohlins shock as standard equipment—as it did last year-but the shock has been revalved and given a different spring for ’86. The seat is new, as well, and is now much softer, although it still is hard by Japanese-bike standards.

Last year’s WMX 125 also was criticized for being pipey, so the ’86 version has slightly different porting and a new pipe, both aimed at giving the engine a broader powerband. And the Cagiva’s power-valve system—similar in principle to Yamaha’s YPVS—is claimed to work more smoothly than last year’s.

Overall, the level of craftsmanship of the WMX is outstanding; the bike seems solid and beautifully finished. which helps it exude a high level of quality. The WMX even comes with a spares package that includes a top-end rebuild kit, a selection of carburetor jets, two chain rollers and two rear sprockets. And a plastic fork-leg/disc cover is standard eguipment.

Details like that are unheard of in this business, no matter if the bike comes from Japan or Europe. It’s clear that Cagiva is imitating no one. But others soon might be imitating Cagiva—if they’re smart.

but we found it a bother when changing bikes as often as was necessary during this comparison. The KTM’s disc acts just the opposite: A lot of push is required before anything starts to happen. But at least the KTM has a full-length stay arm and a floating caliper, so the rear suspension doesn’t lock up if the brake pedal is stomped too hard.

Non-performance considerations, such as how well a bike fits its rider,

are very personal and depend heavily on the rider’s size and build. The CR 125R seems to fit a variety of riders the best, with the KX, the Cagiva and the YZ also earning high marks. The KTM and the RM didn’t fare so well, though. The KTM’s tall seat and fat mid-section drew complaints from most riders. The RM seemed cramped and the seat-to-handlebar relationship wasn’t liked by most; the rider sits low on the Suzuki, and the

handlebar is high.

So when it all boils down to how well each bike meets the demands of competition—which is, after all, the main reason for buying a 125 motocross racebike—the battle in 1986 will be closer than ever. All of these 125s come equipped with good tires and the proper gearing (the Cagiva even is delivered with extra rear sprockets and a top-end rebuild kit), all have strong wheels and frames,

KTM-125MX

KTMTHRIVESON CHANGE. THAT S UNUSUAL FOR a European company, and is more like the philosophy favored by the Japanese motorcycle manufacturers.

This year’s KTM 125MX is no exception. Its tiny, liquid-cooled engine has new cylinder porting and a redesigned exhaust pipe, along with an ultralight DeirOrto V-throat carburetor that is claimed to provide superior fuel atomization at all rpm.

Another very un-European aspect of the 125MX is its weight. At 195 pounds dry, it is the second-lightest of these six 125-class motocross bikes. The chromemoly steel frame has a bolt-on rear subframe that’s easy to whip on and off, allowing unrestricted access to the White Power shock—which in itself is one of the lightest shocks in the business. Likewise, the aluminum swingarm and forged-aluminum arms on the shock linkage all are very light and are equipped with grease fittings for quick, easy maintenance.

Handling the front-suspension duties is a huge, upside-down White Power fork that offers tremendous rigidity. There are no external adjustments on the front end, so dialing-in just the right amount of damping requires disassembly of the fork—a time-consuming process. The fork’s unusual design also necessitates mounting the front brake’s hydraulic caliper to the bottom of the fork tube. There’s a disc brake in the rear, as well; but, unlike the Kawasaki’s, it is of the

full-floating variety.

As on previous KTMs, the 125’s seat is nicely shaped but too hard and too high (37 inches) off the ground. The white plastic bodywork is well-made, but the 2.6-gallon gas tank is rather big and fat for motocross; that extra fuel capacity will prove handy, though, for owners who like to trail-ride their KTMs, as will the 125MX’s bolt-on sidestand.

That tall seat is typical of the saddles on European motocross bikes. But overall, the KTM still is an Austrian motorcycle that has the distinct feel of something very Japanese.

and even the least competitive of this group could become a winner through the replacement or modification of some of its components. But we were testing stock motorcycles; and in totally stock condition, the Honda, the Kawasaki and the Yamaha are the most competitive.

When voting time came, however, the Honda won a landslide victory as five of our six test riders ranked it their favorite. And why not? The CR has the best fork, the best front-torear suspension balance, the widest powerband and the smoothest power. It steers wonderfully and fits a wide selection of riders, and buyers won’t need to modify it or replace parts to make it competitive.

Kawasaki’s KX 125, the king of the class in 1984 and ’85, comes in second this year. The new rear suspension works nicely, but the fork is marginal by comparison. The engine makes excellent power but doesn’t have the wide powerband of the Hon-

da, and the shifting could use some fine-tuning.

Yamaha’s all-new entry for 1986 is miles better than previous YZ125s, but the engine is no match for the KX or CR when it comes to low-end power. The new Monoshock system still has a few glitches, especially in the way it kicks entering a whooped turn, and the fork isn’t much better. And the clutch seems like it has serious problems.

The Cagiva offers high-grade workmanship that is pleasing to look at, but that’s quickly forgotten on the track when the suspension starts refusing to cooperate. And the engine could use more low-end power.

Perhaps most disappointing was the RM 125. It has a new rear suspension that works wonderfully, but that’s where the compliments stop. The engine never really comes to life anywhere, and a mushy front brake, slow steering and an odd seating position all helped drop the Suzuki to

fifth place.

That leaves the KTM125 in last place. It’s a bike with a lot of quality parts, but unfortunately, they don’t work in harmony with one another. And the KTM’s tall seat, fat mid-section, pipey engine and poor suspension all drew complaints.

Even so, it is entirely possible that you could buy a KTM, a Suzuki or a Cagiva and be completely satisfied with its performance. Because on the right track with the right rider aboard, any of these three can win races. All three brands are currently winning races in Southern California, although most have been modified, some of them extensively. And don’t be surprised if a local hot-shot in your area blows away the competition on a stock YZ or KX. They’re not the absolute best in the class, but they’re not all that far off the pace.

For our money, though, we'll take the easiest route to the checkered flagHonda’s CR 125R. S

CAGIVA

125

$2195

HONDA CR125R

$2098

KAWASAKI KX125

$2099

KTM 125MX

$2189

SUZUKI RM125

$2099

YAMAHA YZ125

$2049

View Full Issue

View Full Issue