BIMOTA

Designer motorcycles for the stout of wallet

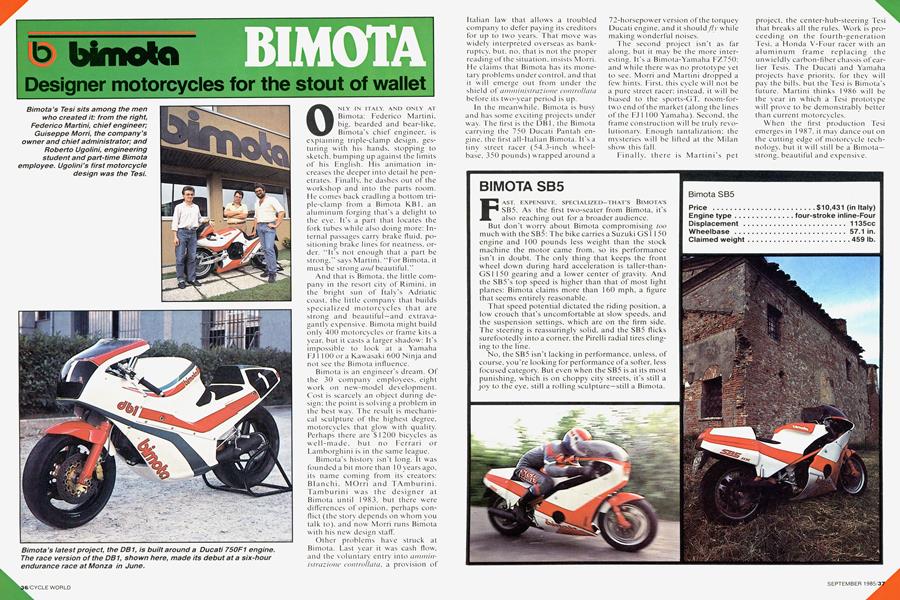

ONLY IN ITALY, AND ONLY AT Bimota: Federico Martini, big, bearded and bear-like, Bimota's chief engineer, is explaining triple-clamp design, gesturing with his hands, stopping to sketch, bumping up against the limits of his English. His animation in creases the deeper into detail he penetrates. Finally, he dashes out of the workshop and into the parts room. He comes back cradling a bottom triple-clamp from a Bimota KB1, an aluminum forging that's a delight to the eye. It's a part that locates the fork tubes while also doing more: In ternal passages carry brake fluid, po sitioning brake lines for neatness, or der. "It's not enough that a part be strong." says Martini. "For Bimota, it must be strong and beautiful."

And that is Bimota, the little company in the resort city of Rimini, in the bright sun of Italy’s Adriatic coast, the little company that builds specialized motorcycles that are strong and beautiful—and extravagantly expensive. Bimota might build only 400 motorcycles or frame kits a year, but it casts a larger shadow: It's impossible to look at a Yamaha FJ l l 00 or a Kawasaki 600 Ninja and not see the Bimota influence.

Bimota is an engineer’s dream. Of the 30 company employees, eight work on new-model development. Cost is scarcely an object during design: the point is solving a problem in the best way. The result is mechanical sculpture of the highest degree, motorcycles that glow with quality. Perhaps there are $1200 bicycles as well-made, but no Ferrari or Lamborghini is in the same league.

Bimota's history isn't long. It was founded a bit more than 10 years ago, its name coming from its creators: Blanchi, MOrri and TAmburini. Tamburini was the designer at Bimota until 1983. but there were differences of opinion, perhaps confiet (the story depends on whom you talk to), and now Morri runs Bimota with his new design staf'.

Other problems have struck at Bimota. Last year it was cash flow, and the voluntary entry into amministrazione controllata, a provision of Italian law that allows a troubled company to defer paying its creditors for up to two years. That move was widely interpreted overseas as bankruptcy. but. no. that is not the proper reading of the situation, insists Morri. He claims that Bimota has its monetary problems under control, and that it will emerge out from under the shield of anuninistrazione controllata before its two-year period is up.

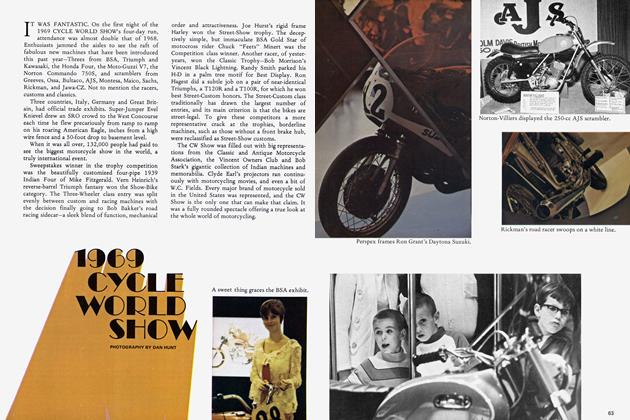

In the meanwhile. Bimota is busy and has some exciting projects under way. The first is the DB1, the Bimota carrving the 750 Ducati Pantah engine. the first all-Italian Bimota. It’s a tiny street racer (54.3-inch wheelbase. 350 pounds) wrapped around a

72-horsepower version of the torquey Ducati engine, and it should fly while making wonderful noises.

The second project isn’t as far along, but it may be the more interesting. It's a Bimota-Yamaha FZ750; and w hile there was no prototype yet to see. Morri and Martini dropped a few hints. First, this cycle w ill not be a pure street racer; instead, it will be biased to the sports-GT. room-fortwo end of the market (along the lines of the FJ 1 100 Yamaha). Second, the frame construction will be truly revolutionary. Enough tantalization; the mysteries will be lifted at the Milan show this fall.

Finally, there is Martini’s pet

project, the center-hub-steering Tesi that breaks all the rules. Work is proceeding on the fourth-generation Tesi, a Honda V-Four racer with an aluminum frame replacing the unwieldly carbon-fiber chassis of earlier Tesis. The Ducati and Yamaha projects have priority, for they will pay the bills, but the Tesi is Bimota’s future. Martini thinks 1986 will be the year in which a Tesi prototype will prove to be demonstrably better than current motorcycles.

When the first production Tesi emerges in 1 987, it may dance out on the cutting edge of motorcycle technology, but it will still be a Bimota— strong, beautiful and expensive.

BIMOTA SB5

FAST, SB5. EXPENSIVE, As the first SPECIALIZED-THAT'S two-seater from Bimota, BIMOTA’S it’s also reaching out for a broader audience.

But don’t worry about Bimota compromising too much with the SB5: The bike carries a Suzuki GS 1 1 50 engine and 100 pounds less weight than the stock machine the motor came from, so its performance isn’t in doubt. The only thing that keeps the front wheel down during hard acceleration is taller-thanGS1 150 gearing and a lower center of gravity. And the SB5’s top speed is higher than that of most light planes; Bimota claims more than 160 mph, a figure that seems entirely reasonable.

That speed potential dictated the riding position, a low crouch that’s uncomfortable at slow speeds, and the suspension settings, w'hich are on the firm side. The steering is reassuringly solid, and the SB5 flicks surefootedly into a corner, the Pirelli radial tires clinging to the line.

No, the SB5 isn’t lacking in performance, unless, of course, you're looking for performance of a softer, less focused category. But even when the SB5 is at its most punishing, which is on choppy city streets, it's still a joy to the eye, still a rolling sculpture—still a Bimota.

$10,431

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

September 1985 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

September 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupAikido: Pre-Accident Preparation

September 1985 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

September 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

September 1985 By Alan Cathcart