EDITORIAL

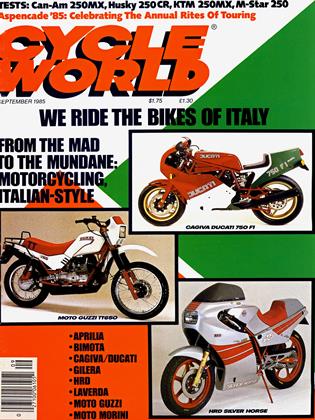

The Italians Are Coming! The Italians Are Coming!

I'LL NEVER FORGET THE SLOGAN adopted by a race-car team I once was associated with: “Your garbage is our bread and butter."

See, the team was owned by a man who held the trash-collection contract for one of Pittsburgh's more exclusive suburbs. His company had grown so profitable that the only time he ever had to get intimate with a garbage can was when his wife made him take out the trash. Instead, he concentrated on more important matters—such as spending mass quantities of money on race cars and painting slogans on them extolling the virtues of being in refuse. The point is that he earned a comfortable living through dealing in things that had been discarded by others.

In a way, the same sort of situation is taking shape in motorcycling right now. Italian bikes, as you will read elsewhere in this issue, seem to be readying for a comeback in the U.S. And most of the sales potential for these machines will be found in smaller segments of the market that the Japanese have thrown away.

Take enduro bikes, for example. Except for Kawasaki's KDX200 and Yamaha’s IT200, Japanese-built two-stroke enduros are no longer sold in the U.S. The reason? Insufficient sales volume. Fewer than 4000 Open-class Japanese two-stroke enduro machines were sold here each year during the early Eighties, and their 250cc counterparts didn't fare much better. Divide those meager numbers between three highly volume-oriented manufacturers (Honda has not sold two-stroke enduros for years), and it's easy to understand why they backed out ofthat market.

Small-displacement sportbikes have suffered a similar fate. A perfect example is Honda’s CB400F, the classy little cultbike of the mid-Seventies. Honda dropped that model in 1978 for several reasons, one of which was that only about 10,000 of them were being sold each year.

Times sure do change. In today's soft market, all of the Japanese companies, even Honda, would gladly accept all of the 10,000-unit-a-year models you could give them. But do you have any idea what the annual sale in the U.S. of 10.000 lightweight sportbikes and 8000 two-stroke enduros, or anything even close to those numbers, would mean to an Italian manufacturer? Or even to four or five Italian manufacturers if they had to divide those sales between them? It would be a windfall, a Godsend, the pot of lire at the end of the rainbow. Because these are companies that presently would regard the annual sale of just a few' hundred such machines in this country a “good year."

But that could change almost overnight. The Italians have considerable expertise in segments of the market that the Japanese have pitched into the trash; and in certain other segments that the Japanese still contest, such as the dual-purpose market, the Italians may even have more expertise than the Big Four. That added sales potential, combined with the smallish demand that already exists for larger Italian flashbikes, could give the Italian motorcycle industry the strongest foothold it has ever had in the American market.

Not only is such a thing possible, it's reasonably probable. And I, for one, am rooting for it to happen. Because motorcycling in this country could use precisely what Italian bikes can provide: a lot of romance, and a little more variety.

We don't get enough of those two ingredients in this country. The Japanese bikes, which account for over 90 percent of U.S. sales, are incredibly sophisticated and astonishingly competent but very similar in terms of personality; and for the most part, they exude all the romance and brio of a pocket calculator. German bikes are superbly designed, as well, but their overriding character is one of cold engineering logic, not of emotion. Really, of all the big-name motorcycles sold in the U.S., only Harley-Davidsons have much in the way of mystique going for them.

Italian bikes, on the other hand, are the most emotionally inspired, passionately crafted machines on two wheels. They also offer the most diverse range of personalities, with each model reflecting the temperament of the individual w ho designed it. Consequently, there is no such thing as the stereotypical “Italian" bike. An Italian designer creates only what his heart tells him to create, not what is indicated by studies.

Unquestionably, the Italians take great pride in their individuality of design. But at the same time, they also sense that Italy just may be the last outpost in the fight against total dominance of the world motorcycle market by the Japanese. That realization has encouraged the usually fragmented Italian motorcycle industry to band together for a common cause: survival. There is a movement afoot to organize a consortium of Italian manufacturers that would, among other things, help the Italians to be more competitive with the Japanese in America. One of the consortium's objectives would be to set up and maintain a network of shops that would sell several brands of Italian motorcycles at the exclusion of all other marques.

That concept is not w ithout its pitfalls, of course, but w ith a little hard work and some intelligent planning, the Italians could transform their involvement in the U.S. from one of their smallest ventures to perhaps their largest and most profitable market anywhere. Best of all. everyone involved would benefit, not just the Italians. Those passionate motorcycles of Italy would add some muchneeded effervescence to a market that has gone decidedly flat; American riders would get a more comprehensive selection of models to choose from; and the Japanese would get a healthier marketplace.

Apparently, that trashman had the right idea: Garbage cun be turned into bread and butter. —Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

September 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1985 -

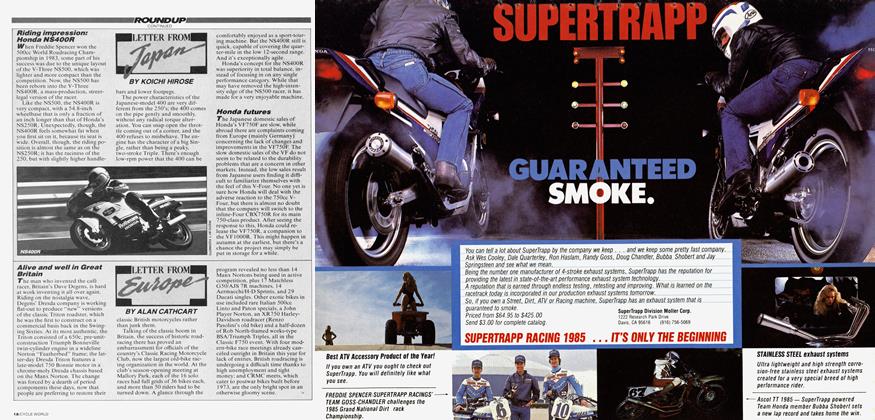

Roundup

RoundupAikido: Pre-Accident Preparation

September 1985 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

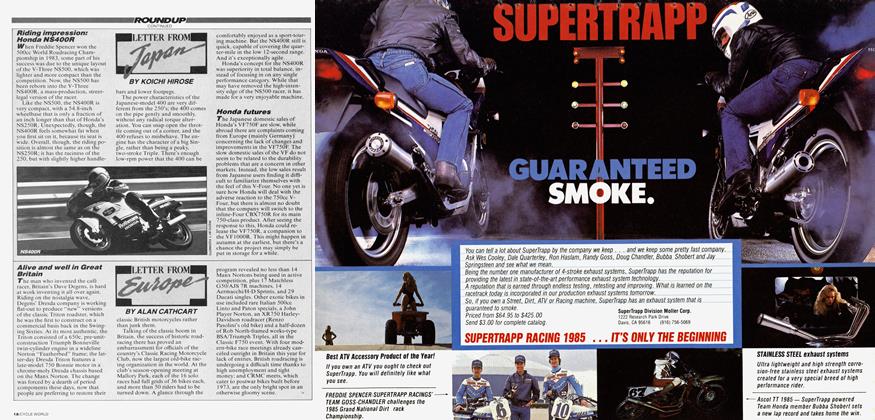

RoundupLetter From Japan

September 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

September 1985 By Alan Cathcart -

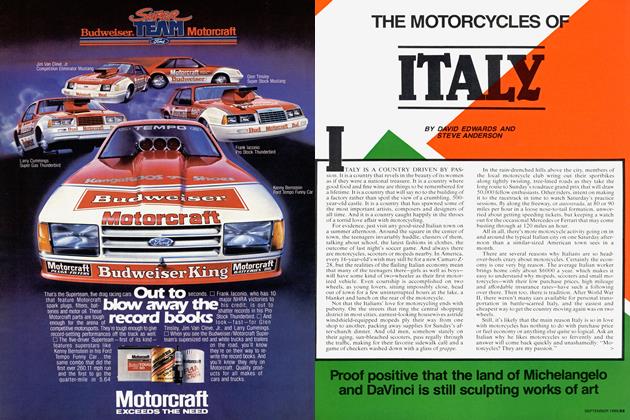

Special Feature

Special FeatureThe Motorcycles of Italy

September 1985 By David Edwards, Steve Anderson