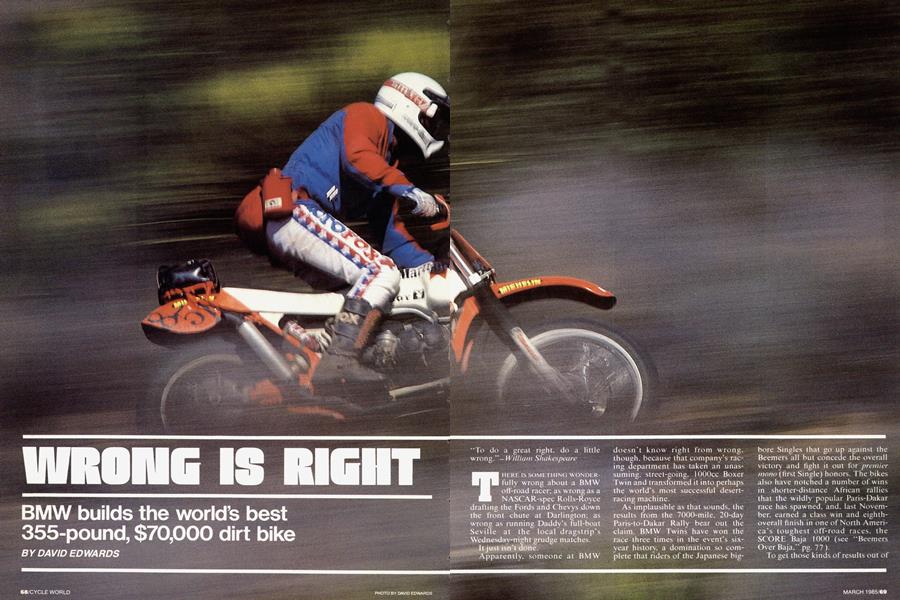

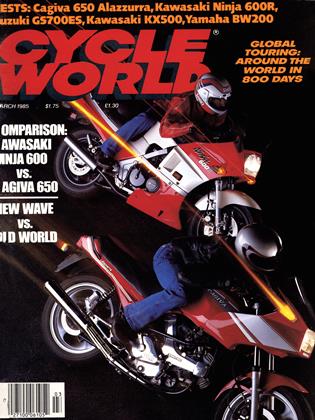

WRONG IS RIGHT

BMW builds the world's best 355-pound, $70,000 dirt bike

DAVID EDWARDS

“To do a great right, do a little wrong."— William Shakespeare

THERE IS SOMETHING WONDERfully wrong about a BMW off-road racer; as wrong as a NASCAR-spec Rolls-Royce drafting the Fords and Chevys down the front chute at Darlington; as wrong as running Daddy’s full-boat Seville at the local dragstrip's Wednesday-night grudge matches.

It just isn’t done.

Apparently, someone at BMW doesn’t know right from wrong, though, because that company’s racing department has taken an unassuming, street-going, 1000cc Boxer Twin and transformed it into perhaps the world’s most successful desertracing machine.

As implausible as that sounds, the results from the 7000-mile, 20-day Paris-to-Dakar Rally bear out the claim. BMW Twins have won the race three times in the event’s sixyear history, a domination so complete that riders of the Japanese bigbore Singles that go up against the Beemers all but concede the overall victory and fight it out for premier mono (first Single) honors. The bikes also have notched a number of wins in shorter-distance African rallies that the wildly popular Paris-Dakar race has spawned, and. last November. earned a class win and eighthoverall finish in one of North America’s toughest off-road races, the SCORE Baja 1000 (see “Beemers Over Baja." pg. 77 ).

To get those kinds of results out of such an unlikely machine, BMW has had to apply copious amounts of Right—to the tune of an estimated $70,000. And while that figure may at first seem a bit extravagant, consider just how wrong a BMW is for off-road racing. The major offender is the opposed-Twin motor, certainly a lovable enough specimen in street guise, even if it is a bit long in the tooth. But put that same engine in a racing frame and run it across unfamiliar terrain at speeds often in excess of 100 miles an hour, and suddenly those jutting cylinders become ripe targets for every rock along the trail. And don’t forget the shaft final drive, a nice feature for long-distance touring but all wrong for dirt racing, where its effects on weight transfer, suspension compliance and unsprung weight all are negative.

Still, if the Germans wanted to go racing, that’s the engine and drivetrain they were stuck with. So, with more than a little Teutonic stubborness showing, they leaned on the engine a bit, built a special frame, shored up the suspension with heavyduty components, hung a 12-gallon fuel bladder over the frame tubes, hired some talented riders, and set out to do a latter-day General Rommel number in the African desert. The end result: two wins in the last two Paris-Dakar events.

With those successes under its belt, it’s not surprising that BMW launched an assault on the Baja 1000. But Baja is not Africa, and the challenge of a one-day, 1000-mile (730-mile, actually), day-and-night team race on a tighter, rougher course is quite different from that of a threeweek, 7000-mile, daylight-only solo event on more-open terrain. Indeed, Baja and BMW seem so incompatible that last year’s eighth-overall/first-inclass finish is almost as impressive as a Paris-to-Dakar win. We at Cycle World, in fact, were so impressed that we wanted to see for ourselves just exactly what kind of Right—or magic, perhaps—had been bestowed on this unlikely behemoth to allow it to even finish a Baja race, let alone place highly in one.

When we picked up the BMW, it was in exactly the same condition as when it had finished the race, including a light splattering of Baja mud. The only exception was a new front wheel and tire, which demonstrated BMW’s faith in the big Twin’s reliability. The bike was given a quick once-over to check for loose nuts and bolts, and we then set out for the wilds of Baja and a 400-mile trek that would include parts of the Baja 1000 racecourse.

continued on page 77

A measure of BMW's seriousness about the Mexican race is that the Baja bike differs greatly from the Paris-Dakar model. Because fuel stops are closer in Baja, the monster fuel tank gave way to a beautifully crafted 4.3-gallon fiberglass unit. The frame got a reworking, too, with the wheelbase shrunk to a still-long 60 inches in hopes of making the bruiser more agile through the rocks. BMW chose to go with a lightflywheeled motor of just over lOOOcc, geared to pull 1 18 mph, although engines up to 1 lOOcc, capable of a staggering 130 mph. are in BMW’s race shop.

When it came to suspension, wheels, tires and brakes, BMW apparently felt a need to call in its neighboring European countries for help. Although the rear brake is standard BMW, the front brake is an Italian Brembo caliper with an floating aluminum disc; Italy also supplied the 12-inch-travel Marzocchi fork; 1 1.2 inches of rear-wheel travel are provided by a Dutch-built, 17-inchlong, White Power single shock; the rear wheel is a Spanish Akront; the front a Swedish Nordisk; both wheels are shod with French-made Michelin Desert tires, the back a titanic 140/ 90-17, the front foam-filled to preclude punctures.

Even before we got to ride the BMW and see for ourselves how those various components worked together, it was apparent that this bike was special, more so than just being a hand-built factory racer. Perhaps it was the incongruity of that spreadout lump of an engine stuck into a serious dirt-bike frame; perhaps it was the knowledge of all the manhours and deutschmarks that had been lavished on the bike; or perhaps it was something as simple as the ultra-white-and-fl ou resent-red paint job. This was one motorcycle that had a presence. We could feel it in the stares the bike got as it was being trucked down the highway. We could feel it in the way other dirt-bikers were drawn to the Beemer; other motorcycles, even Test Editor Ron Griewe’s tricked-to-the-gills XR500 Lite, didn't stand a chance when the BMW was around.

The XR got its revenge out on the tight, rocky trails, though, because no matter what magic had been worked on the BMW, it still is a big, 355pound motorcycle with an engine more than two feet wide; and threading anything that heavy and that wide through rough sections is tiring, imprecise work. All in all, though, the BMW handles far better than it has a right to. As raced, the suspension was set up for a full-attack charge at Baja’s killer whoops, which made it too stiff even for fast trail riding. We backed off the shock’s spring preload and bled all the air out of the fork, and the bike simply barged its way through most obstacleswithout much deflection, although the front end did bottom occasionally.

Turns were a different matter altogether. Through the various complexities of shaft-drive effect, a long wheelbase, a relatively short swingarm, a 31-degree rake and cylinder heads that insisted on occupying the space normally reserved for a steadying boot, we never really got the hang of pitching the big Beemer full-bore into a corner. We’ve seen films of the team riders doing it, so we know there’s a way to get the front end to stick and the back end to track accurately; the method was just beyond us. Later we learned it takes BMW team riders three weeks to a month to get comfortable on the bikes.

Still, it’s easy to see how the BMW does so well in races that have a goodly number of straight sections, because if its rider can keep the opposition in sight through the rough portions and tighter turns, a top-gear blast will have him in front before the next slow section. The way the bike accelerates up to, and beyond, 100 miles an hour is almost frightening. In fifth-gear roll-ons, the BMW absolutely murdered Griewe’s XR, which has an engine not unlike those in the factory Honda desert bikes.

And when it comes to reliability, the BMW certainly seems to have no problem. Even with the race miles and almost another 400 of brisk trail riding on the bike, it never missed a beat. We did lose one swingarmpivot locknut, which broke through its safety wiring. We applied more safety wire and were on our way.

If the Baja BeeEm does have an Achilles’ Heel, it’s the exhaust system, which is routed underneath the frame tubes and is devoid of any kind of skidplate. When we took delivery of the bike, the lower portions of the pipes were already crushed to half their diameter; a few bone-jarring landings by us added to the damage, pulling apart the balance-tube halves in front of the engine. Griewe cheerfully remedied the malady with a rock (aka a “Baja hammer’’) and an empty Mexican beer can.

Whether or not the BMW’s topspeed advantage and engine reliability will ever be enough to bring the BMW an overall win in the Baja peninsula depends largely on the course’s layout. Recently, the course has been a multi-loop affair with plenty of rocks and slow sections. But there has been talk of resurrecting the old point-to-point run from Ensenada to La Paz. On that course, a BMW would stand a good chance of winning outright.

If that does happen, there’ll be a lot of slack-jawed people at the finish line. But the BMW folks won’t be among them. As far as they’re concerned, this overweight, unwieldly motorcycle, powered by an out-ofplace, supposedly old-fashioned engine, can do absolutely no wrong.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

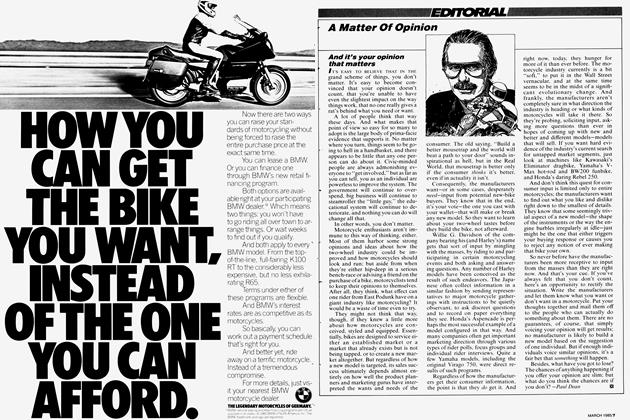

EditorialA Matter of Opinion

March 1985 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1985 -

Departments

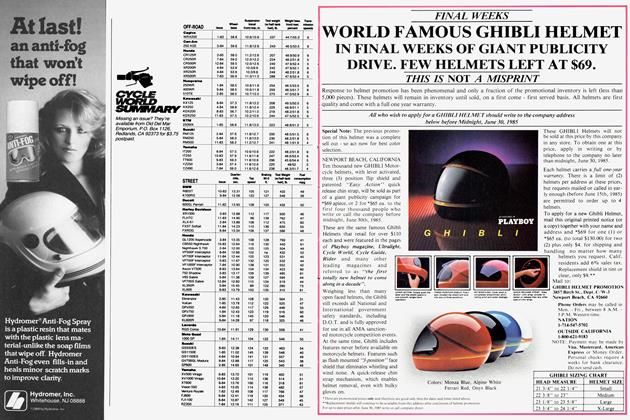

DepartmentsSummary

March 1985 -

Roundup

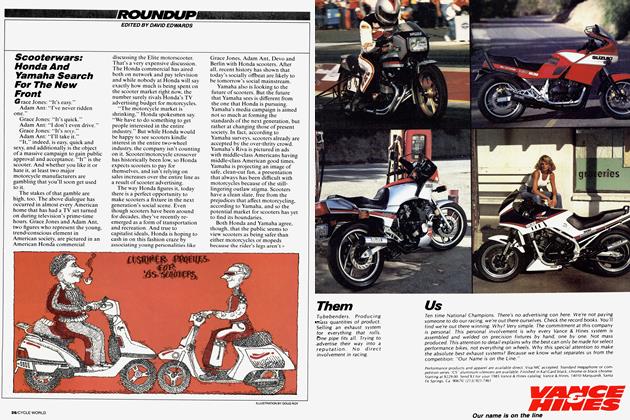

RoundupScooterwars: Honda And Yamaha Search For the New Front

March 1985 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupThe $590 Million Engine Rebuild

March 1985 -

Roundup

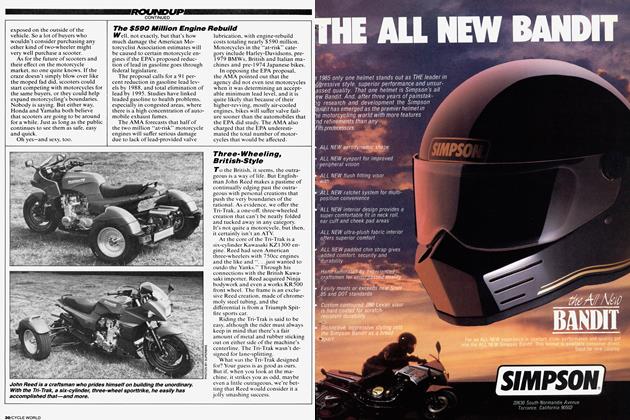

RoundupThree-Wheeling, British-Style

March 1985