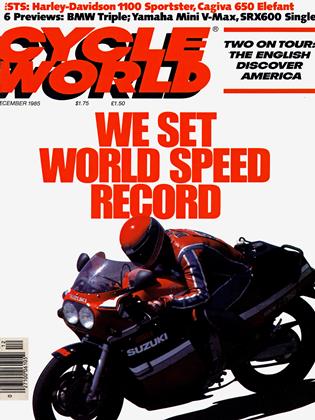

NOW I KNOW WHY THEY’RE CALLED "THE PITS”

I WAS JUST A LITTLE HURT WHEN THE RIDING TEAM FOR Cycle World's record attempt was announced and my name was not on the list. I guess Editor Dean reckoned that my rather, er, generous frontal area would be detrimental to the top speed of the GSX-Rs. But I was heartened somewhat when Dean asked if I would head up the pit operation at the Uniroyal track. Wanting to be a part of the team effort, I quickly— perhaps too quickly—agreed to give it my best. At the time, I had no idea of the 90-plus pit stops that would be involved, or about the monumental thirst and caloric requirements of 17 people operating for 24 hours in truly nasty heat.

Actually, once we got underway, the pit operations went rather well. Thanks to Associate Art Director Dean Koga, our three observers from Suzuki, Gary Gallagher the Metzeier man, the track’s sales manager, Mike Pickholz, and the riders themselves, there always were candidates for pit duty.

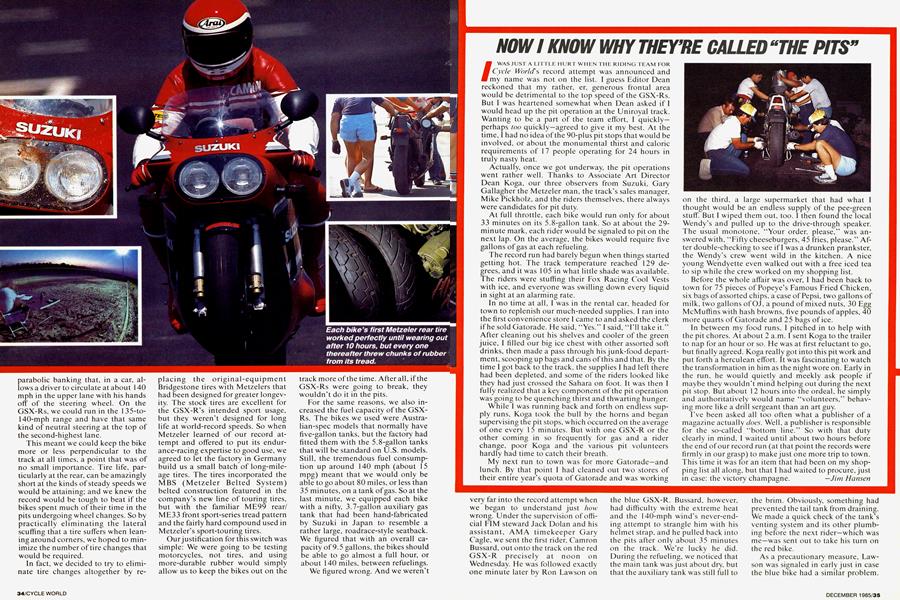

At full throttle, each bike would run only for about 33 minutes on its 5.8-gallon tank. So at about the 29minute mark, each rider would be signaled to pit on the next lap. On the average, the bikes would require five gallons of gas at each refueling.

The record run had barely begun when things started getting hot. The track temperature reached 129 degrees, and it was 105 in what little shade was available. The riders were stuffing their Fox Racing Cool Vests with ice, and everyone was swilling down every liquid in sight at an alarming rate.

In no time at all, I was in the rental car, headed for town to replenish our much-needed supplies. I ran into the first convenience store 1 came to and asked the clerk if he sold Gatorade. He said, “Yes.” I said, “I’ll take it.” After cleaning out his shelves and cooler of the green juice, I filled our big ice chest with other assorted soft drinks, then made a pass through his junk-food department, scooping up bags and cans of this and that. By the time I got back to the track, the supplies I had left there had been depleted, and some of the riders looked like they had just crossed the Sahara on foot. It was then I fully realized that a key component of the pit operation was going to be quenching thirst and thwarting hunger.

While I was running back and forth on endless supply runs, Koga took the bull by the horns and began supervising the pit stops, which occurred on the average of one every 15 minutes. But with one GSX-R or the other coming in so frequently for gas and a rider change, poor Koga and the various pit volunteers hardly had time to catch their breath.

My next run to town was for more Gatorade—and lunch. By that point I had cleaned out two stores of their entire year’s quota of Gatorade and was working on the third, a large supermarket that had what I thought would be an endless supply of the pee-green stuff. But I wiped them out, too. I then found the local Wendy’s and pulled up to the drive-through speaker. The usual monotone, “Your order, please,” was answered with, “Fifty cheeseburgers, 45 fries, please.” After double-checking to see if I was a drunken prankster, the Wendy’s crew went wild in the kitchen. A nice young Wendyette even walked out with a free iced tea to sip while the crew worked on my shopping list.

Before the whole affair was over, I had been back to town for 75 pieces of Popeye’s Famous Fried Chicken, six bags of assorted chips, a case of Pepsi, two gallons of milk, two gallons of OJ, a pound of mixed nuts, 30 Egg McMuffins with hash browns, five pounds of apples, 40 more quarts of Gatorade and 25 bags of ice.

In between my food runs, I pitched in to help with the pit chores. At about 2 a.m. I sent Koga to the trailer to nap for an hour or so. He was at first reluctant to go, but finally agreed. Koga really got into this pit work and put forth a herculean effort. It was fascinating to watch the transformation in him as the night wore on. Early in the run, he would quietly and meekly ask people if maybe they wouldn’t mind helping out during the next pit stop. But about 12 hours into the ordeal, he simply and authoritatively would name “volunteers,” behaving more like a drill sergeant than an art guy.

I’ve been asked all too often what a publisher of a magazine actually does. Well, a publisher is responsible for the so-called “bottom line.” So with that duty clearly in mind, I waited until about two hours before the end of our record run (at that point the records were firmly in our grasp) to make just one more trip to town. This time it was for an item that had been on my shopping list all along, but that I had waited to procure, just in case: the victory champagne. —Jim Hansen

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

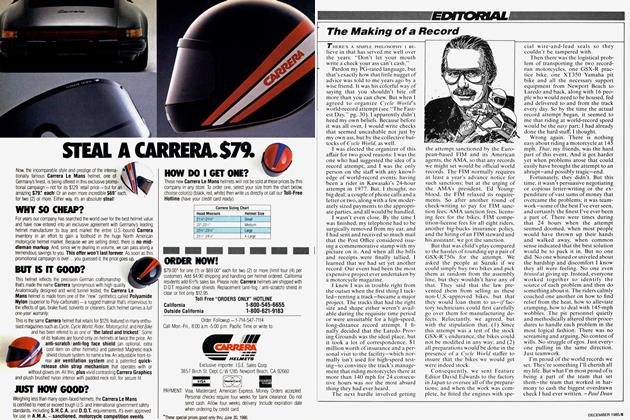

EditorialThe Making of A Record

DECEMBER 1985 By Paul Dean -

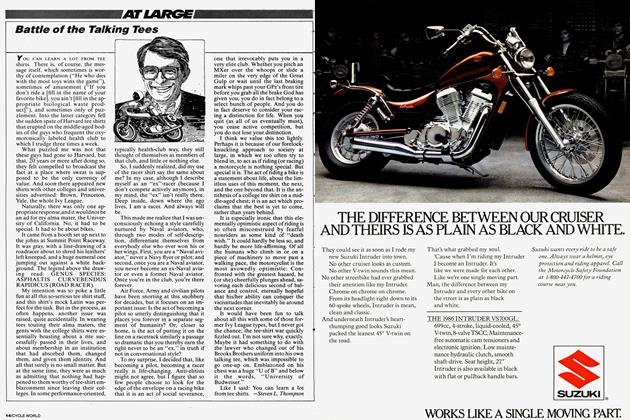

At Large

At LargeBattle of the Talking Tees

DECEMBER 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

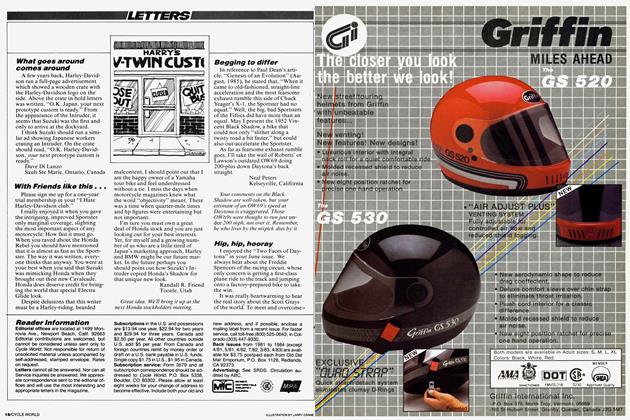

Letters

LettersLetters

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Walkman Cometh

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

DECEMBER 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

DECEMBER 1985 By Alan Cathcart