AT LARGE

Models of Respectability

THE WINTER OF 1960 WAS A PARTICUlarly tough one in England. I was living at RAF Sculthorpe in East Anglia, and as the dreary winter months dragged on, I suffered cabin fever as badly as anyone ever had. So when the Rec Officer called for a glide-off in the base gymnasium, I attacked the project with glee. The goal was to build the best hand-launched glider.

When I arrived, the gym was packed. Ed expected that other kids like me would compete. But I hadn’t expected the aircrew. Pilots, navigators, bombardiers. Scores of them. And they had scores of gliders, too. Not just little dime-store constructs, but complex, slide-ruled gems. I looked around and realized something important for the first time, something about models and men.

As a kid who built models obsessively, I figured that models were a kid’s game. That night, I learned differently. As I watched a fighter-pilot colonel intently adjust his tiny balsa creation. I understood for the first time that there was as much for adults in models as there was for kids. I

Almost a decade and a half later, I was back in England, at a base southwest of Sculthorpe. And this time, I was getting some hands-on insight into why those pilots labored so intensely on their models. Now I was an adult, roadracing every weekend, yet there was still time, somehow, for something else: time for models.

They were Tarquinio Provini’s then-new Protar Moto Modelli. 1 discovered them in a little shop in Cambridge, and without even wondering why, I entered into building them with complete abandon. Soon, my little suite in the old RAF club at Feltwell was dotted with the results: Hugh Anderson's exquisite 125 GP Suzuki, Hailwood’s 250 GP Six, the awesome Moto Guzzi V-Eight, Max Deubel’s BMW sidecar—as many as I could buy and build. My friends—pilots and racers—said nothing about it; they were building them. too. The subject of why never arose.

And then, another decade and half after that model-building spurt, the subject of why snapped into focus. The proximate cause was the reshuffling of my office furniture. After everything had been moved, there suddenly appeared a long, blank wall in my office. I stared at it for a moment, then realized that it was exactly suited to the shape of a 1969 Kawasaki A 1 R. The A 1 R was a bike I had raced when it was new, a rotaryvalved two-stroke Twin of ingenious engineering and a finish that would have been the envy of most Rolls Royce owners had they known of it. Before the Green Meanie paint job became the signature of racing Kawasakis, the company painted its racers in cream and a deep red that was somewhere between maroon and oxblood. The alloy fuel tank of the A1R was a thing of beauty in itself, and the paint must have taken some mamasan in Akashi a week to rub to pearlescent perfection.

That AIR won me a single race and precious little else, but I still have a soft spot for it. So when the wall appeared, naked and inviting, I knew the bike was perfect for it.

But I also knew that the odds against finding one in fit condition to restore were high. I had spent too much time and money restoring my old Commando Production Racer not to be wise to the boobytraps of a long-obsolete Kawasaki. Those long odds brought me back to models. Why not replace the unobtainable “real” A1 R with a model?

Surprisingly, the thought made me uneasy. Probing for the reason, I concluded that I had been long enough away from model-building to forget the truths the activity embodies. I was close to thinking of them as toys, pathetic simulacra of the “real thing.”

My friends, as usual, reeled me in. My architect friend, an ex-racer. compared the superbly detailed Tamiya GP models that decorate his office with the full-size Harris and Dresda Hondas that he built. “Technology demonstrators,” he calls the models, noting further that building them keeps him close to the current state of the GP art. The archaeology professor who crafts minutely detailed airplanes concurred, adding notes about the joys of an object that is built to instruct and then lingers to please aesthetically. The advertising executive—a current racer—reminded me of how a model captures a sense of history as no book or photo can.

The last explanation struck home hard. As he talked, I suddenly remembered how Ed felt last summer, when Ed arrived at the Moto Guzzi factory and museum in Mandello del Lario on Lake Como in Italy. The Museum is really a couple of long, narrow bays on the second floor. Our guide, a very pregnant, very nice lady, naturally wanted to begin us at the beginning, but I strained to see the fairing of the only bike I really cared about. When I spotted it, I felt a weird sense of déjà vu. I walked slowly toward the 1956 500cc VEight and simply stared at it. Thirteen years before, I had labored through an English winter to get all those fantastically detailed plastic bits just right, marvelling at the brilliance of the engineers who could make such a contraption work. And now, the Real Thing squatted on deflating tires in front of me.

“Em sorry,” our guide said, “but the engine we usually have on display is away at the moment.” And indeed, the bike wore its all-enveloping dustbin fairing, effectively hiding the heart of the beast. She obviously felt keenly embarrassed that their star exhibit was gone. It was as if a da Vinci admirer had made a pilgrimage to see the Mona Lisa and found only an empty frame.

But the Guzzi V-Eight wasn’t the Mona Lisa and I had one up on any art freak. I smiled at her and shook my head. “It’s okay,” I said, “Eve built Signor Provini’s model.”

She smiled back, and I think she understood immediately. It’s taken me a little longer.

—Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

August 1985 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1985 -

Roundup

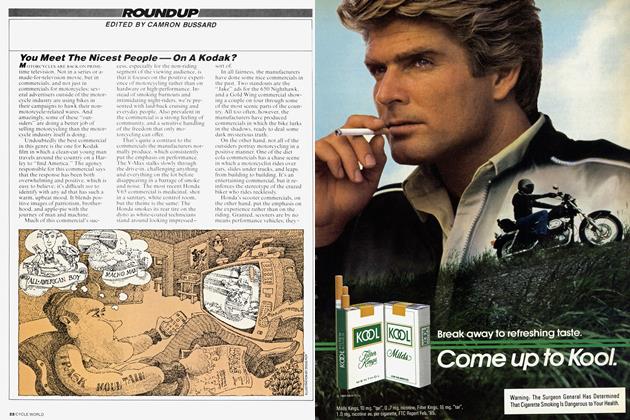

RoundupYou Meet the Nicest People—On A Kodak?

August 1985 By Camron Bussard -

Roundup

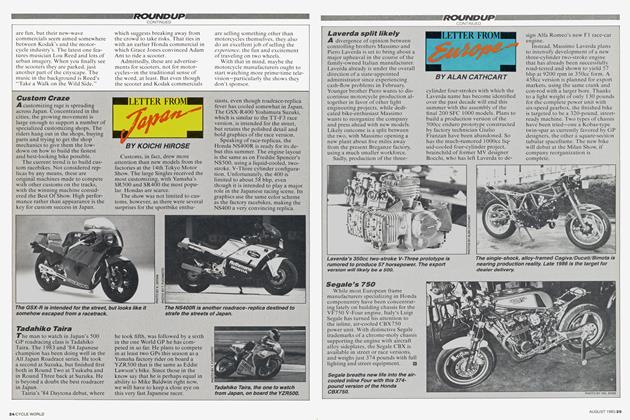

RoundupLetter From Japan

August 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

August 1985 By Alan Cathcart -

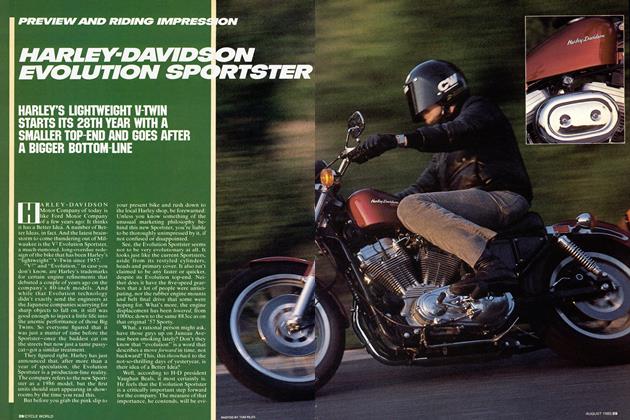

Preview And Riding Impression

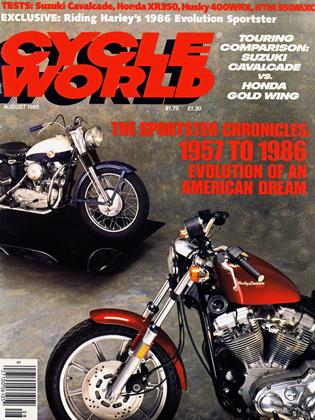

Preview And Riding ImpressionHarley-Davidson Evolution Sportster

August 1985