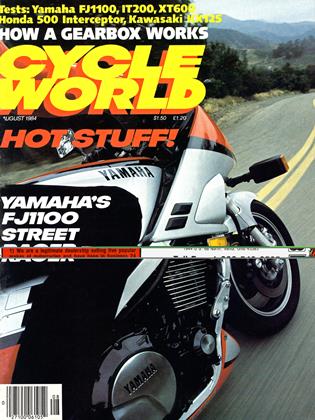

FJ1100 EVOLUTION: CONSERVATIVE BY DESIGN

It would be easy to think of the FJ1100 merely as Yamaha’s quick-and-dirty attempt to catch up with the competition in the literbike sport class. After all, its engine is “only” an air-cooled inline Four, a type considered passé by many riders in these times of liquid cooling and V-motors. And other aspects of the FJ, specifically its included valve angle (quite wide by current standards) and shortage of high-tech features, suggest that perhaps Yamaha isn’t capable of playing high-performance hardball in the liter-class league.

If you came to such a conclusion, you’d be wrong. As wrong as knobbies on a dragbike.

Truth is, the FJ 1100’s development has not been a quick process at all. The concept first saw the light of day on a drawing board way back in 1980, and it has undergone countless revisions, refinements and restylings between those original sketches and what you can buy today.

Neither was the FJ1 l’s engine configuration chosen because it would be economical to manufacture, expeditious to get into production or because Yamaha lacked the technological prowess to build anything more innovative. Yamaha in fact seriously considered a wide variety of engines having from two to six cylinders, some with liquid cooling, some with V-type cylinder layouts. But before committing to any configuration, Yamaha first conducted rider surveys in major, motorcycle markets all around the world. And only after all that data was compiled and closely scrutinized did Yamaha’s designers decide on an air-cooled inline-Four—the type of engine that most of those riders told them they preferred.

Moreover, those same riders indicated that they wanted a simple inline Four, one that incorporated a minimum of high-tech gadgets and sales gimmicks. They asked for an extraordinarily fast bike, of course, that would offer superb sport-type handling and exceptional reliability; but they still wanted all of that in a straightforward package.

It’s no wonder, then, that beneath its roadracer-replica bodywork, the FJllOO is so conservative, so traditional, so ... so usual. But despite the company’s self-imposed mandate to build a mechanically unremarkable performance bike, there was never any consideration given to the idea of simply rehashing the XS1100, Yamaha’s shaft-driven literbike of the late Seventies. The marketing people felt that the time had come and gone for those kinds of do-everything, all-things-for-all-riders models, and that the need for the Eighties was for a specialized performance bike.

Yamaha also wanted its new model to be a “world” bike, one that would fill specific needs in all major markets, not just in the U.S. But because the world epicenter of sportbiking enthusiasm seems to be in Europe, Yamaha relied on information it had gathered from riders Over There more than from those on this side of the Atlantic, where custom-styled models proliferate.

Conversely, the engineers didn’t want to try to build a superior streetbike from something that had started life as a racer, which is the method that many European riders had suggested. Instead, Yamaha’s goal was to start from scratch and build a literbike of unsurpassed goodness, one that would offer the performance and the image of a thoroughbred racer but would also be competent for long-distance and general-purpose riding; a motorcycle that would have unparalleled big-bike power and performance yet wouldn’t feel big; a bike that would have racy, modern but, above all, functional styling. In short, Yamaha wanted to build the best all-around performer in the class, even if the finished product might not be able to flash the most impressive technical credentials.

If you believe that Yamaha somehow failed to make good on that promise, if you still think that the FJllOO is a low-buck post-entry rather than a legitimate contender in the literbike race, there’s only one thing left to do: Ride the bike. You’ll remain a doubter no more. EE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Editorial

August 1984 By Paul Dean -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

August 1984 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Round Up

August 1984 -

Special Features

Special FeaturesHow Motorcycles W·o·r·k 4

August 1984 By Steve Anderson -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Race Watch

August 1984 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Service

August 1984