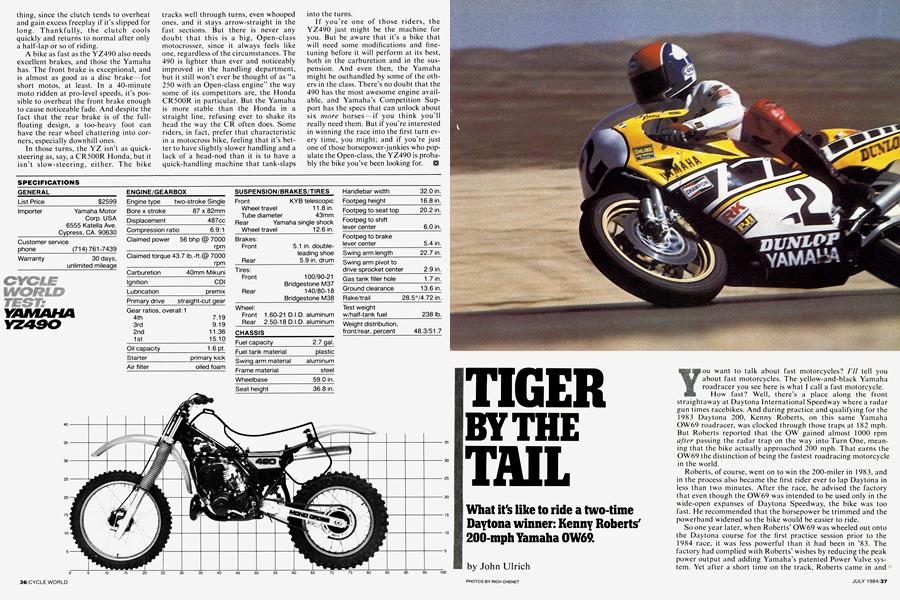

TIGER BY THE TAIL

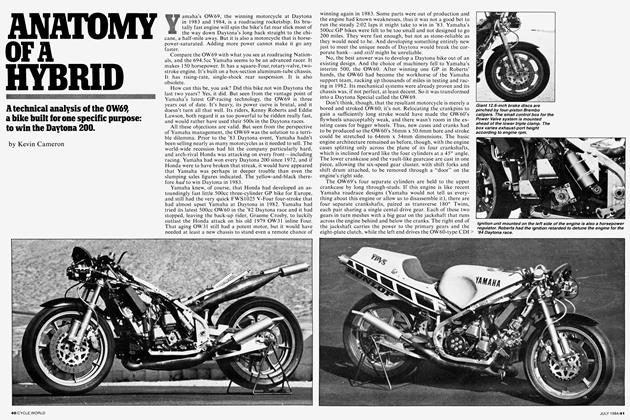

What it's like to ride a two-time Daytona winner: Kenny Roberts' 200-mph Yamaha OW69.

John Ulrich

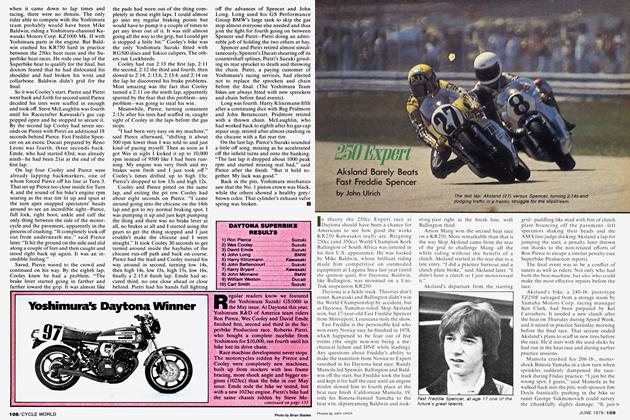

You want to talk about fast motorcycles? I’ll tell you about fast motorcycles. The yellow-and-black Yamaha roadracer you see here is what I call a fast motorcycle. How fast? Well, there’s a place along the front straightaway at Daytona International Speedway where a radar gun times racebikes. And during practice and qualifying for the 1983 Daytona 200, Kenny Roberts, on this same Yamaha OW69 roadracer, was clocked through those traps at 182 mph. But Roberts reported that the OW gained almost 1000 rpm after passing the radar trap on the way into Turn One, meaning that the bike actually approached 200 mph. That earns the OW69 the distinction of being the fastest roadracing motorcycle in the world.

Roberts, of course, went on to win the 200-miler in 1983, and in the process also became the first rider ever to lap Daytona in less than two minutes. After the race, he advised the factory that even though the OW69 was intended to be used only in the wide-open expanses of Daytona Speedway, the bike was too fast. He recommended that the horsepower be trimmed and the powerband widened so the bike would be easier to ride.

So one year later, when Roberts’ OW69 was wheeled out onto the Daytona course for the first practice session prior to the 1984 race, it was less powerful than it had been in ’83. The factory had complied with Roberts’ wishes by reducing the peak power output and adding Yamaha’s patented Power Valve system. Yet after a short time on the track, Roberts came in andtold the mechanics to back-off on the timing and make the jetting richer, both of which would reduce power even further but would also cut down on the bike's tendency to spin its rear wheel wildly coming out of the corners.

The mechanics made the prescribed changes, and the rest is history. Roberts won the race again, said he'd never ride at Daytona again, and the OW69 was retired, put on display as a 200-mph trophy in the lobby of Yamaha’s headquarters in Cypress, California.

A few months later, however, the OW69 was rolled out of the lobby and prepped for the track once again. But not for Roberts to ride. For me to ride. Me. On the world's fastest roadrace bike.

Gulp!

What I wanted at that point was help. Some advice from Kenny Roberts himself would have been ideal, but he was in Italy for the Imola 200. So I enlisted the aid of Eddie Lawson, who happened to be at home between Grands Prix instead of competing at Imola, since that race isn’t part of the 500cc World Championship series. Lawson had been Roberts’ teammate at Daytona on a virtually identical bike, making him the world’s second-best authority on riding an OW69.

By the time Lawson finished telling me everything he thought I needed to know about the bike, I almost wished I hadn't asked. “It’s fast," he said as the two of us blasted down a deserted twolane road in his Turbo Porsche at around 1 20 mph. We were on our way to Willow Springs Raceway, a 100-mile trip that would take us just 65 minutes, including a stop for gas. Waiting at the track would be a crew from Yamaha—and the OW69. “There's no way to explain to most people just how fast it really is because they don’t have any frame of reference,” he tells me. “They just have no idea.

“Anybody can ride a four-stroke,” Lawson continues as he weaves around a cement truck and back into our lane before oncoming traffic reaches us. “On a four-stroke you can just get on the gas and slide out of the corners. But a big two-stroke’s power is so abrupt you have to discipline yourself; throttle control is critical. These things don’t like to slide, they want to highside. They’re difficult to ride in that sense. The slightest movement of the throttle makes a big difference.”

It is a warning of sorts, and it makes me nervous. For good reason. Most of my roadracing experience is on four-strokes, Formula One and endurance bikes with 998cc and 1136cc engines and broad powerbands.

“The hardest part is getting the braking right,” Lawson goes on. “Most of the time you go in either too fast or not fast enough. I think a lot of guys who ride four-strokes rely on compression to slow down. On a four-stroke it’s easier to know where your limit is. But on a two-stroke you tend to brake too early, so you keep going in a little deeper and a little deeper until finally you get in too hot.

“Accelerating is hard, too, because the power is so abrupt. These bikes were built just for Daytona, and are completely different from the 500 I normally ride. The 500 is lighter, smaller, easier to ride, has better power. When I get on one of these after riding the 500, I can't relate to it at all. The rear tire smokes coming off the corners, and at Daytona it would spin from Turn Five, where you get on the banking, until I was straight-up on the top lane. I'd just dirt-track it all the way.”

Wonderful, I thought. What have I talked myself into here?

About an hour later, in Willow Springs' fast Turn One, I got my first clue. I had practically coasted into that turn after having gotten on and off the brakes quite early. The wish not to crash this famous and valuable racebike was bearing down on me heavily during these first few tours of the circuit, causing me to be extremely careful. Then it happened. I was just past the apex and still leaned over as I started rolling on the throttle ever so gingerly, when WHAM!—the bike literally exploded forward and the front wheel shot skyward, cocked sideways like a motocrosser in full crossup. Before I could comprehend what had happened, the power peaked, the front wheel returned to earth, still cocked sideways, and the handlebars started clicking lock-to-lock. Somehow, the Yamaha straightened out and continued its rampage down the straight section of track ahead of me. Instinctively more than deliberately, I upshifted and ran the OW up to about 9000 rpm before grabbing the brakes for Turn Two. I was halfway around that long sweeper before I realized that I had been holding my breath ever since that exit from Turn One. And I was utterly amazed that I was still upright and moving, that nothing terminal had happened as the result of my introduction to the OW69’s vicious power delivery.

It had been just a few laps into my first session on the Yamaha. The tires were new Dunlops, the engine freshly rebuilt after Daytona. Take it easy, they told me. Make sure the brakes work, scuff in the tires. Redline is 1 1,000 rpm. We won’t think poorly of you if you don’t set a lap record. Trying to ride one of these machines anywhere close to its limits— trying even to approach its limits—would be crazy, they said.

As a further precaution, the mechanics had jetted the engine rich, so rich that the power comes on at 8500 rpm, not 7500 rpm; so rich that the pipes will be soot-black when I come in; so rich that there’s no way the motor will seize, even if I do something with the throttle that I’m not supposed to do.

Still, the engine does run below the powerband, pretty strongly, in fact. But I’m trying to be conservative, to coast through the corners and not turn on the gas until I’m on the straights. The bike is so small and light—the wheelbase is 53.5 inches, the weight 305 pounds with gas—that it’s distracting. Impulse says Go Fast, conscious thought demands a cautious pace. Instinct says I’ll look bad if I don’t gas it up, reason says I’ll look worse if something goes wrong.

Looming over it all is my awareness that I’m riding Kenny Roberts’ bike. That’s an awesome weight on my shoulders, both exhilarating and horrifying, so I pull into the pits.

At least no one laughs when I come in. No one even jokes about the amount of time I spent riding below the bike’s powerband. I again talk with Lawson to get more advice on how to ride this beast. He does a good job, because by the time I’m ready to be pushed out onto the track for another session, I feel relaxed, almost eager.

I let out the clutch and snap it back in, rolling on the throttle as Bud Aksland and Keith McCarty push me away. The bike comes to life, but if I don’t work the throttle just right, the engine will die, since it seems to have almost no flywheel effect at all. So I have to slip the clutch and keep the engine above 7000 rpm to start off.

After two laps to warm up the engine and tires, I’m shifting at 10,000 rpm. The Yamaha changes gears almost imperceptibly; there’s no feeling of gears sliding and moving, no clunks. But the lack of flywheel, along with the light clutch-pull and sensitive throttle, means I’ve got to work at matching engine speed to the transmission ratios on downshifts. I never do get it quite right, but my upshifts are smooth and quick. The higher the bike revs, the easier it shifts.

Lawson was right about throttle control. I make a conscious effort to keep my hand steady on the twistgrip because the smallest movement makes the bike speed up or slow down; if you’re near 8500 rpm when that happens, it can make the difference between rolling around a corner under control and fighting for your life.

This bike may be a tank compared with Lawson’s 500, but it’s three times better than my endurance bike, a works Suzuki chassis fitted with an 1136cc GS1100 engine. It’s 100 pounds lighter, four inches shorter; its weight is carried lower and doesn’t have to be fought in a turn or though a series of esses.

The OW69 also accelerates harder than my endurance racer, harder than anything I’ve ridden other than a drag bike. The OW shoots off of the corners, hooking up and lunging forward as the front wheel lifts. It wheelies out of Willow’s Turn Two, it wheelies up the hill from Turn Three, it wheelies down the hill from Turn Four, it leaps off the crest of Turn Six, and it makes the straight leading to turns Seven and Eight seem less than half its actual length. In terms of the time perceived to cut a full lap, the OW69 makes Willow’s 2.5-mile course seem barely longer than a backyard go-kart track.

Turn open the throttle on this motorcycle and it doesn’t want to stay leaned over; it picks up speed so quickly that no leanangle is correct for more than a split-second. Which means that if a rider like me gets on the powerband while he’s still in a turn, he’ll probably wish he hadn’t. Changing direction with the gas on is a job for Kenny Roberts or Eddie Lawson; for me, the idea of dodging through traffic while accelerating on this bike is beyond comprehension.

But when I do change direction, the OW69 is stable and steady. Racetrack bumps that make any street bike work hard just don’t seem to exist when you’re on this Yamaha. And the bike is unusually low. That, and the fact that it sticks to the track like glue, allows me to easily drag my knee in Turn Eight, a fast, fast righthand sweeper. My knee also slams into the pavement in Turn Nine, skims in Turn One, plows through Turn Two, and hits regularly in Three and Four.

It’s only when I pull off the track for the final time and coast into the pits that I realize how hard I’ve been working. My forearms are pumped, my wrists are tired and I’m drenched with sweat. I’ve only been nicking into the OW’s powerband, but for me, even that has been unbelievably demanding.

Still, there’s no doubt in my mind that the OW69 is, by far, the finest piece of roadracing equipment I’ve ever ridden. Lawson's assertion that the latest 500cc works GP racers are worlds better just boggles my imagination. Given time to practice on the OW69 so I could learn how to ride it half-decently, I could race it and do well. But if I rolled it onto any starting grid tomorrow, I’d be in way over my head.

That’s what is so impressive about riders like Roberts and Lawson and Freddie Spencer and Mike Baldwin. People usually think these superstars win races and always run up front because they have the best equipment—which, to a large extent, is true. And although the OW69 certainly is what you would call a good roadrace bike, it’s not what any of those riders would call “the best equipment.” And the magic of a Roberts or a Lawson is that they can jump on a monster like an OW69 and not only race it, but also—in the case of Roberts, at least—win on it.

So while I came away from my ride both amazed and impressed, the most amazing and impressive lesson I learned was not about the OW69 but about the two men who have ridden it. And the one who has won on it. Twice. El