CYCLE WORLD PROFILE

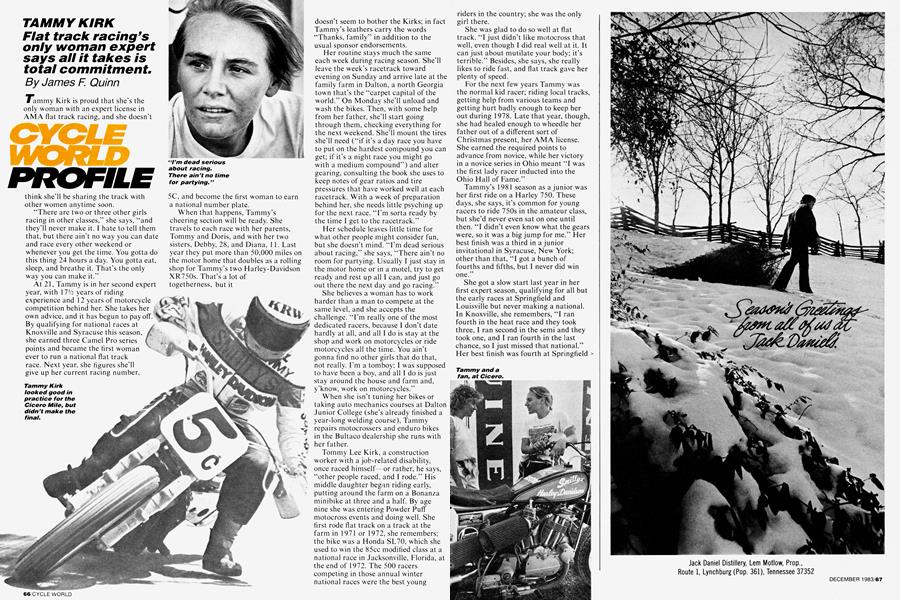

TAMMY KIRK Flat track racing's only woman expert says all it takes is total commitment.

James F. Quinn

Tammy Kirk is proud that she's the only woman with an expert license in AMA flat track racing, and she doesn’t

think she’ll be sharing the track with other women anytime soon.

“There are two or three other girls racing in other classes,” she says, “and they’ll never make it. I hate to tell them that, but there ain’t no way you can date and race every other weekend or whenever you get the time. You gotta do this thing 24 hours a day. You gotta eat, sleep, and breathe it. That’s the only way you can make it.”

At 21, Tammy is in her second expert year, with 1 7Vi years of riding experience and 1 2 years of motorcycle competition behind her. She takes her own advice, and it has begun to payoff. By qualifying for national races at Knoxville and Syracuse this season, she earned three Camel Pro series points and became the first woman ever to run a national flat track race. Next year, she figures she’ll give up her current racing number,

5C, and become the first woman to earn a national number plate.

When that happens, Tammy’s cheering section will be ready. She travels to each race with her parents, Tommy and Doris, and with her two sisters, Debby, 28, and Diana, 11. Last year they put more than 50,000 miles on the motor home that doubles as a rolling shop for Tammy’s two Harley-Davidson XR750s. That’s a lot of togetherness, but it

doesn’t seem to bother the Kirks; in fact Tammy’s leathers carry the words “Thanks, family” in addition to the usual sponsor endorsements.

Her routine stays much the same each week during racing season. She’ll leave the week’s racetrack toward evening on Sunday and arrive late at the family farm in Dalton, a north Georgia town that’s the “carpet capital of the world.” On Monday she’ll unload and wash the bikes. Then, with some help from her father, she’ll start going through them, checking everything for the next weekend. She’ll mount the tires she’ll need (“if it’s a day race you have to put on the hardest compound you can get; if it’s a night race you might go with a medium compound”) and alter gearing, consulting the book she uses to keep notes of gear ratios and tire pressures that have worked well at each racetrack. With a week of preparation behind her, she needs little psyching up for the next race. “I’m sorta ready by the time I get to the racetrack.”

Her schedule leaves little time for what other people might consider fun, but she doesn’t mind. “I’m dead serious about racing,” she says, “There ain’t no room for partying. Usually I just stay in the motor home or in a motel, try to get ready and rest up all I can, and just go out there the next day and go racing.”

She believes a woman has to work harder than a man to compete at the same level, and she accepts the challenge. “I’m really one of the most dedicated racers, because I don’t date hardly at all, and all I do is stay at the shop and work on motorcycles or ride motorcycles all the time. You ain’t gonna find no other girls that do that, not really. I’m a tomboy; I was supposed to have been a boy, and all I do is just stay around the house and farm and, y’know, work on motorcycles.”

When she isn’t tuning her bikes or taking auto mechanics courses at Dalton Junior College (she’s already finished a year-long welding course), Tammy repairs motocrossers and enduro bikes in the Bultaco dealership she runs with her father.

Tommy Lee Kirk, a construction worker with a job-related disability, once raced himself -or rather, he says, “other people raced, and I rode.” His middle daughter began riding early, putting around the farm on a Bonanza minibike at three and a half. By age nine she was entering Powder Puff motocross events and doing well. She first rode flat track on a track at the farm in 1971 or 1972, she remembers; the bike was a Honda SL70, which she used to win the 85cc modified class at a national race in Jacksonville, Florida, at the end of 1972. The 500 racers competing in those annual winter national races were the best young riders in the country; she was the only girl there.

She was glad to do so well at flat track. “I just didn’t like motocross that well, even though I did real well at it. It can just about mutilate your body; it’s terrible.” Besides, she says, she really likes to ride fast, and flat track gave her plenty of speed.

For the next few years Tammy was the normal kid racer; riding local tracks, getting help from various teams and getting hurt badly enough to keep her out during 1978. Late that year, though, she had healed enough to wheedle her father out of a different sort of Christmas present, her AMA license.

She earned the required points to advance from novice, while her victory in a novice series in Ohio meant “I was the first lady racer inducted into the Ohio Hall of Fame.”

Tammy’s 1981 season as a junior was her first ride on a Harley 750. These days, she says, it’s common for young racers to ride 750s in the amateur class, but she’d never even sat on one until then. “I didn’t even know what the gears were, so it was a big jump for me.” Her best finish was a third in a junior invitational in Syracuse, New York; other than that, “I got a bunch of fourths and fifths, but I never did win one.”

She got a slow start last year in her first expert season, qualifying for all but the early races at Springfield and Louisville but never making a national.

In Knoxville, she remembers, “I ran fourth in the heat race and they took three, I ran second in the semi and they took one, and I ran fourth in the last chance, so I just missed that national.” Her best finish was fourth at Springfield > in an eastern regional race.

In her second expert year, Tammy has finished 14th in the mile at Knoxville (“I was running 10th, I believe, and the motorcycle tore up, so I ended up 14th”) and 13th at Syracuse. She fell without injury at the DuQuoin mile (Doris Kirk says that if Tammy falls, “for the next three or four races I don’t want to watch much”), and came in sixth in the last chance race at Hawthorne racetrack near Chicago, a course she found so dusty “you sort of had to feel your way around the corner.”

She’s doing better this year than she’d hoped; she believes it takes at least two years to learn how to tune and ride the 750s well. “All these rookies get so disappointed. I say, ‘Hey, if you make just one national the first year that’s excellent. You ain’t gonna go out and just win unless you got a factory behind you or the best motorcycles I’ve seen.

It’s hard.' The first two years you get the equipment sorted out, get a fast bike and learn how to ride a racetrack. And the third year, go out and win.”

Tammy has found a lot of help at the racetrack. Team Honda’s Terry Poovey has given her plenty of advice on gear ratios and other technical matters, and Tex Peel, Ricky Graham’s tuner, has also been helpful; in addition to advice on bike preparation, he did the head and cylinder work for her bikes this season. She’s begun picking up sponsors, too, and currently receives parts and equipment from Harley-Davidson, Carlisle tires, KRW helmets, Wiseco pistons, and a list of other suppliers that includes Bubba Shobert’s sponsor, Ken Parker of Esquire motor homes, who gave the Kirks an excellent deal on their rig.

Tammy doesn’t get too much pressure from friends and neighbors to fit some preconceived lifestyle; in fact, she says, quite a few neighbors in Dalton don’t even know she races. Her doctor often asks when she’ll quit racing and find a job. “I tell her that if I do real good in racing, more than likely I’ll end up with one of the big factories or doing something dealing with motorcycles, because I love motorcycles, I love racing, and I’m gonna try and stay in the business.”

At 21, Tammy figures she has at least five more years as a racer, and that means five more seasons of long mileage and late nights in the shop, five more winters spent pounding around the trails of the family farm on “the heaviest motocrosser I can find” to stay in shape. “I’m gonna stay in there as long as I can stay competitive,” she says, “If I start seeing myself running slow and I can’t stay up with the crowd, I’ll quit. I can’t stand to do real terrible, because I love to win.” 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

December 1983 By Allan Girdler -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

December 1983 -

Departments

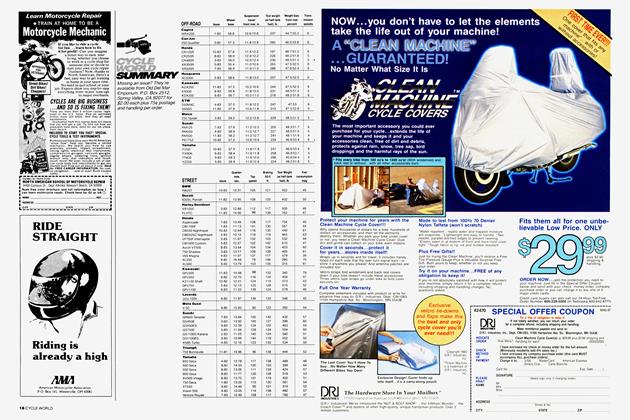

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

December 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

December 1983 -

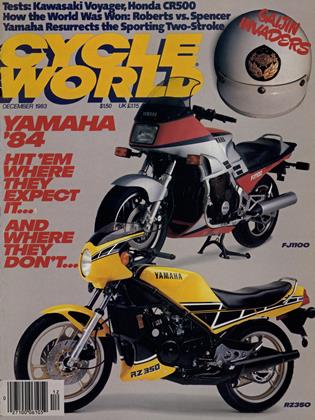

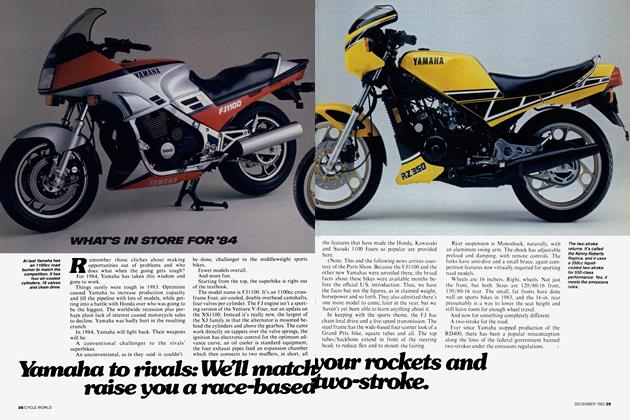

What's In Store For '84

What's In Store For '84Yamaha To Rivals: We'll Match Your Rockets And Raise You A Race-Based Two-Stroke.

December 1983 -

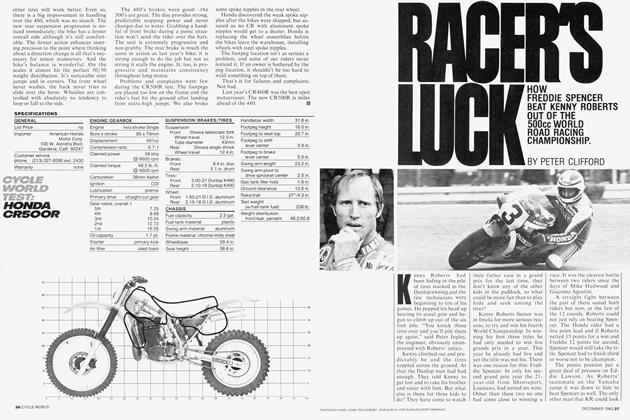

Competition

CompetitionRacer's Luck

December 1983 By Peter Clifford