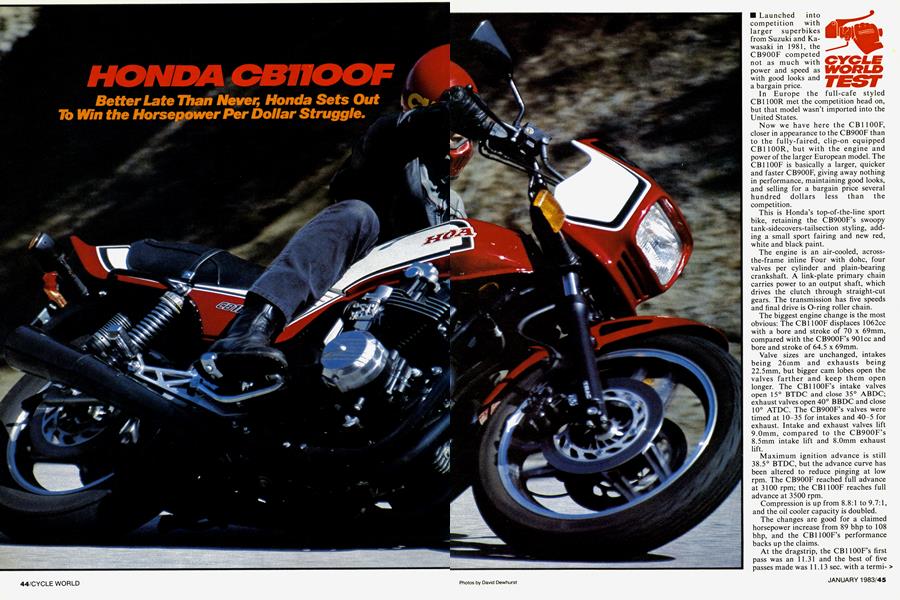

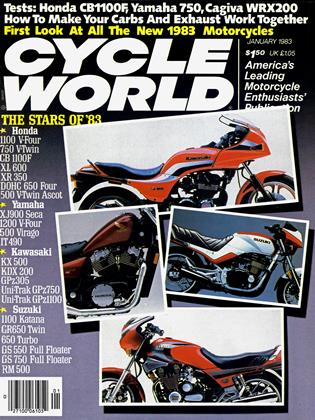

HONDA CB1100F

Better Late Than Never; Honda Sets Out To Win the Horsepower Per Dollar Struggle.

CYCLE WORLD TEST

▪ Launched into competition with larger superbikes from Suzuki and Kawasaki in 1981, the CB900F competed not as much with power and speed as with good looks and a bargain price.

In Europe the full-cafe styled CB1100R met the competition head on, but that model wasn't imported into the United States.

Now we have here the CB1100F, closer in appearance to the CB900F than to the fully-faired, clip-on equipped CB1100R, but with the engine and power of the larger European model. The CB1 100F is basically a larger, quicker and faster CB900F, giving away nothing in performance, maintaining good looks, and selling for a bargain price several hundred dollars less than the competition.

This is Honda's top-of-the-line sport bike, retaining the CB900F's swoopy tank-sidecovers-tailsection styling, add ing a small sport fairing and new red, white and black paint.

The engine is an air-cooled, acrossthe-frame inline Four with dohc, four valves per cylinder and plain-bearing crankshaft. A link-plate primary chain carries power to an output shaft, which drives the clutch through straight-cut gears. The transmission has five speeds and final drive is 0-ring roller chain.

The biggest engine change is the most obvious: The CB1 100F displaces 1062cc with a bore and stroke of 70 x 69mm, compared with the CB900F's 901cc and bore and stroke of 64.5 x 69mm.

Valve sizes are unchanged, intakes being 26mm and exhausts being 22.5mm, but bigger cam lobes open the valves farther and keep them open longer. The CB1 100F's intake valves open 15° BTDC and close 35° ABDC; exhaust valves open 40° BBDC and close 10° ATDC. The CB900F's valves were timed at 10-35 for intakes and 40-5 for exhaust. Intake and exhaust valves lift 9.0mm, compared to the CB900F's 8.5mm intake lift and 8.0mm exhaust lift.

Maximum ignition advance is still 38.5° BTDC, but the advance curve has been altered to reduce pinging at low rpm. The CB900F reached full advance at 3100 rpm; the CB 11 OOF reaches full advance at 3500 rpm.

Compression is up from 8.8:1 to 9.7:1, and the oil cooler capacity is doubled.

The changes are good for a claimed horsepower increase from 89 bhp to 108 bhp, and the CB1 100F's performance backs up the claims.

At the dragstrip, the CB1 100F's first pass was an 11.31 and the best of five passes made was 11.13 sec. with a termi-> nal speed of 120.48 mph. In the halfmile, the CB1100F reached 141 mph, faster than any other stock bike we’ve tested, a full 12 mph faster than the CB900F tested in May 1981.

CB1100F

More important, the CB1100F performed without hitch. The CB900F had a well-earned reputation for jumping out of third gear when run hard and shifted quickly, a problem that frustrated riders and limited dragstrip times to a best of 11.96 sec. and 110.56 mph in Cycle World testing. Few things are as disconcerting as a bike that jumps out of gear immediately after being power-shifted at redline.

That trait is missing from the CB1100F. To cure the shifting problem, Honda engineers modified the linkage between the shift lever shaft and the transmission shift drum to increase the amount of drum rotation produced by moving the shift lever. That change puts the gears closer together during a shift, actually overshifting, (moving the gears closer together than normal running distance), ensuring that gear dogs fully engage adjacent gears. Production tolerances were also tightened to reduce

the distance between gears in initial transmission set up and shimming.

Other changes in the transmission were made to accommodate the extra horsepower. Better heat treating is applied to several gears and the fifth gear set is wider. The transmission mainshaft hardness is increased to resist wear and gauling.

The clutch is straight out of the CB900F, with eight friction plates and seven steel plates, but has stronger springs. The clutch basket has two thin, spring-loaded gears, one gear with one less tooth than the other, meshing with the output shaft gear. The split-gear design reduces gear noise and backlash. The clutch actuation system still uses a cam and lever mounted in the clutch cover, but now the cam pivot is on the front of the cover and the clutch cannot be adjusted without removing the cover.

A CB900F, ridden hard or run at the dragstrip, would quickly fry its clutch. Despite the stiffer springs, the clutch is still weak in the CB1100F and started grabbing severely after just five dragstrip passes.

But while the clutch isn’t much improved, power delivery is. The CB900F’s peaky powerband required too much rpm for quick departures from stoplights and fast moves through traffic. The 900 lacked the lunge of a good 1100, and, for the size and weight and bulk of the bike, felt underpowered. The extra 161cc and higher compression ratio transform the F powerplant into an example of why people like to ride 1100s. The bike leaves traffic far behind while never exceeding 4000 rpm, or scorches down the highway, accelerating hard while shifted at 6000 or 7000 rpm. Blasts to the 9500 rpm redline eliminate straightaways and dispatch other vehicles with starship effectiveness—just like a GS1100 or GPzllOO.

The CB900F didn’t handle as well as the Suzukis and Kawasakis, even with less power, and adding more power to the engine without changing the chassis would have made the 900F’s wobbling in fast turns worse. So Honda engineers made several chassis changes to improve stability.

Rake was increased from 27.5° to 28.5° and trail went from 4.3 in. to 4.7 in. The steering head tube itself is 28mm longer. The changes have direct connections to Honda’s Superbike racing experience.

Aside from the changes mentioned above, the CB11 OOF’s frame is identical to the CB900F’s frame. There are two main downtubes running from the steering head, under the engine and back to the swing arm pivot area. A section of downtube unbolts just above the right forward engine mount and just ahead of the footpeg to ease engine installation and removal.

Most chain-driven motorcycles with rubber engine mounts have at least one solid mounting point to hold the engine in alignment with the chain. The CB 11 OOF’s engine, like the CB900F’s engine, is completely rubber mounted. To maintain engine alignment with the chain, Honda engineers use two short cast steel link arms running from the forward mounts to the frame. Because these two links bear side-to-side and forwardbackward pressures, their mounting points in the frame must be very strong. So those parts of the frame are cast steel lugs, providing solid fixing points for the link arms. Both ends of the left lug and the bottom of the right lug are welded to the frame tubes. The top of the right lug is split, and the stationary section of frame tube fits into the lug and is clamped by a bolt through one side of the lug.

The CB 11 OOF’s front end is straight off the CB1100R. Like the front end on the 900F, it has 39mm stanchion tubes but uses two bushings in each slider and has a flat, cast-alloy plate-type brace bolted between the sliders, above the fender. Each slider incorporates TRAC anti-dive (a system first seen on the NR500 racebike), which increases compression damping when the front disc brakes are applied. Each caliper is free to pivot on its top hanger, and, when the brakes are applied, swings forward as it grabs the disc. The forward motion pushes the caliper’s lower hanger, which presses a plunger valve and re-routes oil in the compression damping system. The degree of change in damping can be adjusted by turning a screw on the side of each slider to one of four positions.

Rebound damping can be adjusted by turning knobs on top of the fork tubes to one of three positions, and fork air pressure can be varied using one fitting connected to both tubes. The forks are designed to use less air pressure to reduce initial resistance, or stiction, with the recommended pressure ranging from 0 to 8 psi.

Rear shock damping is easily adjusted by turning the shock spring collar cover to one of three positions, and compression damping can be adjusted two ways with a small lever positioned inside the lower shock mount clevis.

The CB11 OOF’s swing arm is made of rectangular steel tubing, painted silver, and Honda claims that the swing arm has 20 percent more torsional rigidity than the round-tube swing arm used on the CB900F. As in the case of the CB900F, the 11 OOF’s swing arm rides on needle roller bearings.

Twin-piston brake calipers are used front and rear, acting on 107/s in. discs in the front and an 11 % in. disc in the rear. The front calipers carry sintered metal pads, which the engineers say don’t affect dry stopping ability but increase wet stopping performance 40 percent and reduce wear 20 percent. The rear pads are still asbestos based, as in the CB900F.

Most disc brake assemblies have two distinct parts, the disc itself and a carrier, which is a cone-shaped piece of metal that bolts to the wheel hub and bridges the space upward and outward to the disc, which is attached to the carrier with either bolts or rivets. The last generation of Honda street bikes featured integral discs and carriers. That is, a stamping machine formed a single flat piece of metal into a disc and carrier, which then bolted to the hub. The Honda carriers had cutout sections, making each carrier lighter and giving it the appearance of having spokes.

The design wasn’t particularly effective; the spokes between the disc surface and the hub were small, lacking rigidity, and couldn’t transfer much heat from the disc to the wheel. It’s also possible that the stamping process introduced pent-up stresses into the metal, stresses which were relieved with the introduction of heat. We’re not certain of the cause, but we are sure of the effect: discs on several Honda models warped when used hard, producing a pulse in the front brake system that could be felt in the handlebar lever.

The CB11 OOF’s brake discs are different. There is no carrier in the normal sense. Instead, the flat discs bolt directly to the cast alloy wheel hub, which is both wider and larger in diameter than a normal wheel hub. This system makes the disc mountin-g more rigid, eliminates stamping-induced stress buildups, and increases heat transfer from disc to wheel. The result should be that the CB11 OOF’s discs do not warp, but it’s too soon to know for certain.

Besides featuring the enlarged hub to which the discs bolt, the 11 OOF’s wheels are unusually wide for a street bike. The front dm is 2.50 in. wide with an 18-in. diameter; the rear rim is 3.00 in. wide with a 17-in. diameter. Both ends carry V-rated low-profile Bridgestone Mag Mopus tires, a 110/90 L303 up front and a 130/90 G508 in the rear.

That the CB1100F has cast wheels at all is a departure for Honda. At one time Honda engineers criticized cast wheels as too rigid, saying that a motorcycle needs a certain amount of wheel flex, and stated that problems with casting porosity made cast wheels unsafe. Honda’s answer was the ComStar, a built-up wheel made of steel (or aluminum) plates bolted and riveted between a special rim and the wheel hub.

Honda’s latest models don’t use ComStars—except for the Turbo, which uses a different type of ComStar—and the official line is that technology has solved casting porosity problems and that cast wheels are now used on Hondas for styling and marketing reasons.

Of course, styling applies to more than wheels. The CB1100F is eye-catching, bright red with white accents and black stripes, with black engine paint and black chrome exhaust pipes and mufflers and a chrome chain guard. The quartzhalogen headlight is rectangular, as are the turn signals, and there’s a new instrument panel mounted above the headlight. The speedometer reads to 150 mph and indicates 60 mph at an actual 56 mph, meaning that it has more numbers > and less accuracy. This is a trade off, and it’s a shame that when the NHTSA rescinded the decree that mandated 85mph speedometers, the close-tolerance accuracy required by the same decree was lost.

The handlebars are an interesting mix, tubular steel bars fitting into cast steel risers which are in turn held by conventional handlebar clamps on top of the upper triple clamp. The cast steel risers can be pivoted forward or rearward in the handlebar clamps, and the tubular steel bars can be pivoted inward or outward in the cast steel risers, making the bars adjustable in several directions. The top of the triple clamp and a fuse box are hidden by a plastic cover which extends up to the instrument panel.

It might seem reasonable to assume, that all these changes and improvements and progress might be paid for in the addition of weight, but that’s not the case. Ready to roll with half a tank of fuel, the, CB1100F is one pound lighter on Cycle World's certified scales than the CB900F, 567 lb. to 568. That’s still more than competing superbikes, but the Honda’s prodigious power output makes it dead even in performance despite the extra weight.

It might also seem reasonable to assume that the huge influx of power might make the CB1100F less well-suited for in-town use or sedate riding but once again, that’s not the case. The 1100’s flat torque curve invites chugging around town, and the spark advance curvemeans it doesn’t detonate and ping badly at low rpm as the CB900F did. The only casualty to big bore and big power is the engine vibration level: below 4000 rpm-1 the 1100 vibrates enough to be intrusive, as if the rubber mounts weren’t designed to absorb the specific vibration pitch pro-. duced at low engine speed. A little above/ 4000 rpm, however, vibration disappears.

Making horsepower isn’t the only, thing the Honda does well. Remember the sintered metal brake pads said to stop as well in the dry and better in the wet? We didn’t have a chance to try the’ CB1100F in wet conditions, but the numbers from our (dry) brake tests show the CB1100F stopping as well as the CB900F, both taking 30 ft. to stop from 30 mph, the CB1100F taking 130 ft. to stop from 60, the CB900F taking 129 ft. to stop from 60 mph.

Remember the frame changes? There isn’t a more stable bike. Dial up the Honda’s damping to full all around, jack up the fork pressure to 8.0 psi and shock spring preload to number three position or higher and set out for the meanest, roughest, fastest sweeper you can find. The wobble is gone.

Some of that stability must relate to the frame geometry, but perhaps the wheels deserve some credit, too. At least one tire company, plagued by stability problems (wobbles) while testing at high speed with a CB900F, cured the problem by removing the stock ComStars and installing cast wheels. The wider rim sizes have also helped the CB1100F.

No matter. What does matter is that the Honda CB1100F is a high-performance match for any 1100, in terms of speed and acceleration and handling and braking ability, and has superior cornering clearance as well.

Factor in the comparatively low price of $3698 and the Honda CB1100F demands the attention of anybody in the market for a serious high-performance motorcycle. S

HONDA CB100F

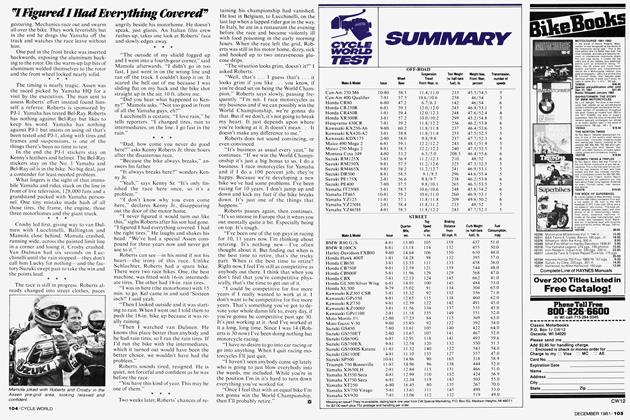

SPECIFICATIONS

$3698

ACCELERATION

PERFORMANCE